The tremor that you felt last week was the dropping of a new Emily Hanford radio documentary, “What the Words Say: Many kids struggle with reading—and children of color are far less likely to get the help they need.” Since she started reporting on reading several years ago, Hanford has kept up the pressure on the scourge of educational malpractice that is America’s approach to reading instruction. Her formula is simple but effective: gut-wrenching stories interwoven with science, data, and a just-the-facts-ma’am ethos.

Clocking in at just under fifty-three minutes, Hanford’s latest entry hones in on how early reading problems are particularly acute with Black, Hispanic, and Native American students. Unlike White and Asian children who often have more opportunities to develop E.D. Hirsch’s concept of cultural literacy at home, low-income children of color often attend schools that fall short in building content knowledge, vocabulary, and reading comprehension, a failure from which they rarely fully recover.

Hanford’s first documentary on reading, now three years old, explored how poorly kids with dyslexia are being served. Her next two tackled the broader problem of reading instruction failure, stemming from misbegotten strategies and schools’ refusal to teach decoding. This time, Hanford delves deep into the importance of building knowledge and vocabulary so kids can understand the words they decode—lest they start the path toward dropping out of school and being consigned to the criminal justice system.

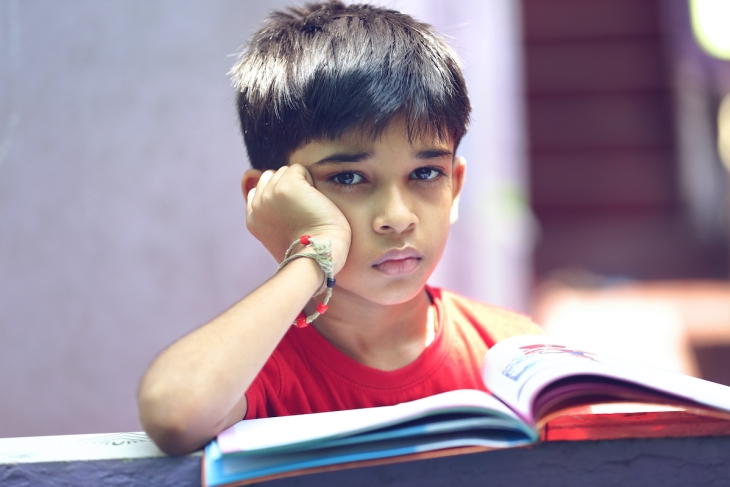

Indeed, in a windowless cinderblock room at a juvenile detention facility in Houston, Hanford sat in on a cringeworthy reading lesson with a fifteen-year-old that had been failed by his teachers and his schools:

He was trying to read a story about a man taking a bus ride. Occasionally, he’d successfully sound out and there’d be a flash of recognition. “Woman!” he exclaimed after slowly decoding the word. But it was clear from earlier in the lesson that Mateo didn’t know the meaning of a lot of the words he was trying to say: fleet, sneer, gloat. If someone had read the story out loud to him, he wouldn’t have understood it all.

Listening to Mateo struggle and labor through the words was as painful as it was heartbreaking, to think what might have been had he been explicitly taught how to decode words earlier in his life. Rather than entering the downward spiral that locked him into purgatory as a beginning reader into his teens, he would have been lifted up by the virtuous cycle created when young children, fluent in decoding, recognize words they haven’t seen but have heard many times.

My daughter, who will be entering kindergarten in a couple of weeks, is a prime example of the Matthew Effect described by reading researchers and underscored by Hanford in her piece. Before ever setting foot inside her new school, she’s already reading at a fourth-grade level, and is particularly voracious when it comes to anything written by Mo Willems, Dav Pilkey, or Aaron Blabey. I’ve been paying close attention to her language comprehension by chatting with her on all sorts of topics and exposing her to a bounty of experiences outside of school to build her background knowledge, which is the whole ballgame when it comes to being literate.

Of course, the effort I’ve invested in my daughter’s reading stems from an abiding love, but it also comes after years spent in schools and recognizing that I needed to obtain an insurance policy against the risk of her becoming a struggling reader. As Hanford soberly observes, America’s schools reflexively believe one of two things when a child stumbles. One, there must be a problem at home (he wasn’t read to enough), or two, there must be a problem with the child (he has a learning disability). It seldom occurs to schools to hold up the mirror and admit they never taught the child how to read.

Honesty and responsibility on the part of schools would have made all the difference for Sonya Thomas, a Nashville mother profiled by Hanford, whose pleas to address the reading problems of her son, C.J., went unanswered until he reached the seventh grade, when she learned that he was only reading at a second-grade level. Left to slip through the cracks, the overdue revelation brought Thomas to tears, as it surely does for millions of parents like her who place their faith in schools to ensure their children master the most basic and most fundamental academic skill. Infuriated, Thomas is now a woman on a mission to help families avoid the grotesque dereliction of duty on the part of those charged with the education and care of C.J., Mateo, and countless children now staring down the barrel of a needlessly difficult life as an adult.

In the wake of national unrest and a renewed demand for racial justice, and on the eve of a back-to-school season unlike any in memory, Hanford’s newest offering is timely because it travels upstream to remind us why these deep-seated inequalities among U.S. children continue to persist. On national reading tests, more than 80 percent of Black and Native American students score below proficient, and 77 percent of Hispanic students remain mired under that same threshold. Making matters worse, many parents don’t know how far behind their kids are until it’s too late.

As inexcusable as this state of affairs may be, it’s unclear how things are supposed to improve in the time of Covid-19. If Hanford makes one thing palpable through her reporting, it’s that schools have a hard enough of a time teaching children how to read when the lessons are conducted in-person, let alone through the keyhole of Zoom. With many schools planning to remain physically shuttered through at least the first semester, if not longer, they would do well to leverage the wealth of resources available to bridge the gap. If they don’t, the Matthew Effect on reading comprehension will take hold and never let go.