This week’s news of sharp declines on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) gave partisans yet another chance to relitigate the debate over keeping schools closed for in-person learning for much or all of the 2020–21 school year. Conservatives (myself included) have been eager to identify the teachers unions as the primary culprits.

And we’re not wrong. Many union leaders behaved despicably during the late summer and early fall of 2020, appearing more interested in spiting President Trump’s and Secretary DeVos’s calls to reopen schools than in finding constructive ways to launch safely. Shame especially fits those union leaders who attacked reopening advocates as racists or murderers—even as progressive leaders in so many other countries were reopening their schools enthusiastically and with little ill effect.

It’s also true that in places where teacher unions are the strongest—mostly the bluest states and districts—schools remained shuttered the longest, generally not reopening for in-person instruction until vaccines were available for teachers in spring 2021, and in some cases not even until the following fall.

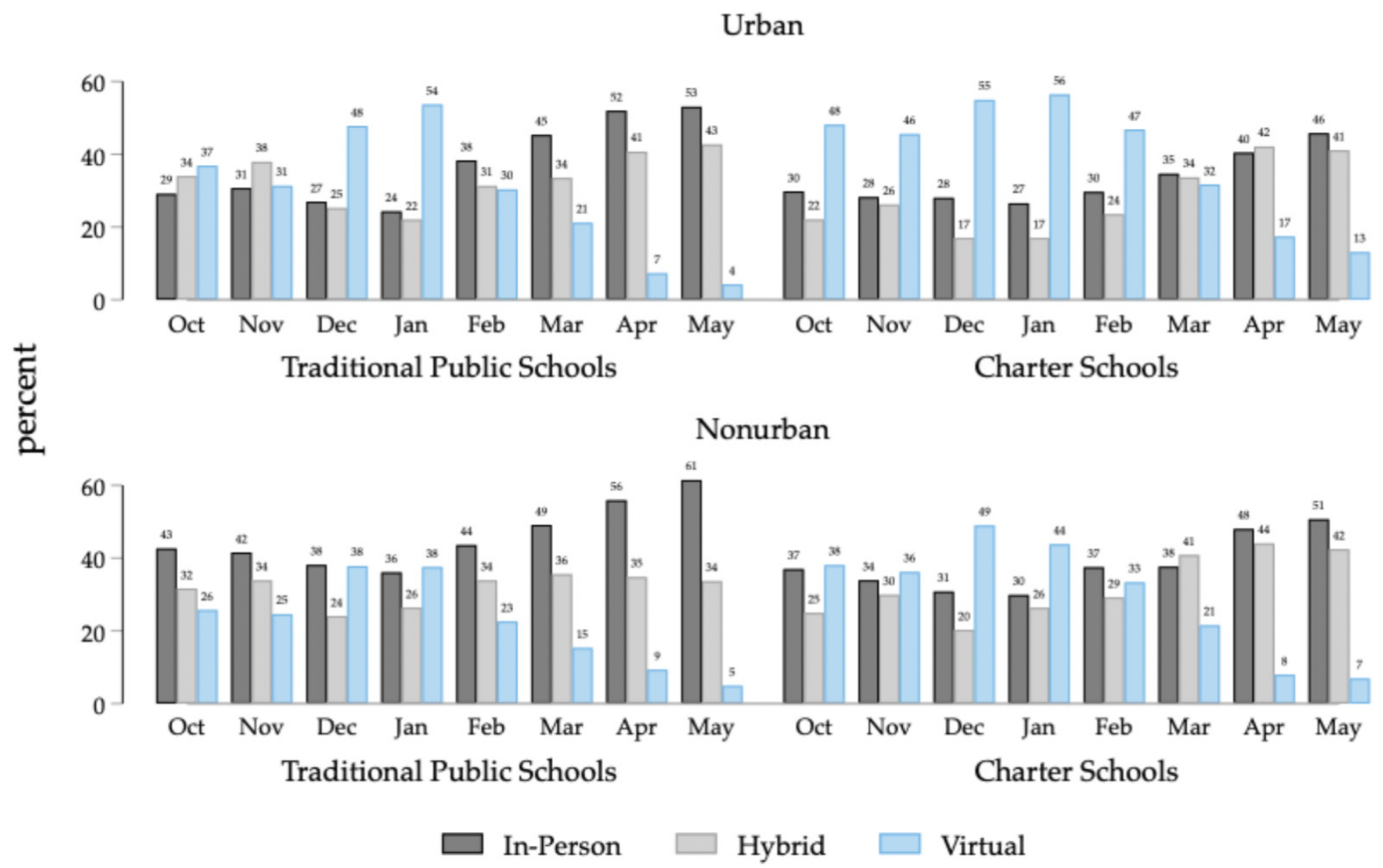

But there is one complication to the blame-the-unions narrative that we conservatives should acknowledge: the curious case of urban charter schools. These schools, which boasted a decades-long track record of improving student achievement and other outcomes in the pre-Covid era, were actually more likely to remain completely virtual during the first half of 2020–21 than their urban district counterparts. That was the conclusion of an analysis by Sarah Cohodes and Christine Pitts for the Center on Reinventing Public Education that was published this past January, and which includes this figure:

We already know from rigorous studies from the American Institutes for Research, Dartmouth College, Harvard, and NWEA that schools that stayed closed for in-person learning the longest saw their students fall furthest behind. So we should not be surprised that NAEP brought bad news for all public schools, including charter schools. Indeed, declines for charters were just as bad, and in some cases worse, than those for traditional public schools.

Which raises the question: Why did so many charter schools stayed closed for in-person learning for so long? Nine in ten charter schools don’t have teachers unions, so union leaders can’t fairly be blamed for their decisions. What could?

After talking to others in the charter sector, including school leaders, I have several hypotheses. The strongest is simply that these are schools of choice, and many charter parents were afraid to send their children back to school before vaccines were widely available. Keep in mind that charters disproportionately serve large numbers of Black and Hispanic parents, most of them low-income and working class. And as we all know, tragically, these are the very communities that were hit hardest by Covid, especially in the early months of the pandemic. There was no point in charter schools reopening for in-person instruction only to have few parents send their kids to class, or for families to transfer their students to district schools (which remained closed) so that they could remain at home trying to learn online.

(Private schools faced different realities: strong incentives to reopen as soon as possible, given how hard it would be to persuade parents to make hefty tuition payments for remote instruction. It’s not surprising, then, that Catholic schools did relatively well on NAEP from 2019 through 2022.)

Another factor that likely nudged many urban charters to remain all-virtual for so long was local politics. Located as they are in deep blue parts of the country, charters operated under strict public health guidance coming from officials who tended to be much more cautious about reopening all manner of institutions than those in purple or red communities. For example, in Columbus, Ohio, home to a handful of charter schools that we at Fordham authorize, the city health commissioner was urging all schools not to reopen for in-person instruction in the fall of 2020, even as the health department in suburban Franklin County was laxer. School reopening patterns largely followed suit.

Finally, even if their schools were not unionized, charter leaders had to worry about maintaining the trust of their teachers. Often operating in difficult budgetary circumstances, and already unable to afford to pay their teachers as much as nearby districts, making teachers return to in-person instruction when all the schools around them were still closed was risky.

Those are my hypotheses, though I understand that some readers may consider them to be excuses. And yes, the understanding I’m showing toward charter leaders and the tough decisions they made should be extended to educators in the traditional public schools, as well. Nothing about the pandemic was easy, and making the case to reopen schools when vaccines were not yet available was an enormous leadership challenge, regardless of sector.

But by now, we should all acknowledge the evidence that keeping schools closed for so long was damaging to students in so many ways. Not only did it result in massive learning loss, as well as social and emotional challenges for many children, it also kept many parents from returning to work, and does not appear to have helped much in terms of reducing the spread or deadliness of Covid. We may not have been able to force nervous parents to send their babies to school, but we could have ensured that in-person schooling was at least available for those who wanted it, and we could have tried harder to convince families that school was a safe place to be.

The best act of contrition is for us to ensure that the Covid generation now gets everything it needs to be made whole: the extra resources and instructional time to make up for learning loss, and the social and emotional support to get back to full health, physically and emotionally. That still is not enough, but it is the least we can do.