Way back in the pre-pandemic Before Times, one of America’s more consistent and pernicious long-term trends was the growing domination of so-called “superstar cities.” As Richard Florida explained it, a winner-take-all dynamic was allowing a handful of metropolitan areas to dominate the knowledge economy. San Francisco and Silicon Valley, Washington, D.C., New York City, Boston, Austin, Miami, the Research Triangle, and a handful of other leading metros were raking in jobs, venture capital, highly educated workers, and the various benefits (and occasional challenges) that come with those attributes. The rest of America’s cities, not to mention its small towns and rural communities, were increasingly being left behind.

The contest to choose a new Amazon headquarters was symbolic of this frenzy, with hundreds of locales begging the retail giant to pick them, complete with promises of tax breaks and other incentives. Then they watched Jeff Bezos choose the D.C. area and New York City—winners taking all, yet again. (New York later backed out, under pressure from progressives, and Nashville got something of a consolation prize.)

Bezos et al. faced plenty of criticism for giving hope to the underdog cities and making them cough up data that Amazon could exploit for other purposes. Yet it was hard to fault their final decision. As the Brookings Institution’s Alan Berube wrote, it was all about “talent, talent, talent.”

There’s little doubt that the New Yorks, Bostons, D.C.’s, and Silicon Valleys are very effective at attracting talented and highly educated workers. In a virtuous cycle, these individuals migrate to where the highly paid jobs are, where lots of other smart young people live, and where all manner of amenities make their nonworking life more fun. But workers are also drawn by the promise that their own children, whether extant or prospective, will enjoy high-quality public schools in their new home towns.

But is that actually true? Do the “superstar cities” boast better public schools than those in the Rust Belt or Sun Belt? Business leaders often say the quality of local schools is a key factor when choosing new locations for corporate headquarters or facilities. But are they looking at the right data when judging school quality?

Label us skeptics

Longtime followers of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute won’t be surprised to learn that we are skeptical of how school success tends to be measured. It’s not the fault of the business leaders—or even the economic development folks who strive to woo them. It’s simply a fact of data availability and access. Until recently, few sources allowed nationwide comparisons of schools below the state level. And those sources that did exist, such as average SAT scores or graduation rates, are terrible at helping us understand the quality of the schools. That’s because such “status measures”—snapshots of performance—are so closely related to the demographics of individual schools and districts. It’s why, for so long, communities that have touted their “great public schools” were actually just bragging about schools populated by the children of highly educated parents.

That’s a lousy definition of school quality because it doesn’t consider whether schools are actually effective at helping students learn. It allows the schools in upper-middle-class suburbs to rest on their laurels, while hiding the amazing work done at many high-poverty schools, whose students start out way behind but may make remarkable progress year to year—even if they never quite catch up to the more advantaged kids. Not every high-poverty school pulls that off, not by a long shot, but more succeed at it than you might think, certainly more than city-comparers have been able to see.

So in Fordham's new report, America’s Best and Worst Metro Areas for School Quality, we wondered: If we could measure school effectiveness the right way, by looking at student progress over time, would a different picture of school quality emerge? And in particular, could we start to determine at the metro-area level which American regions really have the best—i.e., the most effective—schools? Might such an analysis assist business leaders in giving more metros another look when making locational decisions—especially in the post-pandemic world, now that so many workers are rethinking their commitments to “superstar cities” with their sky-high housing prices, soul-grinding traffic, and distance from family?

As for the challenge of usable data, that one has been solved, thanks to the impressive Stanford Education Data Archive (SEDA). Leveraging state summative assessments and adjusting them for states’ performance on NAEP, the analysts at SEDA have enabled previously impossible comparisons of schools, districts, and cities across the land.

Equipped with these excellent data, we set out to build valid comparisons at the metro-area level for school quality across the United States, complete with an interactive website. We are grateful that our friends and colleagues at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation agreed to join us in this pursuit. The Chamber’s affiliates are key players in economic development decisions, active in recruiting employers to their regions. They are integrally involved in local education issues, too, as major funders and consumers of the education system. Readers may also remember that the Chamber has a long history of educational rankings, going back to its excellent Leaders and Laggards series. We greatly appreciate the Chamber’s support and involvement.

We’re also deeply grateful to external reviewers Kristin Blagg, senior research associate at the Urban Institute, and Stephen Holt, assistant professor of economics at SUNY Albany, for offering advice on the rankings methodology and reviewing the interactive website; to Fordham’s associate director of research Adam Tyner for serving as lead analyst, project manager, and number-cruncher; and to Juan Thomassie for designing the interactive website.

Introducing the SLAM rankings

Because we thrive on catchy acronyms, we’re calling these rankings the Student Learning Accelerating Metros, or SLAM. The measures that go into these rankings are those most clearly connected to school effectiveness and that are available nationally at the school district level—namely:

- Academic growth (worth 60 percent of the score in our preferred ranking system).

- Academic growth for traditionally disadvantaged students (worth 20 percent).

- Improvement in achievement in recent years (worth 10 percent).

- High school graduation rates (worth 10 percent).

All these measures are adjusted for demographic differences in districts’ pupil populations.

What’s different about the SLAM rankings compared with other measures of school quality is that they correlate far less with family wealth and student background than do simple academic achievement ratings. They are heavily weighted toward student progress because schools have more control over how much their students grow during the K–12 years than they do over, say, the percentage of residents with a doctorate degree (which other rankings use).

So enough with the preliminaries. Let’s look at the results.

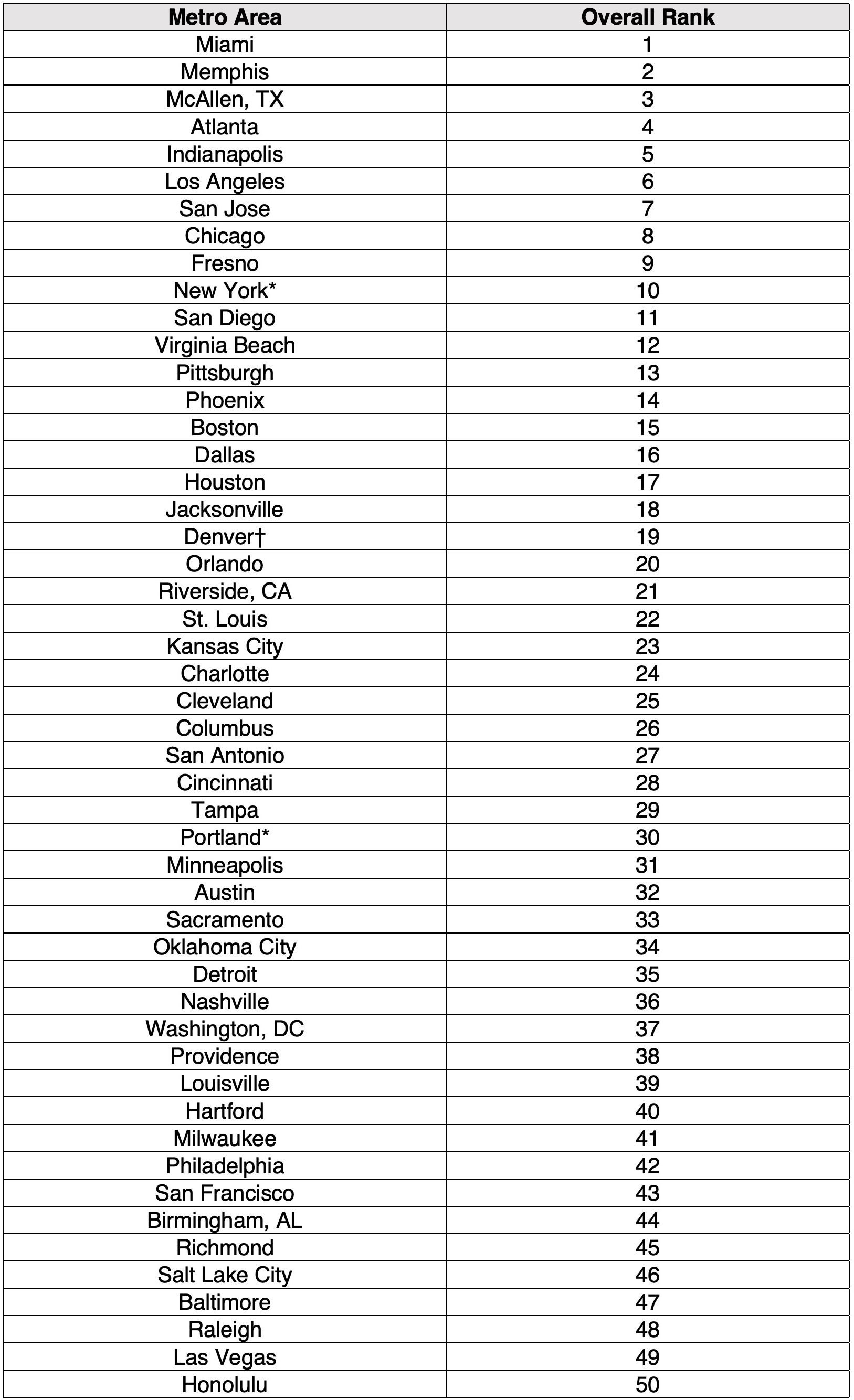

Table 1. America’s fifty largest metro areas ranked by school quality

Note: Each metro represents a core-based statistical area that includes nearby suburbs, towns, and other cities. Metro area names are abbreviated for legibility; full names appear in the report’s Appendix. All outcomes are adjusted for district-level demographics.

*Metro is missing data for its largest district for all recent observations, meaning New York City Public Schools and Portland Public Schools.

†Key data points are missing in the early years of the SEDA data. Because missing early data makes it impossible to calculate metro progress, the value for that variable is imputed to align with the metro’s performance on the other components of the SLAM ranking.

What should be clear is that some superstar cities do better than others. The Miami metro area—South Florida really, including Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties—comes out as number one. The “capital of Latin America” has been on a tear of late, increasingly attracting venture capital and corporate headquarters, especially in the finance industry. New arrivals will find excellent schools for their kids.

The Boston metro area does quite well, too. To be sure, it’s affluent and well educated, which is not surprising, given the presence of so many world-class universities, medical centers, and tech companies. But schools there aren’t standing still. Students are making significant progress over time, as well, along with students in the Los Angeles, San Jose, and Chicago metro areas.

Yet that’s not so in some superstar cities. The San Francisco metro area looks pretty bad, once we measure school effectiveness the correct way. The Washington, D.C., metro area is not much better. Or look at Raleigh, in the Research Triangle, which is way down on the list.

Be careful, too, not to confuse metro areas with their central cities. For example, Washington, D.C., itself shines on our ranking, thanks to its rapidly improving public school system and its highly effective charter school sector. The Northern Virginia suburbs of Fairfax and Loudoun County, however, are dragging the metro down. They are rich and highly educated, but their pupils don’t appear to be making much progress from year to year. Indeed, Amazon may have erred in placing its new headquarters in Northern Virginia instead of, say, Maryland’s Prince George’s County, which is less affluent and much more diverse but boasts schools that are helping kids make more progress, especially once we control for demographics.

Meanwhile, some other large metro areas deserve a fresh look, given the quality of their public schools, including Atlanta, Indianapolis, and Fresno. The rankings for Memphis, Tennessee, and McAllen, Texas stand out in particular, with remarkably effective schools despite their Deep South and Border Town poverty—likewise, the mid-sized metros of Jackson, Mississippi, and Brownsville, Texas. Other mid-sized cities deserve attention, too, including Sarasota, El Paso, Boise, and Grand Rapids. (See the full results for mid-sized metros in Table A3 in the report’s Appendix.)

—

Great public schools are essential to the health of any community. They’re a powerful driver of economic development. But we need to make sure we’re defining “great schools” correctly. Now, thanks to the new data provided by SEDA and the tools on Fordham’s new website, we can finally identify metro areas that have a right to brag about the quality of their school systems and charter schools—as well as places that would be well advised to stop patting themselves on the back and get a move on.