Last month, I had the good fortune to travel to Santiago, Chile, to speak at a fantastic education conference organized by a leading think tank (LYD) and university (UDD). I was the latest in a long line of education policy wonks to make the trek to this annual event, including Eric Hanushek, Harry Patrinos, Steven Rivkin, and Paul Peterson.

In line with the old cliché about travel, while there I learned as much about America’s education system as I did about Chile’s. The most important lesson was that our recent achievement declines—much discussed at August’s Republican debate, and which, as gauged by test score trends, started almost a decade before Covid struck—are far from unique.

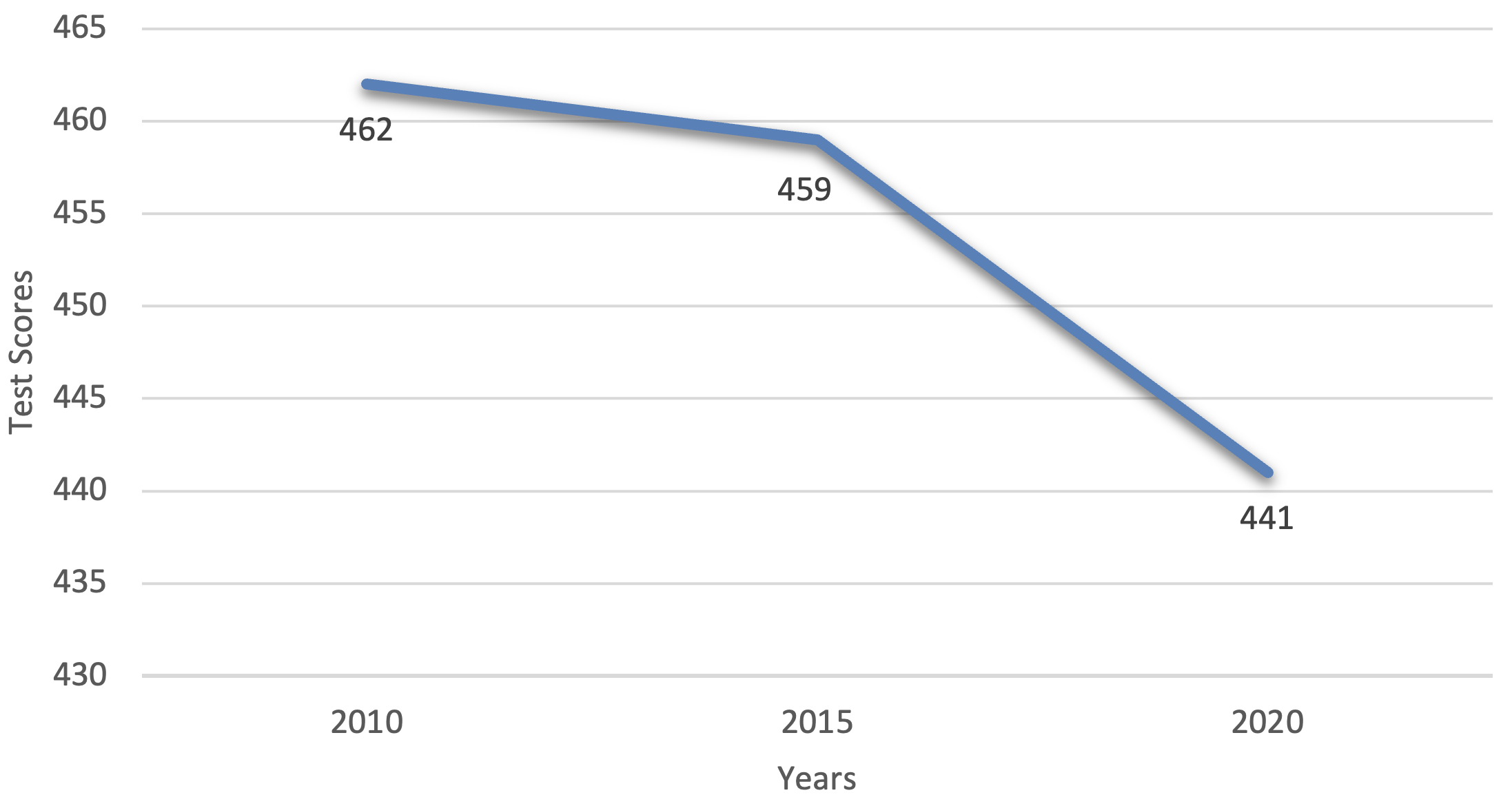

Chile’s academic progress, as measured by international assessments, also stalled out in the early to mid-2010s, just like ours did. Note, for example, their downward trends in fourth grade math on the Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS).

Figure 1: Chile’s fourth grade math average scores on TIMSS, 2011–19

Chilean schools also face a teenage mental health crisis, much like we do, as well as rising violence and disorder in and around their campuses.

The mental health trends did not surprise me, given the important work that Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge, among others, have done to track the rise of teenage anxiety and depression around the globe and their potential connection to the widespread adoption of smartphones and social media starting around 2012.

But achievement, too? That made me curious. Were other also countries seeing a similar slowdown or decline in test scores in the pre-pandemic years?

Getting a straight answer to that question is hard, as there’s no “global achievement trend” to point to. That’s because, even with the growth and durability of international assessments such as TIMSS, PISA, and PIRLS, there’s not a large and stable group of countries that have taken the same tests over a long period of time. Four scholars (Noam Angrist, Harry Patrinos, Simeon Djankov, and Pinelopi Goldberg) tried to overcome this challenge in an important article published by Education Next last year by linking international exams to those given regionally. Their result was plenty sobering: There’s little evidence of learning gains worldwide from 2000 to 2015.

Another approach is to select a group of nations and examine their own trend lines. But which countries would serve as the most appropriate comparison? Seems to me that the G7, representing the world’s large, advanced democracies, is as good as any. That means Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the United Kingdom, as well as the U.S. We’ll substitute Ontario for Canada and England for the U.K., as these jurisdictions have participated in international exams for much longer. Sadly, France’s and Germany’s participation has been spotty.

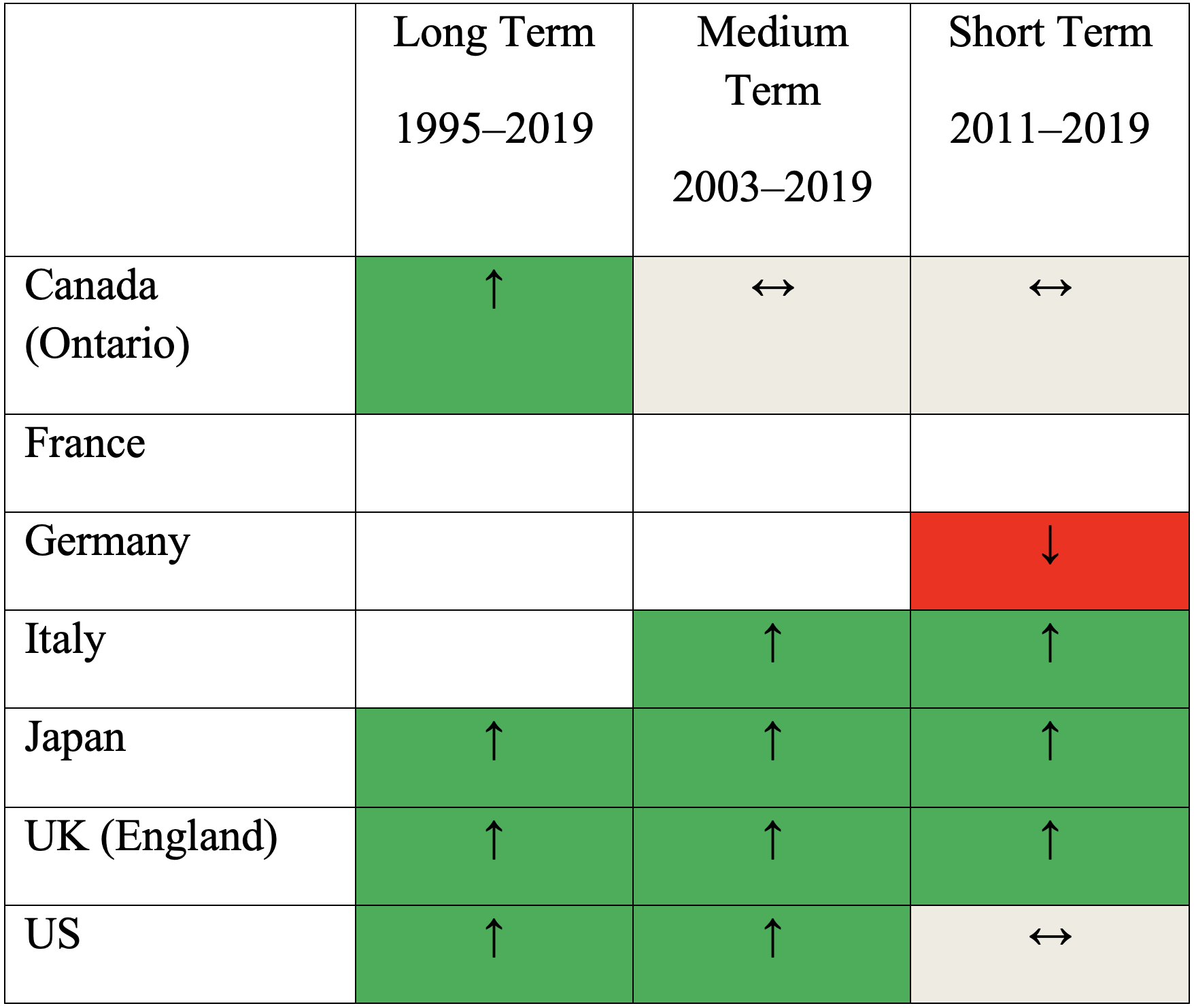

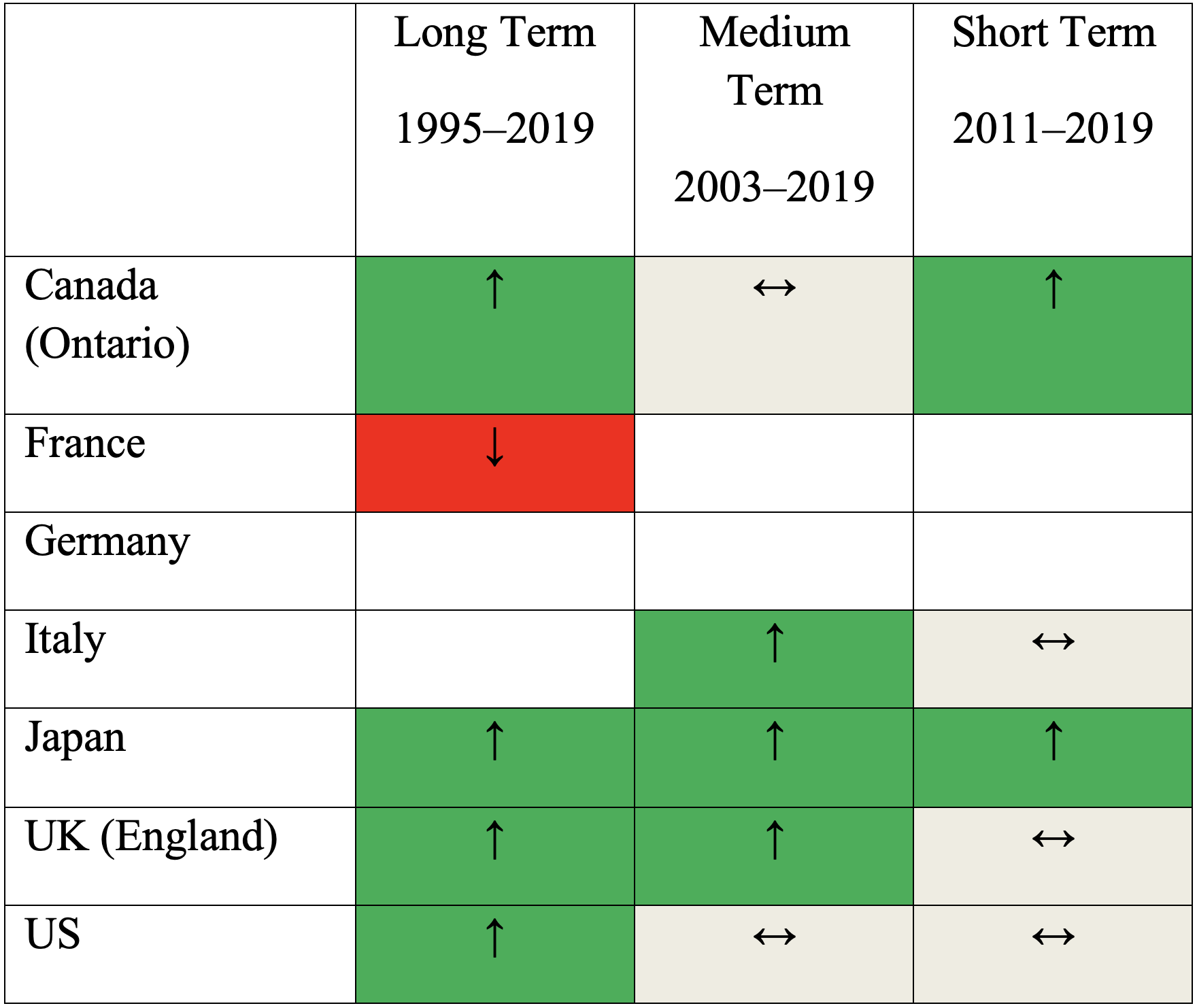

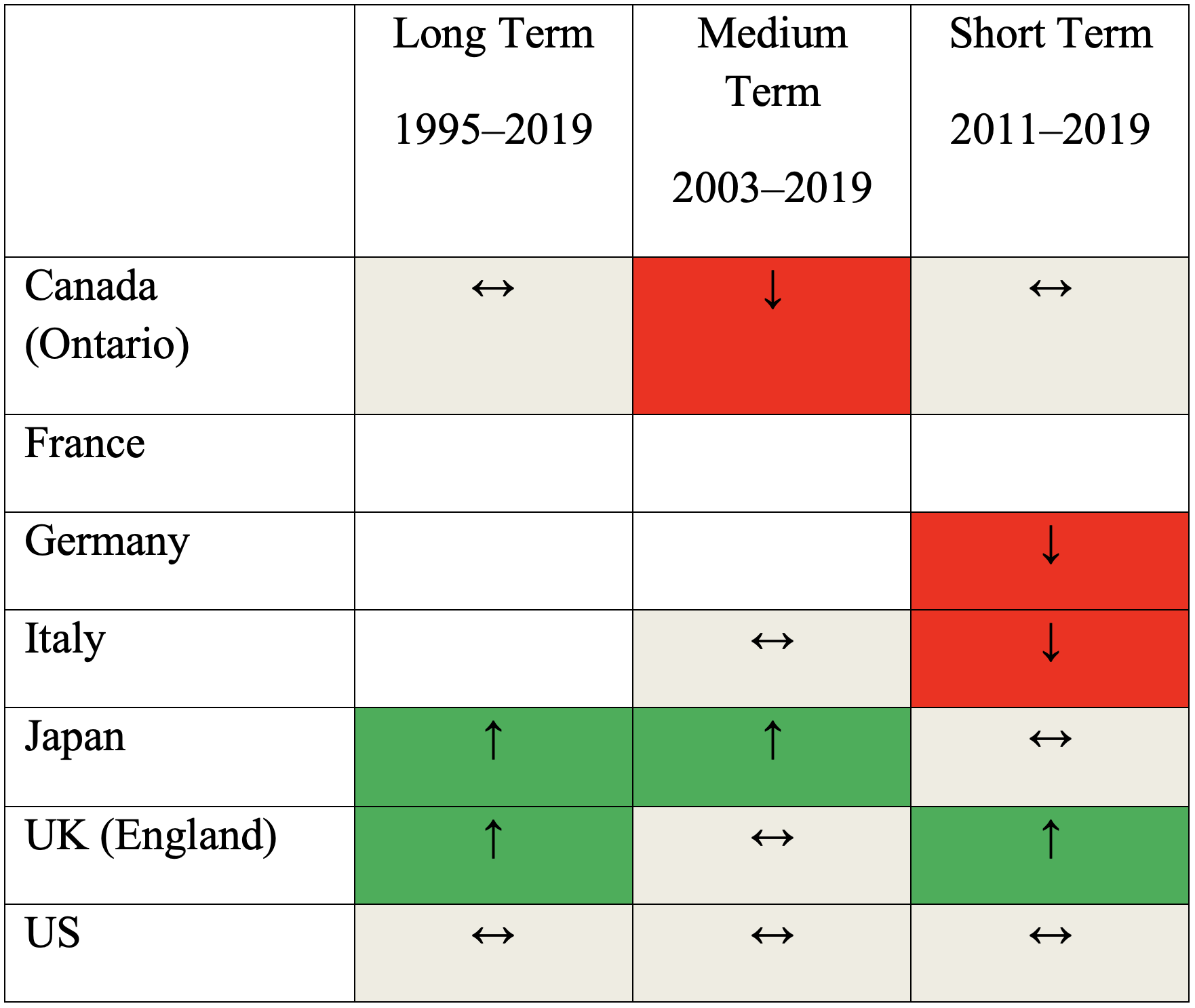

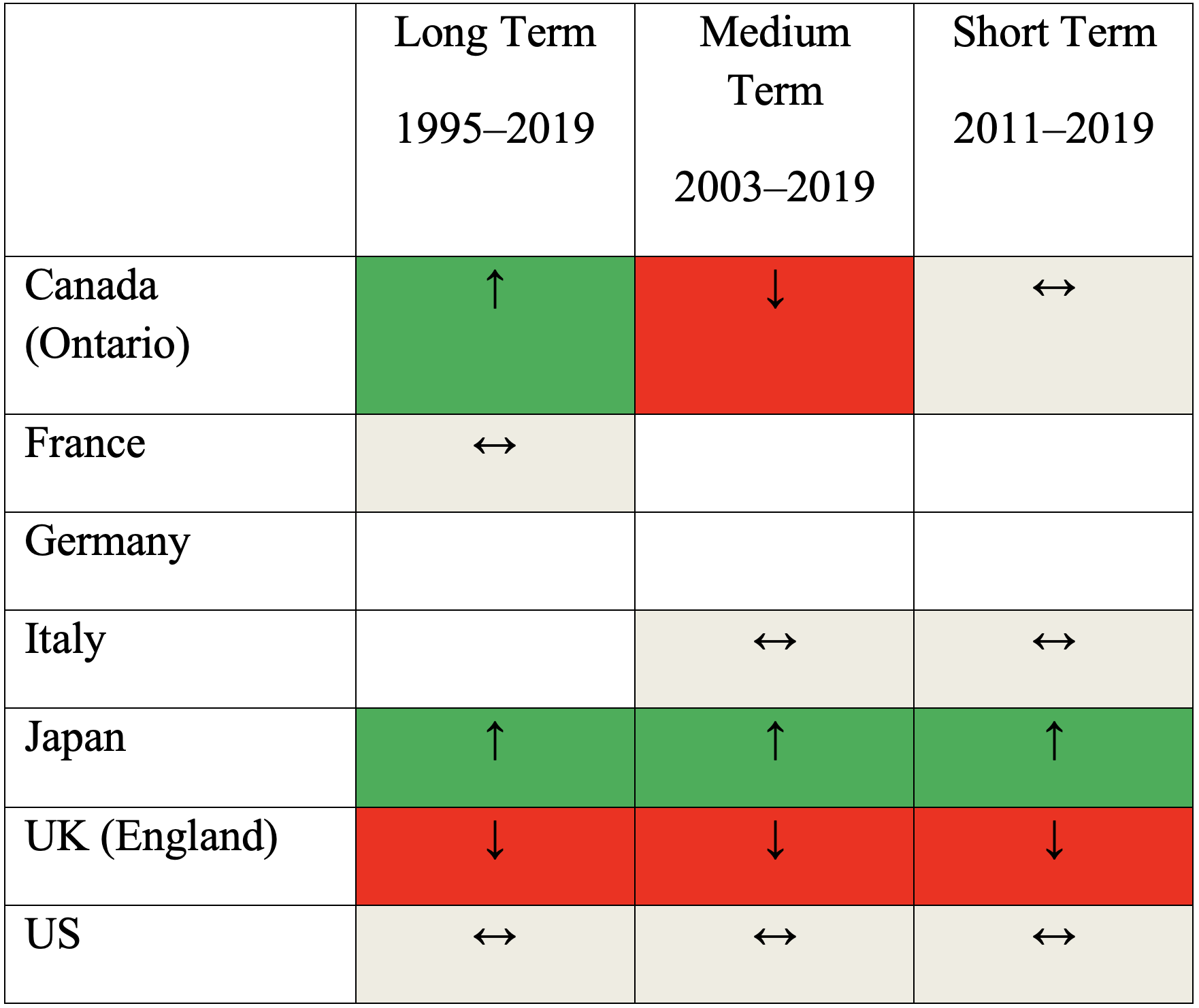

Let’s take a look at the long-, medium-, and short-term trends on TIMSS—which people I trust view as more reliable than PISA—for the G7 nations.

Table 1: TIMSS fourth grade math trends for the G7 nations

Table 2: TIMSS eighth grade math trends for the G7 nations

Table 3: TIMSS fourth grade science trends for the G7 nations

Table 4: TIMSS eighth grade science trends for the G7 nations

To be honest, I’m not seeing many, if any, patterns here. Perhaps, if you squint, you can spot a more negative story, in general, for the most recent period, with trends more likely to turn flat or down. (America’s have turned flat, though we see actual declines in some NAEP data.)

It’s also possible to find other countries whose trajectories look similar to ours. Most notably Canada (represented here by Ontario), whose better days, like America’s, tended to be back in the late 1990s or early to mid-2000s. We don’t have much data for Germany, but it has struggled of late, too.

But Italy, England, and especially Japan have demonstrated a striking ability, in most grades and subjects, to continue to make progress, all the way through 2019. (We’ll get post-pandemic scores—for 2022—soon.)

So the most straightforward take is that it’s a mixed bag.

What to make of these “null” findings? In my view, they provide important context for our understanding of America’s achievement trends. There’s been a vigorous debate, on social media at least, about why our achievement gains stalled out in the early to mid-2010s. (As another recent analysis of TIMSS demonstrated, that stalling out was driven by declines for our lowest-achieving students. A widening gap between America’s low and high achievers in the 2010s is a consistent finding across international exams and NAEP.) Sandy Kress, one of the architects of No Child Left Behind, argues that it’s because we stopped enforcing that law and gave up on holding schools accountable. It’s not a crazy notion, for the timing lines up quite well and we really did stop threatening schools with takeovers and shut downs around that time.

Building off the research of Kirabo Jackson, among others, I’ve pointed to a different culprit. Namely, the Great Recession, which threw millions of children into poverty, and in America, at least, led to significant cuts in education spending, especially in the very schools where we saw the greatest achievement declines.

But the Great Recession was a worldwide phenomenon, so why didn’t it have a similarly destructive impact on other systems around the globe? How did England and Japan, in particular, weather the storm so well? Was it their more robust social safety nets or school funding systems? Or is the Great Recession a red herring?

And what about those darn smartphones? I’ve wondered lately whether they could be curtailing student learning in addition to harming kids’ mental health. It’s not hard to imagine that increased screen time, in combination with dopamine-releasing social media apps, could negatively impact attention, sleep, and so much else that’s critical to success in school. But again, smartphones are ubiquitous across the G7, too, and there’s no sign that students in, say, Japan are being handicapped by them.

In a way, it’s a relief to know that America’s achievement woes aren’t in lock-step with broader trends from around the world. It means that our (pre-pandemic) declines were the result of something that we were doing (or not). And that means we alone can fix it.