Ohio’s draft plan for implementing the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) came out earlier this month, and we at Fordham continue to analyze it and offer our thoughts. In a previous article, I argued that Ohio’s plans for improving low-performing schools were underwhelming. But there is an even more worrisome set of details worth pointing out and rectifying—namely that Ohio’s proposal will likely result in a vast number of schools and districts being labeled as failing and routed into a burdensome and ineffective corrective action process.

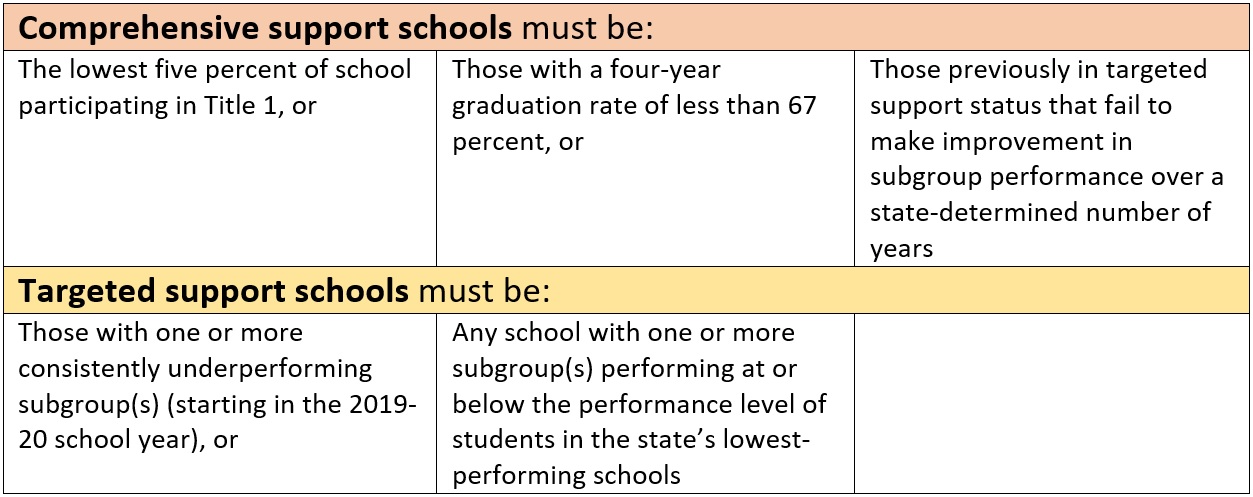

For starters, Ohio’s ESSA plan moves beyond what’s required by law when it comes to identifying “low-performing” schools. Federal law requires states to have at least two buckets for school improvement—comprehensive support and targeted support (or the equivalent of what Ohio is naming “priority” and “focus” schools, respectively). The law is direct in spelling out how states should place schools in either category (see Table 1).

Table 1: ESSA requirements

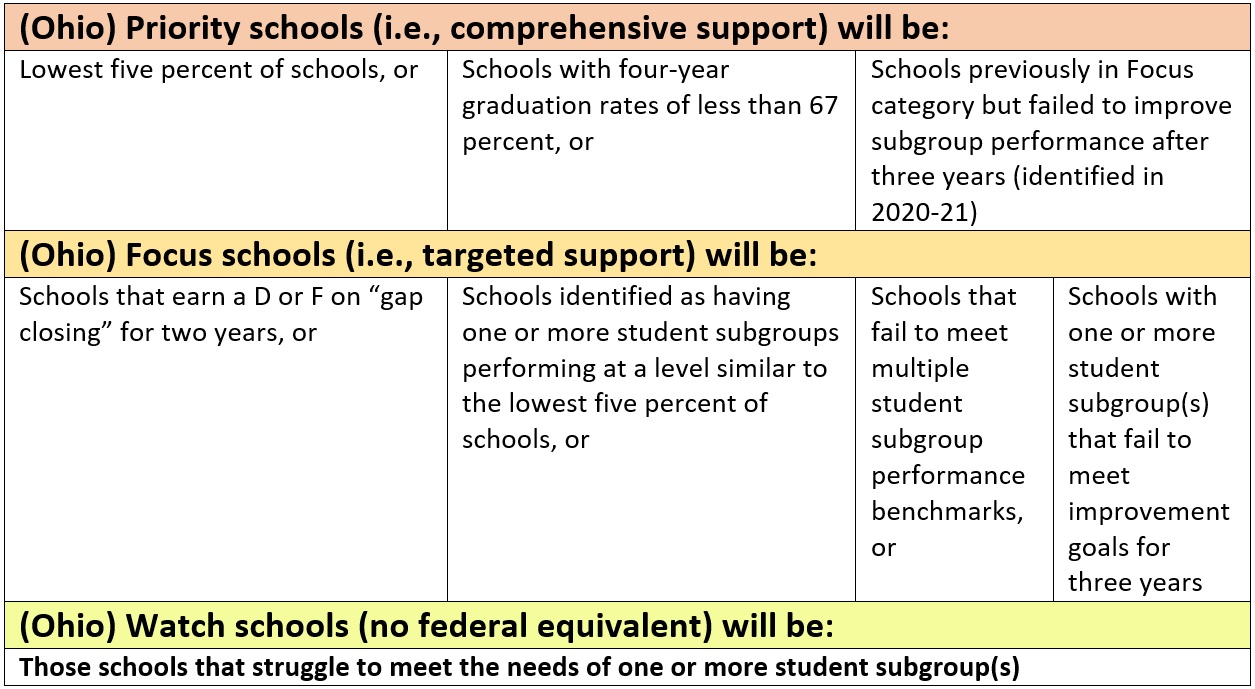

Now take a look at Ohio’s proposed criteria below.

Table 2: Ohio’s proposed implementation of ESSA’s requirements

There are several problems with this approach. First and most glaringly, Ohio opted to add a third category to the mix: “watch” schools, nebulously defined in ODE’s plan as “schools that struggle to meet the needs of one or more student subgroup(s) as outlined in state law.” Ohio should clarify what this means or consider scrapping the category altogether, as it’s not necessary under ESSA and the state has already cast a wide net in terms of identifying priority and focus schools. Specifically, the inclusion of the gap-closing measure as a way to determine eligibility for targeted support does not inspire confidence based on current grades. Ninety-three percent of Ohio districts earned a D or an F on gap-closing in 2015-16, with the vast majority of those (87 percent) getting an F. Only two districts in the entire state earned an A.

To be fair, it appears that Ohio is changing its gap closing calculation—to fall more in line with recommendations that my colleague Aaron explored here last year. Still, until the new metric is fully rolled out, Ohio may want to tread carefully in tying sanctions to the gap-closing grade. It could also lengthen the timeframe to three consecutive years or make some of these qualifiers “and” (instead of “or”).

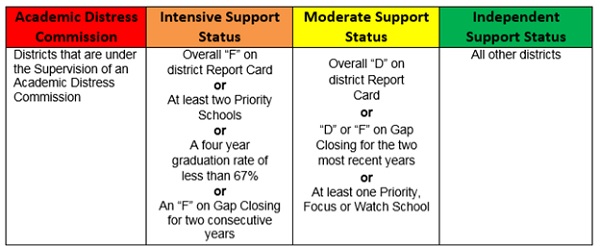

Ohio’s plan for identifying low-performers becomes even more worrisome when considering the implications for districts. Take a look at the table below—copied directly from Ohio’s ESSA plan. ESSA requires that states provide “technical assistance” to districts that serve a significant number of schools identified for support, which includes review by the state, quarterly or biannual improvement plans, submission of student outcome data, and more.

Given that the overall report card calculation relies disproportionately on factors that correlate with demographics and relatively little on student growth, it’s likely that most low-income districts will find themselves in intensive support. By my rough estimate, about twenty districts—primarily those located in Ohio’s cities or inner-ring suburbs—would fall into intensive support status. That’s about three percent of Ohio districts.

But if future scores are anything like current scores, the inclusion of the gap closing measure will place a vast majority of schools into intensive or moderate support status. And any district with just one identified school whatsoever—even an ambiguously identified “watch” school—will be placed on the support spectrum.

Rather than going deep and requiring intensive, dramatic change among its very lowest-performing schools, Ohio appears to have taken the opposite approach to school improvement—wide and shallow. By adding a new, non-required “watch” status for schools and creating multiple (very likely) scenarios for districts to fall on the support continuum, there’s a very real chance that just about everyone will have to succumb to improvement plans. This dilutes energy and resources and is not a reasonable ask, nor will it yield benefits for most of the schools asked to undergo it. New compliances processes and burdensome paperwork create extra work for everyone involved—both the state and the schools and districts under monitoring. The extra workload is all the more unbearable give Ohio’s currently proposed scattershot strategy for improving schools.

There are chronically low-performing schools in urgent need of attention, where kids are losing their one opportunity to get an excellent education. These are the schools (and districts) that ODE should focus its efforts on—the lowest five percent or perhaps even one percent of schools—in a concentrated strategy to raise student outcomes.