Editor's note: This is the fourth post in Fordham's 2016 Wonkathon. We've asked assorted education policy experts to answer this question: What are the "sleeper provisions" of ESSA that might encourage the further expansion of parental choice, at least if advocates seize the opportunity? Prior entries can be found here, here, and here.

Education reformers and policy makers across the nation have spent the months since the Every Student Succeeds Act’s (ESSA) passage debating the merits of various approaches to identifying low-performing schools—which indicators, how much weight, indexes or no indexes? We’ve spent a lot less time debating an even more important question: What are states going to do once those schools are identified? At the Foundation for Excellence in Education (ExcelinEd) we’re hopeful that states will leverage the power of parental choice to spur rapid and dramatic turnaround in their lowest-performing districts and schools.

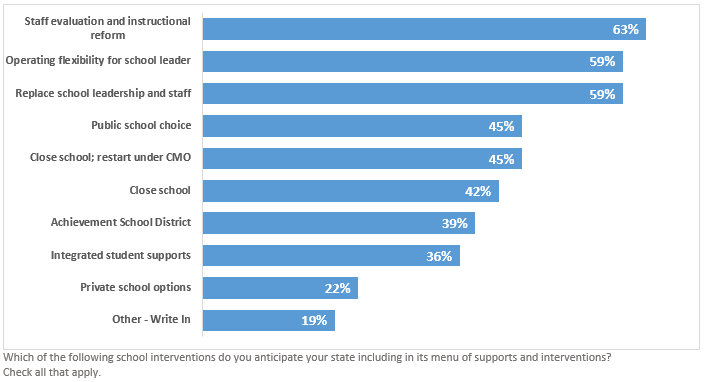

But in April 2016, we surveyed nearly one hundred of our state education reform partners on their plans for ESSA implementation. Respondents represented legislatures, state departments of education, state boards of education, governors’ offices, and advocacy organizations from over thirty states. Among other questions, we asked them which supports and interventions they anticipated their states would provide to identified schools.

Disappointingly, most of our partners expect that their states will rely upon interventions like implementing instructional reform or replacing school staff. These tend to be politically easier but have proven less effective in changing outcomes for students stuck in low-performing schools.

Such tepid approaches to school turnaround are perfectly permissible under ESSA. The new federal law gives states very wide breadth to allow districts and schools to determine their own interventions for identified schools. A close read of the law reveals that states must only do the following:

- Notify districts of schools identified for comprehensive support and improvement. [Section 1005(d)(1)(A)]

- Approve and monitor district improvement plans. [Section 1005(d)(1)(B)(v)-(vi)]

- Review resource allocation and provide technical support for school improvement. [Section 1005(d)(3)(A)(ii) and (iv)]

- Set exit criteria. If the exit criteria are not met within a state-determined number of years, take “more rigorous state-determined action.” [Section 1005(d)(3)(A)(i)]

In short, the federal law does not require that states do much of anything about identified schools. This is quite clearly a response to the federally prescribed cascade of sanctions that were forced upon states under No Child Left Behind’s School Improvement Grant (SIG) program, which demonstrated only mixed results for schools despite receiving billions in federal funding.

But take heart, reformers! The lack of federal requirements does not mean that states must sit on their hands. In fact, when combined with existing state authority, ESSA gives ambitious states more than enough tools to make radical changes for students who are languishing in identified schools. Another close perusal of ESSA clarifies that states have the option to:

- Distribute the 7 percent Title I set-aside for school improvement to districts via competitive grants instead of formula grants. [Section 1003(b)(1)(A)]

- Set aside an additional 3 percent of Title I dollars to be distributed through competitive grants to districts serving low-performing schools to provide direct student services. [Section 1004]

- “Take additional action to initiate improvement” in districts serving a significant number of low-performing schools. [Section 1005(d)(3)(B)(i)]

- Establish alternative evidenced-based strategies that can be used by districts. [Section 1005(d)(3)(B)(ii)]

At ExcelinEd, we are hopeful that many states will step up to the plate and use their newfound flexibility to do something dramatic: harness the power of parental choice and help turn around their lowest-performing districts and schools.

So what might that look like?

An ambitious state could distribute the 7 percent school improvement funds through competitive grants—rather than passing them straight through to low-performing districts as formula funds— incentivizing districts to implement robust public school choice programs that extend preference to students in the lowest-performing schools. Then, using the additional 3 percent set-aside for direct student services, the state could incentivize those same districts to provide transportation for their school choice programs and/or provide needed remedial or advanced courses through a state course access program. (Check out my colleague Neil Campbell’s entry, to be posted tomorrow, for more on that!)

Next, an ambitious state could set rigorous exit criteria for identified schools (e.g., a school must increase its school rating at least one level within three years). If the criteria are not met, the state could give the district an option of closing the school altogether (and ensuring that those students are giving priority admittance to a nearby high-performing school) or closing the school and reopening it under a charter management organization (CMO) with a proven record of improving student outcomes in traditionally underserved areas.

Of course, for these charter strategies to succeed, the states must have an adequate supply of high-performing charters that are motivated to take over identified schools and/or open new schools in districts with substantial numbers of identified schools. In the past, most CMOs have been hesitant to get involved with school turnaround (see, for example, the SIG program’s first year, when just 6 percent of schools used the “restart” model).

Some states will already have enough willing, high-quality homegrown charters; some states can adopt policies that allow great educators to open their own homegrown charters; and other states will have to establish additional state-level policies that will attract high-performing charters. For example, a state could lift any state or district cap on the number of charters; streamline the authorization process for high-performing CMOs; ensure that CMOs have adequate autonomy to select their own staffs, administrations, curricula, and school cultures; provide public facilities assistance (through buildings or financial support); and help charters gain access to start-up funds.

So, will states step up to the plate on school turnaround? We certainly hope so. But our disappointing survey results indicate that state and federal advocates have a ton of work to do to help states understand their authority under ESSA—as well as their responsibility to take dramatic action on behalf of our students, who have been failed by their schools for too many years.

Claire Voorhees is the director for K–12 reform at the Foundation for Excellence in Education.