Editor’s note: This is part two of a three-part series. Part one examined possible causes. This was first published on the author’s Substack, The Education Daly.

Last week, we ran through the many possible explanations for the rise in absenteeism. They come in all shapes and sizes, some more plausible than others.

This time, I’d like to unpack how this issue plays out in cities and suburbs. It’s no secret that the pandemic has caused the biggest expansion of academic inequity in generations. One might presume the same thing happened with absenteeism—that is, the effects were felt most by the lower income families that always seem to receive the short end of public services. But what stands out most is how kids are missing school everywhere.

Let's start with Oakland

You probably know already that chronic absenteeism is epidemic in our big cities.

The numbers are depressing and have been widely reported. New York City’s chronic absenteeism rate hit 41 percent in 2021–22. Los Angeles was 45 percent. In Detroit—and it’s hard to believe this is not a typo, I know—it was 77 percent. Google any major district and you’ll find a similar headline.

I am particularly interested in the Oakland Unified School District, partly because it has a comprehensive and highly transparent dashboard detailing attendance patterns for more than a decade. (Good job, OUSD!)

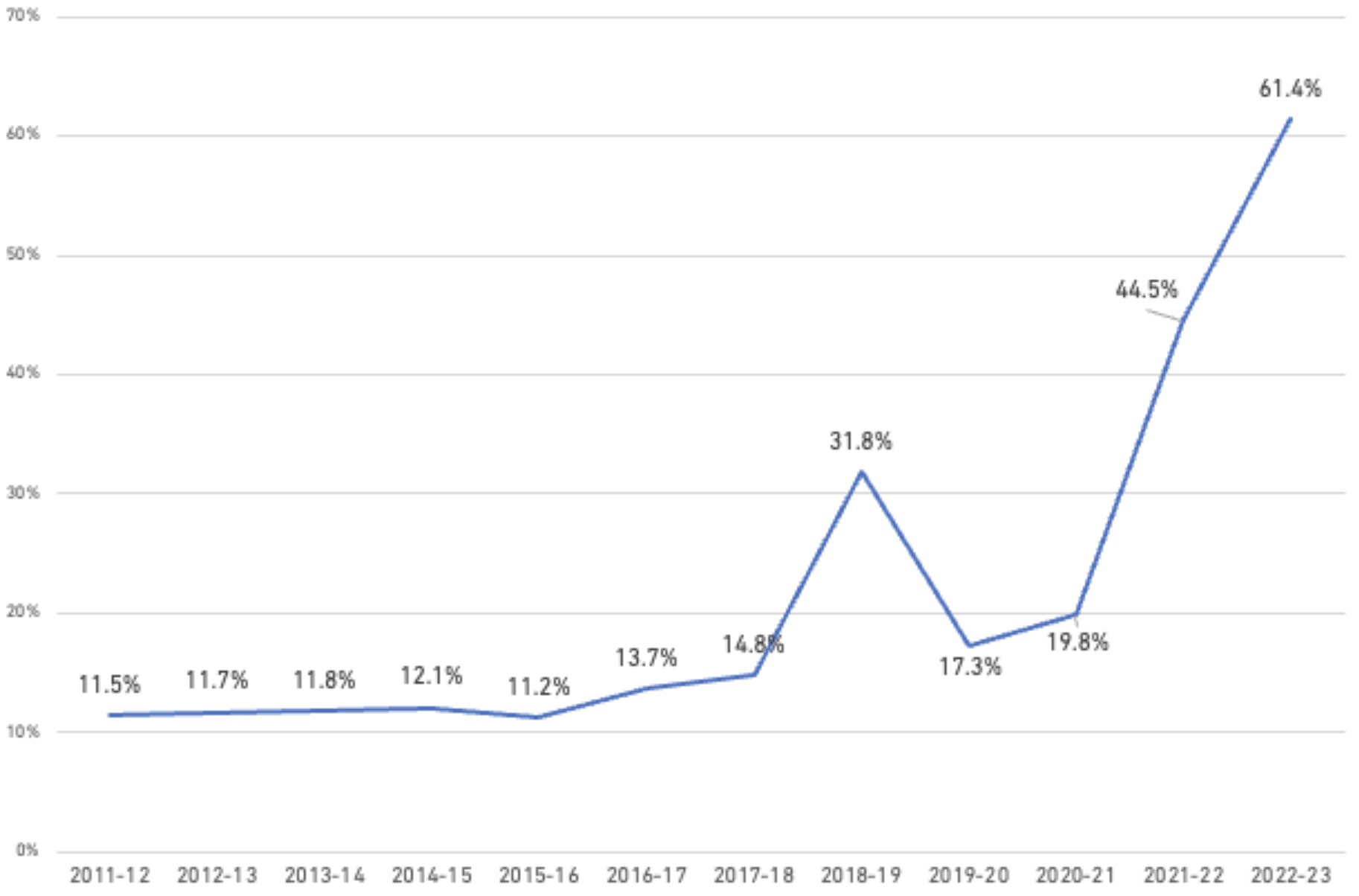

I organized the data from 2012–23 below:

Figure 1. Percentage of OUSD students chronically absent by year, 2012–2023

Source: Oakland Unified School District, Dashboards, Attendance Group Snapshot, retrieved from https://dashboards.ousd.org/views/ChronicAbsence_0/Comparison?:embed=y&:display_count=no&:render=false#40

Overall, 61 percent of Oakland kids were chronically absent in the most recent school year, 2022–23. While rates were concerning across the board, figures were higher for Black and Latino students (70.5 and 67.2 percent, respectively) than for White and Asian students (47.8 and 35.6 percent). This is consistent with trends elsewhere. Students of color often face heightened barriers to regular attendance.

The real shocker is how much chronic absenteeism has grown for all students in the past decade. In 2011–12, the first year tracked on OUSD’s dashboard, only 11.5 percent of all enrollees missed 10 percent or more of school days. As you can see from the graph, levels remained pretty steady for a number of years. But by 2017–18, they began to climb noticeably. There was a major surge in 2018–19—before the pandemic—to almost 32 percent.

While absenteeism appeared to drop in 2019–20, that was the year the pandemic arrived. Schools were entirely closed from March onward. Attendance tracking was understandably wonky. (Read: generous.) As schools reopened for in-person learning full time, absenteeism went through the roof.

The new normal is more missed school for every subgroup. For example, White students in Oakland today are chronically absent at a much higher rate than was the case for Black students eleven years ago.

Same district. Minor demographic changes over a decade but nothing revolutionary. How did Oakland go from approximately 12 percent chronic absenteeism to 61 percent? And how on earth will efforts to address lost learning such as increased mental health support and high dosage tutoring make any difference when a majority of the district’s students miss an average of one day of school every two week—at a minimum.

I wonder whether Oakland will ever regain its levels of school attendance from a decade ago. It’s hard to be optimistic.

Just as an example, the district cut the positions of five attendance officers prior to the 2022–23 school year. What? Then it weathered a teacher strike, and absenteeism got worse.

What about the suburbs?

It’s true that chronic absenteeism is more acute in low-income communities where evictions, homelessness, and isolation from health care and social services are widespread. That’s a story we know well. Always been that way. But if economic inequity is the sole driver of today’s absence epidemic, someone needs to explain what’s happening on Chicago’s North Shore.

New Trier Township High School serves some of the wealthiest suburban communities in the country, including Wilmette, Kenilworth, Winnetka, and Glencoe. Nearly 90 percent of the study body is White or Asian. Students and families have access to incredible supports through their own resources. On top of that, the school itself is absurdly well-funded. It’s difficult to believe that a significant number of New Trier students are absent due to traditional hardships like not having transportation.

But nonetheless, they are absent in huge numbers. As reported in the Chicago Tribune last spring, 25 percent of the student body was chronically absent for the 2022–23 school year as of February 10. Most intriguingly, “the percentage of chronically absent students rose by class with just over 14 percent of freshmen, 21.4 percent for sophomores, 27.8 percent for juniors, and almost 38 percent for seniors.”

You read that correctly: Almost 40 percent of seniors at one of the nation’s most privileged public high schools had problematic attendance. A swarm of Ferris Buellers, attendance-wise. One can’t help but sympathize with beleaguered Superintendent Paul Sally, who told the Tribune “We’ve been looking at this and struggling with this in a lot of ways.”

The freshman are showing up. The seniors are not. The skew of absence patterns toward older groups is consistent with a theory that absenteeism is in significant part a social contagion exacerbated by diminishing accountability as students approach graduation with the grades and credits they need for college already secured. Kids aren’t tolerating any more high school than is absolutely necessary.

New Trier seems to see it this way. For the new school year, the school formed a committee that recommended substantially more stringent policies for absences, including a ban on participating in extracurriculars on the same day a student misses school. The board and administration are not treating absenteeism as a problem that will fix itself.

Time will tell if New Trier gets its students back in school. But credit them for acknowledging the problem publicly, defining its dimensions with transparent information to the public, and laying out specific interventions.

Districts across the country are in the same boat, searching for the best solutions.

So what did we learn today?

1. For a district like Oakland, this is not a matter of a post-pandemic rough spot. Absenteeism was already rising before Covid. There’s a deeper thing going on. And the bottom line is: More than five times as many Oakland kids are chronically absent today compared to a decade ago.

2. Nobody should be pointing fingers at low-income parents as the root problem, as if they are uniquely unwilling or unable to get their kids to school. Plenty of students from our nation’s wealthiest families are chronically absent, too. For every demographic group, numbers have gone up. Just like with the pandemic, we’re all in this together—like it or not.

3. Districts have started to realize that the spike in absenteeism is not going to dissipate magically on its own. They are becoming more assertive with remedies.

Next week in our third (and final) installment on this issue, we will consider those remedies more carefully, parsing arguments for relying more on carrots or sticks, so to speak. I’ll offer some specific recommendations of my own.