When I read the article in The 74 by the Colorado Education Initiative’s Rebecca Holmes introducing a one-day conference that would bring together educators, families, and students to discuss what school quality is and who decides, I looked at who would be speaking. As most of them held positions different from mine, I decided to attend. It turned out to be an enlightening day.

The first speakers highlighted the conference’s goal of “building an accountability system designed for family, community, and educator needs,” and the key questions participants would address: “What do we value? What defines school quality? And what evidence will we accept that quality standards have been met?”

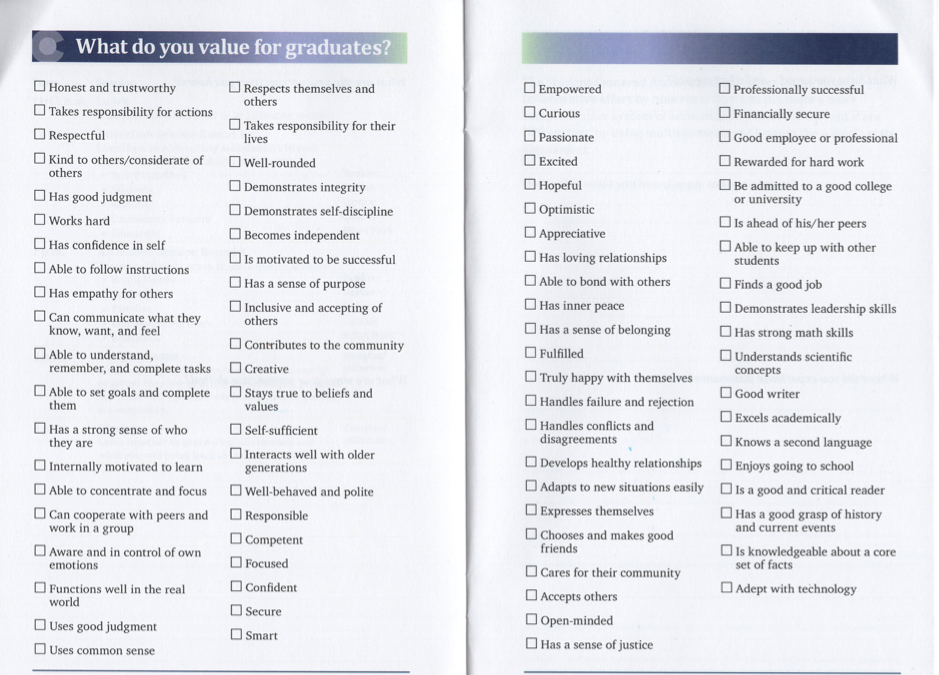

The program given to participants included this list of possible student outcomes for attendees to consider. The order was interesting, to say the least:

As the day wore on, some predictable themes kept coming up:

- Teachers are the experts at assessment.

- Standardized tests have many limitations, and should be deemphasized or eliminated.

However, other speakers raised points that clearly made some in the audience uncomfortable:

- The acceptability of locally designed performance criteria critically depends on whether the associated metrics are reliable, valid, and rigorous.

- It also depends on whether there is evidence that outcomes on these metrics are significantly affected by school-level interventions.

- Student assessment should require the transfer and application of demonstrated concepts.

For me, the most interesting part of the day was when one speaker summed up what seemed to be the dominant audience view by saying that “accountability means continuous improvement.”

I’ve spent forty years in the private sector, including leading a professional engineering company, and I fully agree that continuous improvement is critical and depends on efficient feedback based on clear goals, appropriate metrics, and effective assessments. But I also know that a continuous improvement process is not the same as an accountability system.

Accountability systems include consequences at the group and individual level for both good and bad results. Unfortunately, throughout last week’s meeting, consequences weren’t mentioned at all. For private sector and military leaders, that absence speaks volumes.

There is a reason why employers today increasingly require job applicants to take a broad range of assessments covering reading, math, and writing proficiency, as well as critical thinking, complex problem solving, and other advanced skills. Employers have largely lost confidence in academia’s accountability systems, in both K–12 and higher education. After last week’s meeting, it seems very unlikely that is going to change.