Editor’s note: This blog post was first published by Partnership Schools.

As the adage goes, “defense travels.” The idea is that, no matter how high-powered, a team’s offense is more likely to falter in a road game than a well-practiced defense. And so coaches who focus on building strong defense can more reliably prepare players for the rigors of a road game.

The same could be said for English language arts lessons in this period of remote learning: When forced to take our show on the road, it is reading that travels because it prepares our students to be independent learners. The supports present in the classroom, even things as simple as being able to watch a student’s reaction to reading a text, that allow teachers to play offense during instruction largely have been taken away. While teachers and students have adapted elements of physical classrooms to synchronous online ELA lessons, our students are still more on their own than they were before the pandemic.

The reality of this situation means that our ELA “road game” rests on how effectively we’ve helped students learn content and develop habits they need to make meaning from complex texts independently. And as we consider the most important instructional lessons of the COVID era, one is that, when we have the advantage of in-school instruction, we should focus our reading lessons on three key moves that help build strong reading comprehension. They are:

- Immerse students in a rigorous, coherent, knowledge-building curriculum.

- Help students understand and focus on the affordances of a text.

- Help students unlock the power of background knowledge as they read.

First and most importantly, we believe that a student’s ability to understand complex text depends largely on whether s/he has built a store of knowledge that provides the context and content background s/he’ll need to make sense of the text.

At Partnership Schools, our upper elementary and middle school ELA road game was made stronger by the fact that our students are immersed in knowledge-building curricula beginning in pre-K. They learn about history, science, literature, and the arts. And so, as they work to read independently during the remote lessons that coronavirus now demands, they have a wealth of background knowledge that provides the context they need to understand grade-appropriate texts.

However, learning facts and figures is just the tip of the iceberg. The heart of our instructional focus in fourth through eighth grade is helping our students make the most of the knowledge they have built by using it to make sense of new texts that have new ideas.

Kat Prevo, a fourth grade teacher from Our Lady Queen of Angels in Harlem, is testament to this approach. In her first year of teaching she has set up her students to be independent readers.

The key to Kat’s reading lessons is that the text is the anchor for building knowledge. She does not start a lesson from a unit on the American Revolution about the burgeoning discontent in Massachusetts in the 1760s by telling her students why the colonists were frustrated with Parliament. They have to figure out the author’s view on the subject by reading the text.

But just assigning fourth graders a chapter to read is not teaching. Kat helps students become independent readers by supporting them in two ways as they read to learn content:

One, help students understand and focus on the affordances of a text. In Timothy Shanahan’s words, an affordance of a text is “any resource or support the text offers to readers that can help to facilitate communication or understanding.” Independent readers need to be able to identify and use the affordances of a text to make meaning from it. In her classroom, Kat often gives students a chance to catch affordances independently. If they miss an important one, she asks them about it. If they are still confused, she is ready to provide an explanation of its meaning so that they might be more likely to catch a similar affordance next time.

While Kat is always there to provide support in the classroom, her students are socialized to look for help in the text first. When students transitioned to distance learning, they were prepared to use the affordances the author provides them to help figure out the meaning of a text.

Two, help students unlock the power of background knowledge as they read. Kat teaches students to use their background knowledge to help make sense of a text. In the classroom, this takes the form of retrieval practice before the day’s reading or a scaffolding question about relevant information they have studied when a text trips them up.

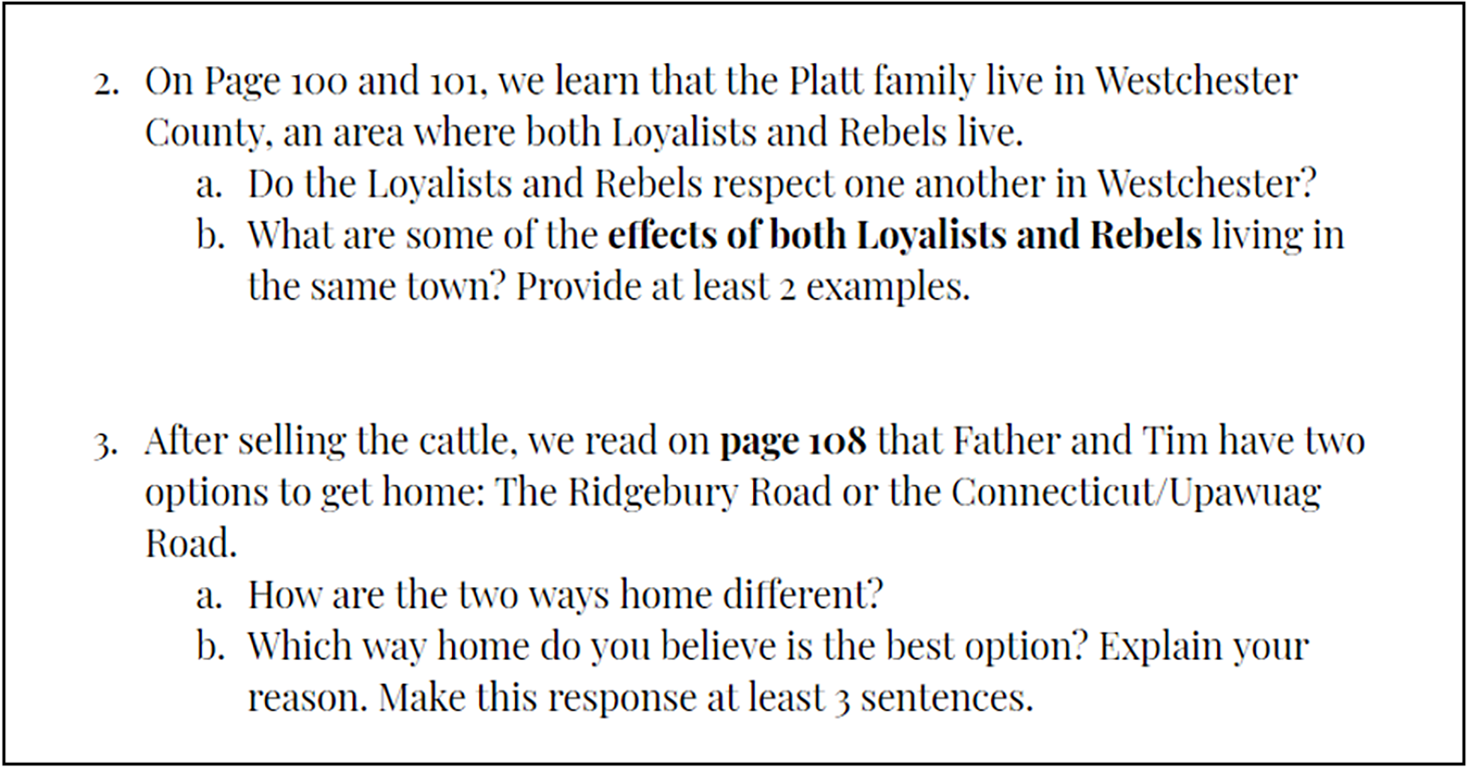

Kat adapted these instructional moves to distance learning when her students read My Brother Sam is Dead. She used questions to support comprehension by directing her students’ attention to vocabulary and ideas that they would recognize from their recent study of the American Revolution. For example, in the following two questions from Kat’s teaching materials, she asks students to use what they know about Patriots and Loyalists to help them understand the effects that politics of New England towns in the 1770s have on the characters:

Kat’s instruction throughout the year made her students better readers, which prepared them to be more independent learners. When they read My Brother Sam is Dead at home, they learned about the perils of choosing sides during the overthrow of a government, which they will be able to draw on when they study the French and Haitian Revolutions in sixth grade. When they are reading independently, they are considering ideas that are transferable and transformative, which seems like a worthwhile goal no matter where students are learning.

During the first six months of this school year, we may not have realized we were preparing for a “road game.” But we’re realizing now more than ever that students’ ability to grapple with rigorous work independently—so essential right now—is built by teacher providing frequent “workouts” of finding affordances, tapping into background knowledge, and doing so with coherent, knowledge-building curricula—whether that practice happens in class or at a distance.