Here follows the first entry in Fordham’s “Charter School Policy Wonk-a-Thon,” in which Mike Petrilli challenged a number of prominent scholars, practitioners, and policy analysts to take a stab at explaining why some charter sectors outpace their local district schools while others are falling behind.

Why do some charter sectors outpace their local district schools while others are falling behind? To begin to answer this question, let me pose a second. Among high-performing charter cities, why does Boston outperform other “good” charter cities (by a country mile)?

Hey, I get it. We Bostonians tend toward annoying self-promotion. Sox, Pats, Bruins, Celts for a while, Harvard, John Hancock, etc. Let me just concede up front that there’s an irritating quality to my question.

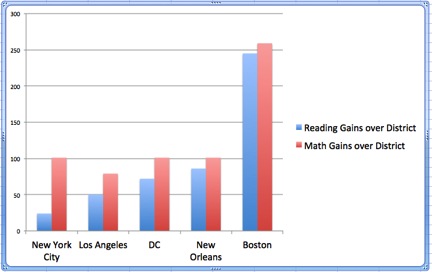

But look at the chart. Here are CREDO’s top cities, measured in “days of learning.”

The difference between Boston charters and, say, D.C. charters is bigger than the difference between D.C. charters and their district schools. If we’re to discover why the average charter in D.C. or New Orleans is so much better than the average one in, say, Detroit or Miami, I believe we need to answer the Boston question.

Let’s dispense with some theories of why Boston charters outperform these other cities, beginning with the obvious.

1. Is this a boutique story? It is true that Boston’s charters educate just under 9,000 students. Thus, one could say that even if Boston is generating gains three times larger for a typical kid as compared to D.C., isn’t D.C. at least “as good” by affecting roughly four times more kids? (For more thoughts along these lines, read this excellent piece from Neerav Kingland of NSNO.) Both scale and quality matter. The key point, I believe, is that when cities like D.C., New Orleans, New York, or Los Angeles had 9,000 kids in the charter sector, their charter sectors were not anywhere near as high performing as Boston’s. And of the several cities with charter enrollments in the range of Boston’s, none have particularly good charter results, let alone Boston-type outlier results. As such, the smaller size of the Boston charter sector does not seem to be the main cause of the Boston results.

2. Is it because of Massachusetts’ strong charter-school authorizer (the state board of education)? I do believe the authorizer has been solid overall. The law is reasonable. Two Boston charters were shut down in the early 2000s, which is also good. Yet the same authorizer with the same law also begat the forty-plus non-Boston Massachusetts charters, and CREDO shows those generate almost zero value-add gains compared to district schools. So I don’t think the authorizer/law question can explain the Boston/non-Boston variance.

3. Caps have mattered, I believe, in combination with good authorizers. My own charter application in 1998 was rejected, in a year where 48 applied and 8 were approved. The rejection was appropriate, in hindsight. We reapplied and then were approved in 1999. The state’s lifting of the “9 percent of a district’s enrollment cap” in 2011 in response to Race to the Top had a helpful “smart cap.” It led to top Boston charters like Edward Brooke, Excel, KIPP, and Uncommon each opening two more schools—not ten, not zero.

To be sure, many other cities and states have caps, and their charter schools are on average pretty average—Rhode Island and Maine, for instance. Washington State has caps, and let me say this: if there were a futures market and I could “short” the 2020 CREDO study of their schools, I’d do it. The early signals are not promising (though I have friends there laboring hard and who’d strongly disagree). And if I could “long” the 2020 Boston CREDO study and bet on Boston kids making even bigger gains, I would. I’m not pro-cap.

Another important question: Have caps “helped” Boston families? No. Several top charter operators in Boston fled to New York City during the 2004 to 2011 period, where Mayor Bloomberg welcomed them. If Boston had no caps, I suspect there’d be more good charters here, even if some more turkeys had also opened. So Boston families probably were hurt, in net, by the Massachusetts cap. Meanwhile NYC families benefitted by the Massachusetts cap, by getting good charters that might have otherwise opened in Boston.

In sum, laws, regulations, authorizers—yes, they do matter. But they’re not the main reason why Boston’s charter kids trounce charter kids in the other high-performing cities. (For more thoughts on this, see this piece by Ed Liu of the Boston Teacher Residency.)

4. I do not think that the funding Boston’s charters receive versus that in D.C., New York, New Orleans, and Los Angeles explain the difference. D.C. charters spend more than Boston charters. If you factor in that New York charters often have access to rent-free public buildings (a fact that gives Mayor De Blasio high blood pressure), the per-student spending looks pretty similar. New Orleans and Los Angeles fund their schools at far lower levels, but so do the districts they are “competing with” in the CREDO study. And I don’t think KIPP finds across its network a tight correlation between money and KIPP versus KIPP performance. It ain’t about the money.

5. It’s not that Boston’s district schools are much worse than those in New York, D.C., etc., such that it’s “easier to outperform” them. NAEP data would suggest Boston is strong relative to other high-poverty districts.

So why Boston? Here’s what I think.

Talent

This is part of the story. But there’s a lot of nuance to it.

Boston has a lot of young college grads from prestigious schools, but so do New York, D.C., and Los Angeles. In New Orleans, there’s an unusual talent infusion from Teach For America, TNTP, and other leading ed-reform orgs. Boston is talent-friendly place, for sure, but so are the other cities.

Scott Given, who founded a network of turnaround schools called Unlocking Potential, argues that talent is indeed a big part of the answer in two main ways. He writes,

a. In the 1990s, some incredible people were drawn to launching and leading charter schools in Boston. The list includes Brett Peiser (now CEO of Uncommon in NYC), John King (now commissioner of education in NY State), Evan Rudall (now CEO of Zearn), and others.

Anyone studying the out-sized success of the Boston charter sector should understand (1) what factors drew these visionaries to the sector in Boston; (2) from where they learned how to design and lead such great schools; and (3) how closely they worked together exchanging ideas about the design and management of tremendous urban public schools.

b. The flow of top talent between Boston’s charter schools matters, too.

An examination of the “web” of talent in Boston (and it would be really cool if someone drew this up at some point) suggests that many of the best schools have been deeply influenced by other top Boston schools -- yes, through the sharing of ideas, but perhaps more critically, through the movement of people.

I agree. Harvard matters. That’s what brought Brett, John, Evan, and many others to Cambridge/Boston. They stayed long enough to open unusually good schools and then left. Others stayed. (Check out a Scott Given’s quick example of how Boston charter people spread.)

Idea Transfer

Because of coopetition (i.e., cooperation plus competition), successful practices have spread quickly.

Jon Bassett, a star history teacher and founder of Newton Teacher Residency in suburban Boston, invokes Jared Diamond:

This may be a stretch, but the comparison of Boston Charters to other cities reminds me of part of Jared Diamond’s thesis about the rise of the West, which he laid out in his magisterial book Guns Germs and Steel.

Diamond suggests that the political geography of Europe might help to explain that region’s surge to power after the year 1000. Europe is a small continent, and it was crowded with many states competing for resources and power. These states are linked by easy communication and trade routes. Thus successful innovations (the 3-field system, good state record-keeping) spread quickly, because the success of a neighboring state was immediately visible, and failure to adopt the innovation meant that you got left behind fast -- and probably conquered. This environment created a hotbed of innovation and adaptation, which propelled Europe to global dominance.

When I looked at the graph about charter school success, the obvious difference between Boston and the other cities is size. Boston is smaller, and its charter community is competing for finite resources (a fixed number of charters, students, and the same philanthropic donors). Those who don’t compete effectively will lose out. Boston’s charter community shares ideas readily (like MATCH’s tutoring program), and charter leaders have strong incentives to adopt successful innovations quickly.

No Excuses

The single biggest factor in why Boston charters create larger gains for kids is that it has the highest proportion of self-identified, authentic adherents to the No Excuses model. (“Authentic” is important qualifier.)

Set aside for now Jay Mathews’s excellent questions about the No Excuses name, set aside the question of how widely replicable the model is (see John Thompson here), and set aside all the other concerns with the model, whether it works, and if so, why it works (see Matt DiCarlo here). The question of why Boston kids win in this particular CREDO metric is also a No Excuses question.

Boston has a higher proportion of self-identified No Excuses schools than Los Angeles, New Orleans, D.C., or New York. About two-thirds of its charters are of the No Excuses variety.

Now the whole story falls into place.

In terms of idea sharing, it’s a lot easier to discuss the nuance, the details, when you agree on something big. For example, basketball coaches who meet to discuss the two-three zone defense learn more about key details versus when coaches meet to discuss “defense”—because the first question is man or zone, the second question is what type of zone, and so on.

In terms of staff mobility, folks can move more easily from one school to another in the Boston area, in part since we agree on many key ideas. In terms of attracting talent, the task has been more “talent who want to succeed and can succeed in No Excuses schools.”

This offers insight into why many efforts to copy the best practices of No Excuses schools as turnaround schools haven’t worked: the buy-in hasn’t been authentic. By contrast, a healthy outlier among turnarounds in the USA has been the Boston-based Unlocking Potential. Their success is due in part to the fact they’re not trying to “convert” staff to No Excuses ideas. Instead, they’re hiring teachers directly from top No Excuses charters.

The Charles Sposato Graduate School of Education (SGSE), embedded at Match Charter Schools, provides teachers to all the No Excuses charters in Boston. SGSE is able to train rookie teachers whose students go on to get unusually high value-added numbers.* There are many things that make SGSE different from other teacher-prep programs, but one is the specificity of instruction. The message: “Here is what will be expected of you in a No Excuses school. That job is not right for everyone, but if it’s the one you want, we’ll help you practice, practice, practice to become good in that context.”

Moreover, SGSE is able to get instructors and coaches from the various No Excuses charters, which just accelerates best-practices transfer, beyond that of other charters in other cities. Will Austin from Uncommon teaches a rookie teacher about effective math instruction; that teacher, in turn, takes a job at KIPP; now Uncommon’s ideas have moved to KIPP; and so forth. When Kimberly Steadman of Brooke teaches literacy to a rookie teacher, even fellow instructors (from other charter schools) perk up and jot down notes.

Individuals Matter

Harvard’s Kay Merseth introduced many folks to the very idea of charters with her class on the subject. Moreover, she serves as a critical friend to charters (her book argues for more rigor in No Excuses schools, predating the Common Core push along the very same lines).

Finally, one woman can claim a singular place in influencing many of these schools: Linda Brown of Building Excellent Schools (BES) and formerly of the Charter School Resource Center. Excel and Boston Prep came directly from BES, and Roxbury Prep, Boston Collegiate, Academy of the Pacific Rim, and Match were all significantly influenced by Linda and, through her, by Lorraine Monroe of the School Leadership Academy.

Conclusion

The No Excuses charter isn’t a cure-all. But the reason CREDO shows New York City, New Orleans, D.C., and Los Angeles with very large gains is because they have several No Excuses charters, and the reason Boston outperforms these cities is because it has even more.

Michael Goldstein was founder of Match Charter Schools, now Match Education. He acknowledges the Boston Celtics will be bad for several years but has high hopes for the Revis-led Patriots. He believes one best practice that can scale to all types of schools is teachers calling parents.

* One measurement challenge for the small teacher-prep program at Match: while grads seem to have value-added gains far higher than teachers from any other graduate school in the nation, they’re also mostly hired by Boston charters. So the obvious problem is that it’s very hard to separate training/selection effect from “school effect.” If any funders are reading: along with Harvard economist Tom Kane, Match hopes to run a randomized control trial of its teacher-prep program to figure out if indeed the training is unusually good.