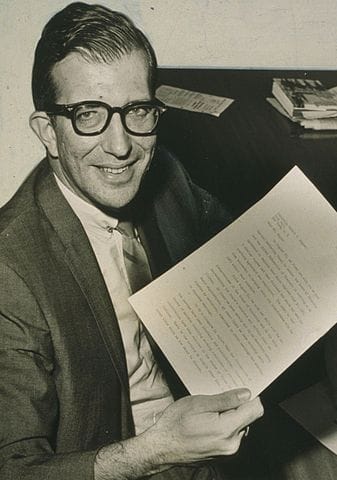

The late AFT president Albert Shanker was instrumental in creating the NBPT. Photo from the Library of Congress.. |

As President of the AFT, the late Albert Shanker was instrumental in creating the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS) and much else in the education-reform world. Now Randi Weingarten is trying—earnestly and imaginatively—to return the organization and its (present) leader to the pantheon of real reformers.

Their new and much-ballyhooed proposal, contained in a report titled Raising the Bar, revives the Shanker-era idea of a “bar exam” for entering teachers—and charges the NBPTS with putting it into practice.

Andy Rotherham came out within hours with multiple doubts, some of which worry me, too. But let’s start by crediting Ms. Weingarten and her organization with a serious proposal to raise standards for new teachers as part of a broader effort to strengthen the profession.

Their proposal has three pillars. The second—but most important so far as I’m concerned— is this:

Teaching, like other respected professions, must have a universal assessment process for entry that includes rigorous preparation centered on clinical practice as well as theory, an in-depth test of subject and pedagogical knowledge, and a comprehensive teacher performance assessment.

My eye went immediately to the phrase “in-depth test of subject…knowledge,” and I combed the rest of the document seeking more on that topic—only to be dismayed by how little is actually said on the matter, other than that the NBPTS is supposed to figure it out. There is no hint of what in-depth knowledge might mean for a U.S. history teacher versus a geometry teacher versus an art teacher, nor does it address what sort of testing arrangement might gauge whether an individual possesses enough of it. (We know that the current arrangement—with most states relying heavily on the “Praxis II” test—does not do this well. We also know that some states do not take this issue on at all.)

The devil lurks prominently in details that are yet to be developed, not in the impulse to raise entry standards for teachers.

The other two pillars, I have to admit, gave me pause. The first says “all stakeholders must collaborate”—a recipe for stasis and mediocrity if I’ve ever seen one. And the third assigns “primary responsibility for setting and enforcing the standards of the profession” to “members of the profession—practicing professionals in K–12 and higher education.” In other words, elected officials, employers, taxpayers, and parents can jolly well butt out; the standards governing classroom entry are none of their business. (I guess that’s true for think-tankers, too.)

Back to the “universal assessment”: I can easily understand why the AFT is giving that assignment to the NBPTS, but I’m not sure that organization is up to it—particularly the “knowledge” part. They administer very elaborate and expensive appraisals of teaching practice to veteran classroom practitioners, but I’ve never seen the National Board show much interest in subject-matter knowledge. Pedagogy, yes. Even lesson-planning. But not the causes and consequences of the Civil War or the ways that atoms combine to form molecules. Indeed, I’ve seen scant evidence that the powers-that-be at NBPTS even care much about such mundane stuff as content knowledge. (This part of the job, at least for grades K–8, should have been assigned to the Core Knowledge Foundation).

All of which is to say, the devil lurks prominently in details that are yet to be developed, not in the impulse to raise entry standards for teachers. (Unsurprisingly, this union-developed proposal deals only with new teachers, not with whether veteran instructors need to meet any standards of any sort.)

The Rotherham critique includes four more notable points.

- Is the AFT plan—billed as “leveling the playing field”—really just a sneak attack on Teach for America and other “alternative” routes into a fast-decentralizing profession? Excellent question.

- “What if we don’t know as much as we like to presuppose?” In a few subjects and grade levels, there is bona fide research-based knowledge and best-practice tradecraft. But “what truly makes a great 10th grade English teacher or 12th grade government teacher?” asks Andy. Another solid question.

- “For state policymakers, how demanding teacher tests are is as much, often more, a labor-market issue than it is an educational one.” A legitimate concern, indeed. It’s far easier to find (and pay for) a top-notch algebra teacher to fill an opening in Boston or Austin than in the Mississippi delta or rural Idaho. That’s why states have long been free to determine their own certification norms and Praxis passing scores. Can a field this big and diverse truly accommodate a single “high bar”? (This is so for other fields, too, which is why it’s easier for newly minted attorneys to pass the bar exams of some states than others.)

- Finally, and perhaps most fundamentally, what if “education isn’t really like law or medicine,” but more like business or journalism (or think-tankery), where “credentials are valued but weighted alongside other factors because there isn’t a field-wide core of knowledge or skills all practitioners must have?” Rotherham is not entirely correct on this one, however. Law and medicine do have “field-wide” cores of knowledge but only up to a point. Intellectual-property lawyers and personal-injury ambulance chasers don’t have a whole lot in common, nor do ophthalmologists and gastro-enterologists.

Some of these are unanswerable within the framework of the AFT proposal and the NBPTS, the more so once it rounds up “all stakeholders.” But let’s not doom this baby at birth. Let’s welcome its arrival, wish it good health, cross our fingers (maybe even help if asked), and stand by ’til it can walk by itself. Thanks, Randi, for a proposal that would make Al proud—and that could conceivably do American education some good. Or could just as easily create nothing except false hope and, possibly, some damage.