Editor’s note: This is part three of a three-part series. Part one examined possible cause of chronic absenteeism, and part two explored how it plays out in cities and suburbs. This was first published on the author’s Substack, The Education Daly.

Key points from the previous two posts:

- Absenteeism has risen across the entire U.S.—all fifty states.

- While the pandemic was a massive accelerant, chronic absenteeism was already increasing before anyone had heard of Covid.

- There are many different explanations for what’s behind the absenteeism crisis and relatively little consensus about which ones are most responsible.

- All types of kids are missing more school than before—wealthy, poor, urban, suburban.

Today, it’s time for solutions.

—

I desperately want our kids—all of them—back in school. Unless student attendance improves, any efforts to address pandemic learning loss are doomed to fail. Let’s start there. Struggling students will fall further and further behind. Moreover, if we aren’t willing to expect students to show up for school, what are we willing to expect from them?

Yet current strategies are a patchwork of local initiatives that aren’t making much of a difference. At this rate, it could easily take a decade to bring chronic absenteeism back to pre-pandemic levels—and to be clear, those levels were already problematic in many places.

Here are my five recommendations.

#1. Distinguish between chronic absenteeism and school avoidance

A key first step is clarifying the degree to which we’re dealing with situations where students can’t get to school versus situations where they won’t go. The solutions for those two scenarios are very different.

In a brief published this year, Attendance Works and The Education Trust argue that punitive responses—civil penalties like tickets and fines, as well as school-level measures like exclusion from extracurricular activities—are ineffective. They call for tiered supports aimed at making schools physically and emotionally welcoming places where students will feel a sense of belonging.

It’s hard to be against any of that. Surely many students are missing school because they have become disconnected. But if you look into best practices for addressing school avoidance—the phenomenon of refusing to go to school or creating reasons not to go—they are pretty different, and they definitely include some things that verge on punitive.

For instance, check out a list of tips from the American Academy of Pediatrics. Keep discussions about physical symptoms or anxieties to a minimum. If your child is well enough to be up and around the house, they are well enough to go to school. If a child stays home, do not offer any special treatment. No visitors. No appealing snacks. This is coming from doctors.

Harvard Medical School goes even further by counseling parents to “make staying home boring” so it’s not a preferable option to attending school. Take away all screens. No sleeping or lounging unless a child is genuinely ill.

The underlying message here is that if staying home playing video games and scrolling through social media platforms in pajamas is an option, plenty of kids are going to take it. They’re kids. Were you any different at their age? There’s only so much schools can do to make themselves appealing. Combatting school avoidance starts with a commitment to “be firm” about the imperative to be in school.

After wading through all of this, I suspect school avoidance is a meaningful contributor to our surge in chronic absenteeism. We should acknowledge it and develop specific solutions that address it just as we address other problems like bus driver shortages.

#2. Learn from employers

We educators are not alone. Companies have seen the same challenges when asking their workers to give up the flexibility of remote/hybrid routines and return in person to their offices. It started with assurances about robust health precautions. That didn’t fill any cubicles. Bosses moved on to a comical sequence of incentives—many outlined in a Slate piece from Sept 2022—such as coffee, breakfast, hot pretzels, Red Bull, puppies, cornhole tournaments, and booze. When all those failed, they tried soft mandates that were enforced not at all or selectively enforced based on the perceived difficulty of replacing the employees who balked.

But the social fabric of workplaces had changed. Working from home had become normalized among employees and valued for the ways it made life easier for working parents and former commuters. Some of those who heeded the early calls to return to the office felt like dupes when they realized many of their colleagues weren’t coming back and faced no consequences for refusing to do so. White collar workers became rebels against badging in.

Eventually, employers figured out that carrots needed to be supplemented with sticks. Over the course of 2023, mega-companies like Disney and Amazon have mandated time in the office. Others, like Google, have warned of low performance evaluations for those who don’t comply with guidelines for in-person work. As the New York Times told us recently, even Zoom is cracking down.

Doesn’t this sound an awful lot like what happened with schools? First, nobody was allowed to attend in person. Then assurances were given that it would be safe to attend, but wide accommodations were made for those who weren’t comfortable or whose vulnerabilities made it dangerous for them to be in person. Over time, schools tried to lure back reluctant learners with welcoming environments, parties, and incentives. But the norms about attendance had clearly changed. Any stigma related to missing school was gone. Some students weren’t willing to attend regularly, and both they and their parents figured out that there weren’t many consequences for absenteeism.

My specific recommendation here is to treat consistent attendance as a social norm that needs to be named, supported, and reestablished. Stop hoping kids will attend regularly and begin insisting on it. Be understanding with those families who face genuine barriers—but those cases are the exception. The vast majority of kids can be in school more than 90 percent of days. How do we know? Because a decade ago, students were chronically absent far less often.

#3. Stop enabling absenteeism

I’m conscious of not painting with too broad a brush, but some schools have absolutely perpetuated the absenteeism problem with lax policies and minimal enforcement of them. Things like:

- Allowing students to participate in extracurriculars, sports, and leadership activities if they attend any part of a given school day—even half of one period.

- Unlimited retakes of quizzes and tests at any time during the grading period.

- Unlimited time to make up work missed during absences.

- No caps on the number of unexcused absences a student can have and still receive credit for a course.

- Pressuring parents to keep their kids home with any sniffle, however small.

- Excused absences for “mental health days” without any requirement to have seen a mental health professional or received a diagnosis.

In light of our predicament, do these things seem wise? Absences are a part of school life and always will be. But if students can miss school as often as they like with virtually no downside, they are going to miss a lot of school. (And their parents are not likely to tell them they can’t.)

#4. Adopt affordable, research-tested practices

There are practical things districts can do. Todd Rogers is a Harvard behavioral scientist who has done innumerable experiments testing light-touch absenteeism interventions. In a 2018 paper, he found that parents often believe their children have missed school far less often than is the case. When repeatedly provided with printed information about the true number of days their child has been absent, guess what happens? Families get their kids to school more often. It’s just a day here, a day there—but those days quietly add up. This kind of intervention doesn’t solve the whole problem, but it’s cost-effective and easy to execute. He started EveryDay Labs to help districts implement their own initiatives. The company now delivers millions of absence-reduction communications to families each year. Letters home are far less punitive than prosecuting the parents of kids with too many unexcused absences, as Missouri has done and Texas is considering.

Your local district got piles of federal money to combat the effects of the pandemic. Do you know if its leaders used any of it to send carefully crafted letters to the parents of kids who are missing school?

#5. Be honest and direct with parents

Despite all schools can do, attendance is far more dependent on factors related to parents and students. They are the ones who set alarm clocks. At parent-teacher conferences, in weekly bulletins, at bake sales, and during morning drop-off, here are some key messages that can’t be repeated by school leaders frequently enough:

- Missing school regularly is not healthy for your child. This is probably the number one thing we learned during the pandemic. In-person school works.

- Your child should be absent as rarely as possible and not more than ten times in a full school year.

- Allowing your child to miss school without a genuine reason—like illness—that prevents attendance is not understandable or OK.

- States mandate school attendance for kids, with good reason. If your child misses excessive numbers of unexcused days, we are mandated as a district to report it, and you may get a visit from a social worker.

- If your child has trouble getting moving in the morning, you need to take steps as a parent to address it. Put supports in place like an early, reliable bedtime, no devices (phones, tablets, video games, TV) in the bedroom overnight, and a step-by-step wake routine.

- If your child is missing days because of issues in our control as a school—things like buses being late or not running, bullying on the playground, etc.—let us know, and we won’t rest until we’ve addressed it.

Parents want to be part of the solution. So many of them fell out of the habit of daily attendance during the pandemic. Now they can’t figure out how to re-establish it. Let’s help them.

A colleague shared a great practice her child’s principal is using. Each week, the principal emails data on school-wide attendance and a breakdown for each grade. Easy, inexpensive, and smart. More, please.

It’s time to exit our Ferris Bueller phase

I can’t tell you how many parents have contacted me during this series to share their own stories and struggles. It’s hard.

As a country, we transitioned to at-home learning in March 2020, and in critical ways, we’ve never transitioned back. It’s time to leave behind some of the new pandemic habits we picked up because they are no longer necessary or healthy. While students may argue that they can learn just as much from home as in school, piles and piles of evidence tell us this is not so. When kids don’t show up for school, they fall behind.

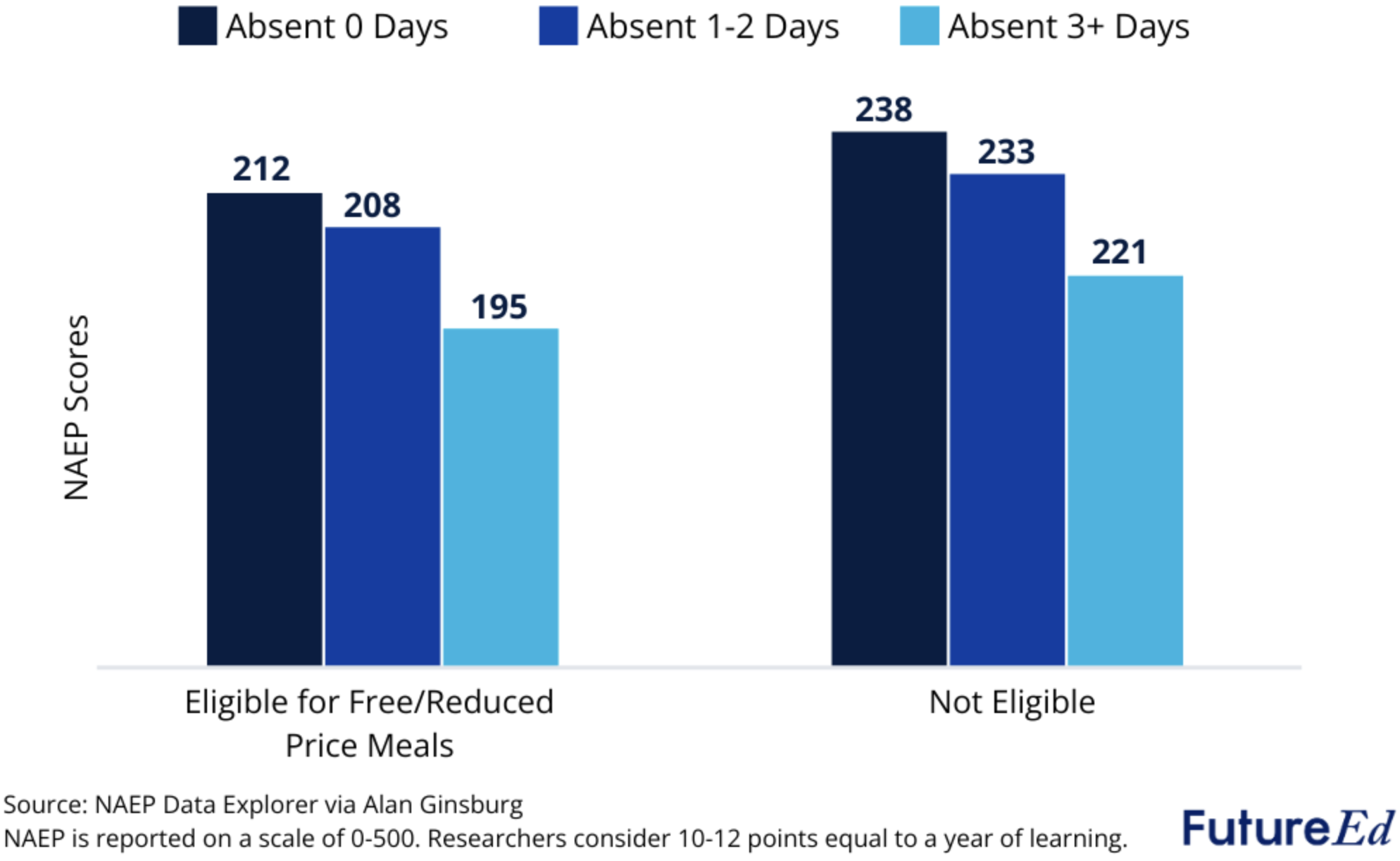

As long as chronic absenteeism remains normalized, we will not reverse the massive drops in achievement that have occurred in the past decade. In fact, a new analysis by FutureEd (see a figure from it below) suggests that missed school might be one of the driving factors behind lower test scores, which would explain why even states that returned to in-person learning sooner, such as Florida and Texas, still saw their performance levels decline. They won the battle to re-open. They lost the battle against chronic absenteeism.

Figure: NAEP fourth-grade reading scores by test-takers’ days absent in the prior month, 2022

So let’s get serious. Ferris Bueller’s attendance philosophy used to be called “senioritis.” In 2023, we’ve caught a scorching national case of senioritis—as parents, as educators, as students, as policy leaders, and as elected officials. Our senioritis is epidemic. If we don’t start curing it, it will be a form of long Covid that shapes a generation of kids who have endured enough already.