I’m a decades-long supporter of school choice in nearly all its forms and likely to remain that way so long as traditional, district-operated public schools ill-serve so many kids, produce such widespread mediocrity by way of achievement, give parents so little say in so many matters, and cater to the interests and priorities of the adults in the system more than the needs and interests of children, taxpayers, and the general public.

Whew! Yes, and I mean it, and few will be surprised by that paragraph. That said, however, I’m getting seriously unnerved by how the country is coming apart, by how many people are putting pure self-interest ahead of anything smacking of the public interest, by mounting intolerance of those who are different or who disagree, and by diminishing confidence in the shared values, institutions, principles, and traditions that have held us together as a nation, most of the time anyway, for the better part of three centuries.

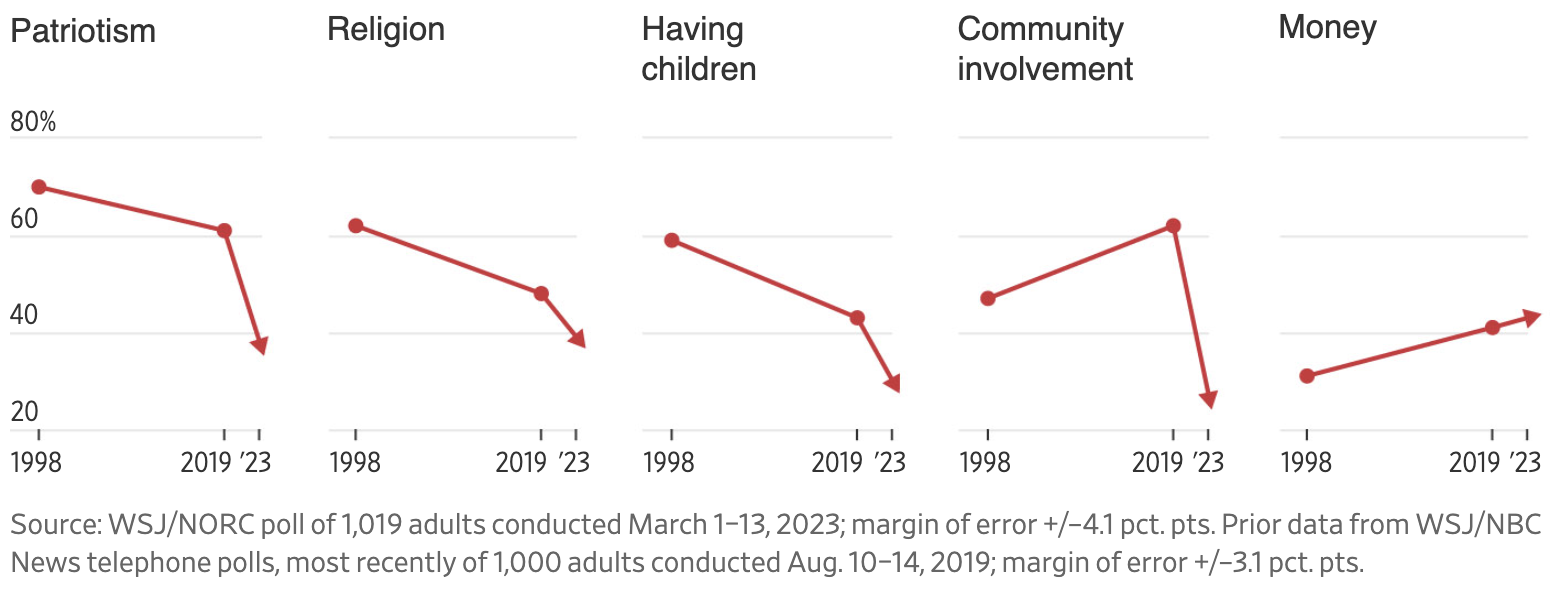

Which forces me to wonder whether putting all our education hopes in markets, self-interest, competition, and “invisible hands” just might be contributing to—at least moving in tandem with—other fissiparous forces that are weakening the valuable shared assets that we inherited from earlier generations. Recent surveys certainly suggest that mounting public support for school choice is coinciding with diminishing confidence in shared institutions and public values of all kinds, including patriotism itself.

Figure 1. Percentage of respondents to WSJ/NORC poll who said these values are “very important” to them, 1998–2023

It’s not just markets and conservatives, of course, that may be pushing—I attribute no intent here—against those shared institutions and values. Identity politics and the overreach of DEI and innumerable forms of intolerance and cancellation on the left are, to me, a lot more damaging to that inheritance. So, too, are many of the core tenets and practices of progressive education, such as children learning—on their own—that which interests them rather than participating in shared lessons, readings, and interactions.

But maybe we who yearn for more and better schooling options for America’s kids should try to do our part. Maybe we should pause for three seconds and ask whether there are ways of furthering choice while also helping to sustain, even strengthen, the shared inheritance.

We’ve known—I’ve surely known—for years now that pure market forces in K–12 (and higher) education do not reliably yield more effective schools and better-educated children. Sorry, Milton F and Corey D and a host of other living colleagues. Too many things go awry in that marketplace, from parents who make bad (if understandable) choices to greedy school operators who don’t care about outcomes, not to mention kids who lack competent adult guides. So, for years, I’ve urged a “regulated marketplace” that requires prospective school operators to demonstrate their bona fides and holds all schools to account for their educational results, thereby constraining the market to choices that (one would hope) include a sufficient array of quality options. Sadly, though, we know that the constrained market often fails to yield enough good schools accessible to enough needy kids, so we continue to struggle with the resulting tensions and tradeoffs. (Who else remembers the films “Waiting for Superman” and “The Lottery”?) We know, too, that the established adult interests of public education adore constraining the marketplace and do their utmost to limit options all over the place, even while themselves failing to deliver a quality product to millions of kids.

Which says to me that regulation of the school-choice market is a mixed blessing—a necessary evil, if you will—but also one that in no way deals with the problem of our weakened inheritance and our coming apart.

It also has to be noted—this really hurts—that we’re seeing mounting evidence that increases in public-sector school choices, charters especially, are bad for Catholic parochial schools and perhaps for other “traditional” private schools that, on the whole, have striven to maintain some of that inheritance via faith, values, morals, and example. Will the spread of ESAs send more kids back into those private schools? Or will more choice result in more coming apart?

Yes, I want it both ways. I want a plethora of quality school options for families, but I also want our “education system” in its variegated forms to strengthen rather than weaken our shared inheritance and pull us more together than apart.

Putting some reasonable limits on fissiparous alternatives to that system could help a bit, such as booting more kids off social media for larger portions of their lives, maybe nudging them back to Little League, Cub Scouts, and story hour at the library.

Back in school, there could be hope in the realms of curriculum and perhaps graduation requirements, at least if these were more widely agreed upon and shared across the various K–12 delivery arrangements. That’s more or less how most other modern industrial democracies manage to balance school choice on the one hand with national unity on the other: The schools may be independently operated and diverse in various ways, but they generally adhere to a common core curriculum.

I understand that curricular diversity is a core tenet of U.S.-style school choice, and I’m well aware of the fracas over Common Core and such, but I’ve also been pointing out the latent (if limited) consensus around most of the country in realms such as civics and history curricula. If we worked at it, we could find something similar in the (arguably) less contentious realms of math, science, and even English. Which is to say, it should be possible to develop a framework of shared curricula spanning big chunks of the main K–12 subjects, curricula that would be acceptable to the vast majority of Americans and could be taught in the vast majority of schools of all sorts. Schools would naturally add and embellish, and in time, perhaps two-thirds of the curriculum might be “common” across almost all elementary and middle schools, maybe half in high school. If it pains you to think of commonality across state lines, we’d get somewhere by pulling it off within them.

That won’t unite a divided land. But it might slow the coming apart.

What else? A regulated marketplace and partially-shared curriculum can’t be the whole story. I’m not so bold as to forecast a truce in the culture wars. But what else can we devise that might better balance our hunger for school choice and diversity with America’s need to preserve the best of its inheritance?