Many state teacher pension systems are woefully underfunded, impose significant costs on teachers and schools, and shortchange those who decide to change professions or move to other states. Some retirees, seeing benefits pared back, are unhappy. Bellwether Education Partners, a national think-tank, recently gave a number of states’ traditional pension plans an F, citing how poorly they serve teachers and taxpayers.

What can policymakers do? One possibility is to slash benefits and extract even more from teachers and schools to pay down systems’ unfunded liabilities—the shortfall in its assets versus pension obligations. This approach would be wildly unpopular, would suck money out of classrooms and teacher pocketbooks, and wouldn’t solve the underlying problems with administering a teacher pension system. Another alternative is bailout—injecting billions into the pension fund to cover its debts. But this would raise the specter of moral hazard, i.e., reinforcing the same behaviors that shipwrecked systems in the first place. Of course, it would also require huge sums of money, funded by cuts to other government programs or higher taxes.

The quicker we forget those options, the better, along with reckless pension obligation bonds (covering debt by issuing more debt). Fortunately, there are more sensible solutions that would put states, which include Ohio, on stronger footing. Let’s take a look at three alternatives:

Option 1: Create plan options and make the default the defined contribution (DC) plan. A handful of states, including Ohio, offer new teachers a choice in retirement plans. In the Buckeye State, they can opt into one of three plans. Briefly, they are as follows:

- Traditional pension, a.k.a., defined benefit (DB) plan, which offers teachers lifetime income, the amount of which is based on a formula that accounts for years of service and final average salary. The option works well for teachers who teach in one state for their entire career, but not those who separate before retirement age. Because pensions are “backloaded”—benefits accrue slowly for about two decades and then spike toward the end of the career—early leavers receive inadequate benefits.

- 401(k)-style, defined contribution (DC) plan, in which teachers and their employer contribute to an individual savings account. These contributions, plus investment returns, determine the amount saved for retirement (as opposed to a formula). The DC option doesn’t offer guaranteed income for life, but it’s portable, meaning short- and medium-term teachers aren’t penalized for choosing to leave for teaching jobs in other states or to pursue other career opportunities.

- Hybrid plan, which combines elements of the DB and DC plan. Teachers contribute to an individual retirement account and receive a modest pension.

The issue in Ohio is that, by default, newly hired teachers participate in the DB plan if they do not select a plan within their first year of work. Three in four don’t make an affirmative choice, and as a result, the vast majority end up in the DB. In a 2021 Fordham report, pensions expert Chad Aldeman made a strong case for changing Ohio’s default to the DC plan, something Florida did five years ago. His calculations show that the state’s DC plan provides today’s entering teachers more retirement wealth than the DB option.

If a state creates plan choices, it should set the default to the DC option, which is likely to provide the most benefits to the majority of entering teachers. This policy option would retain the DB and hybrid plans for entering teachers who prefer them.

Option 2: Close the DB plan to new teachers, and offer a cash balance (CB) plan. Ohio and nearly every other state do not currently offer this option, but they could require new teachers to enroll in a CB plan, as Kansas did in 2012. This structure has features of both DC and DB plans. Like a DC plan, contributions are deposited into individual accounts. But unlike a DC plan, where teachers make investment decisions, the state invests on their behalf and deposits interest each year into accounts, the rate of which can be tied to the “risk-free” return (e.g., 3 percent). The state can still invest in riskier assets, and in years of strong returns—for instance, 7 percent—it may choose to pay a higher interest rate or set aside gains to offset losses in a downturn. When teachers retire, the savings accumulated in their accounts are annuitized, and the system makes payments for the duration of their retirement.

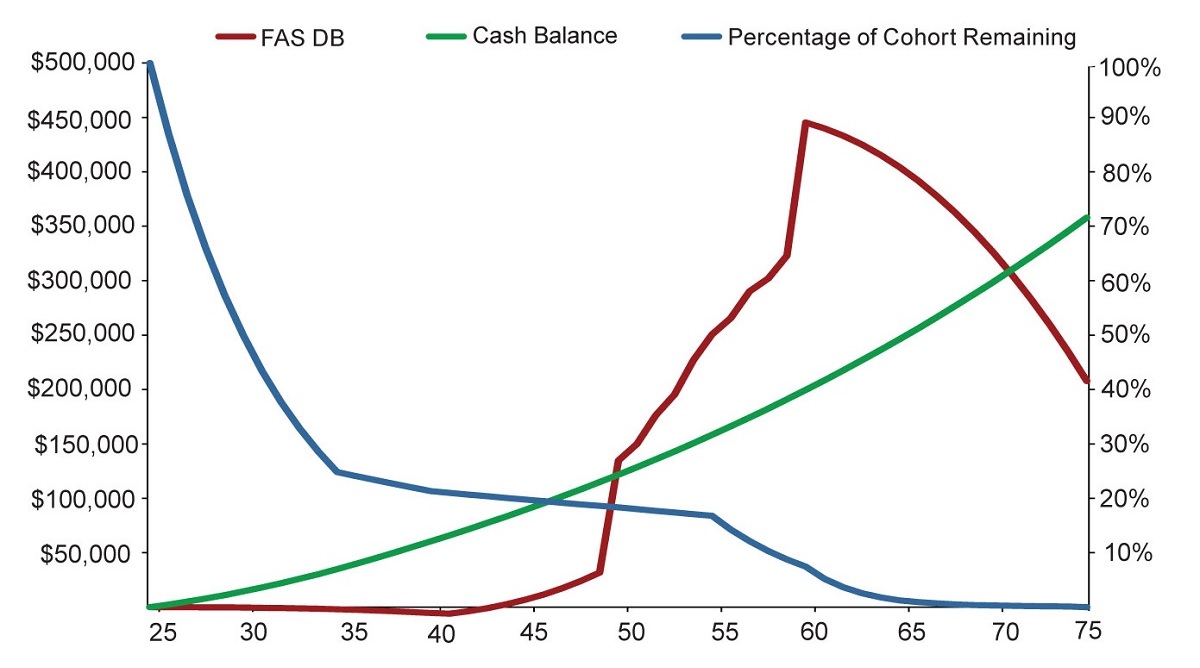

In contrast to a traditional pension, CB plans treat short- and medium-term teachers fairly. As Figure 1 below illustrates, CB plans “smooth” the accrual of retirement benefits over a teacher’s career instead of backloading them. Thus, teachers who separate early have more retirement wealth when they leave. In the bottom left portion of the chart, we see a “wedge” between the CB line in green and the DB line in red. This represents the gains under a CB plan in wealth for the roughly 80 percent of teachers who work for less than twenty-five years in this school system. Though a minority, entering teachers who work more than twenty-five years would receive less under a CB than DB plan. That occurs because a CB plan doesn’t “cross subsidize” older teachers at the expense of younger ones.

Figure 1. Employee-sponsored retirement wealth over time, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Source: Josh McGee and Marcus Winters, “Modernizing Teacher Pensions,” National Affairs (2015).

Option 3: Close the DB plan to new teachers, and offer a DC plan. In an effort to attract a more mobile workforce and to reduce legacy costs, this is exactly what U.S. businesses have done over the past three decades. Today, approximately 80 percent of private-sector workers with retirement benefits are in a DC plan. State governments, perhaps because they don’t compete in the same way as private companies, have been slower to shift from pensions. Alaska is the only state to have closed its DB plan for teachers and now offers only a standalone DC option. A few other states, however, have transitioned to DC plans for other state workers.

Much like the CB plan above, benefits in the DC plan accrue evenly across a teacher’s career and are fully portable. Thus, teachers who separate early have considerably more retirement wealth than in the DB plan. However, unlike the CB plan, which guarantees a minimum interest rate each year, teachers directly control the investment decisions in a DC plan. Depending on those choices—which can be wisely vetted by plan administrators—they may generate larger or smaller returns than the interest rate in a CB plan. From the view of states, a DC plan is the most straightforward and predictable option. The state bears no investment risk and no complicated actuarial calculations are needed to project pension obligations. In fact, there are no unfunded liabilities at all in a DC plan.

The notable drawback to a DC plan is that retirees could outlive their savings. In states like Ohio where teachers do not participate in social security, policymakers should consider enrolling teachers in the program. Social security offers a baseline amount of income for life, protecting retirees who live well into their golden years. Of course, the catch is that benefits are paid for through payroll taxes levied against employers and employees (12.4 percent combined). States would need to adjust DC contribution rates to compensate for the new taxes. In terms of process, teachers would need to vote to participate in social security.

—

Traditional pensions fail to justly compensate a large portion of teachers for their work every year in the classroom. They’re often massively expensive and incredibly complicated. Over the past decade, retiree benefits have been in flux. The politics of pension reform won’t be easy, and there’d be much to sort out, especially if states close their DB plan (figuring out how to address unfunded liabilities). But all is not lost. Policymakers have options that can make retirement more fiscally sustainable and fairer to a next generation of teachers. It’ll take much hard work, but kicking the can down the road is a short-sighted option.