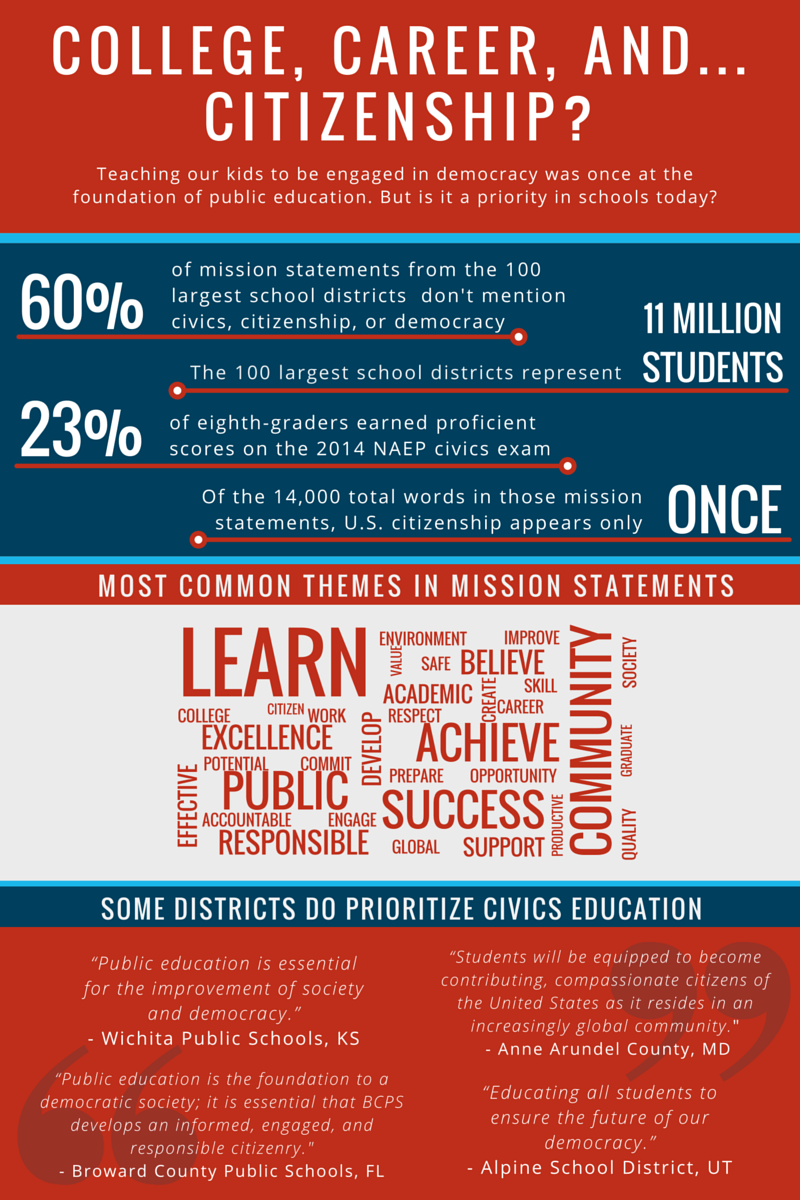

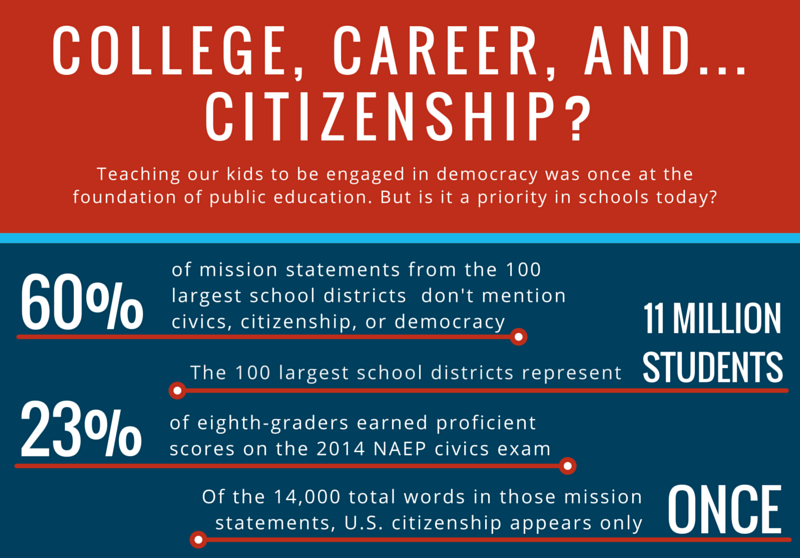

Tomorrow is Constitution Day, when all schools receiving federal funds are expected to provide lessons or other programming on our most important founding document. But when only one-quarter of eighth graders score “proficient” on the most recent NAEP civics exam, it’s also a reminder of how rarely civics and citizenship take center stage in America’s public schools.

The public-spirited mission of preparing children for self-government in a democracy was a founding ideal of America’s education system. To see how far we have strayed from it, Fordham reviewed the publicly available mission, vision, and values statements adopted by the nation’s hundred largest school districts to see whether they still view the preparation of students for participation in democratic life as an essential outcome. Very few do. Well over half (fifty-nine) of those districts make no mention of civics or citizenship whatsoever in either their mission or vision statements.

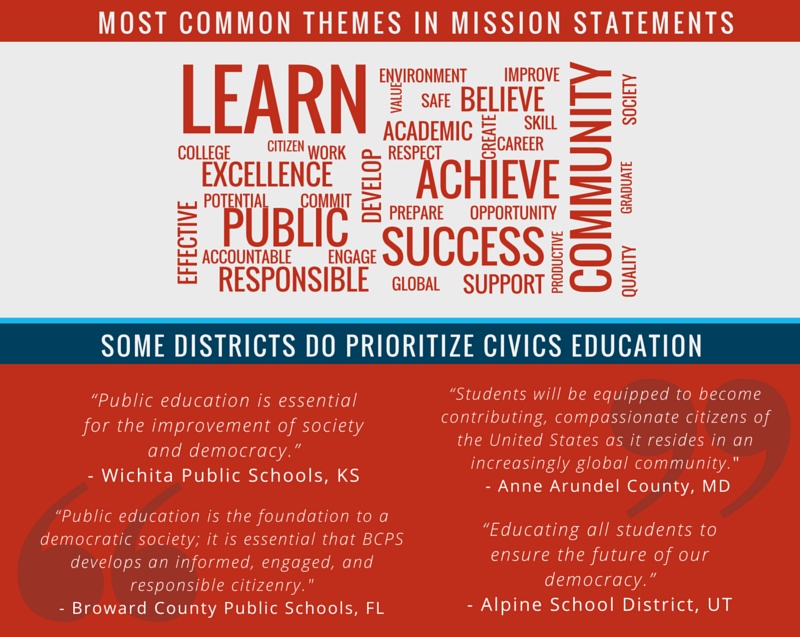

The personal and private reasons for education—preparation for college and career, for example—are much more on the minds of school district officials who write and adopt these statements and goals than the public virtue of citizenship. The words “college” (thirty-seven occurrences) and “career” (forty-six), for example, easily outnumber “civic” (eight) and “citizen” (twenty-eight). For comparison, the most commonly occurring words are, unsurprisingly, “student” (433), “school” (250) and “learn” (175).

The fourth-most-used word, “community” (141), could be viewed as a proxy for citizenship. However, that term most frequently occurs in bromidic phrases like “community of learners,” or refers to what the community can do for students rather than what the students are expected to do for the community. The San Diego Unified School District mission statement, for example, includes this phrase: “Engages parents and community volunteers in the educational process.” Nurturing a supportive community is not a bad goal; it’s simply not the same as preparing students for active participation as citizens.

To be sure, some districts’ mission statements demonstrate a clear focus on preparing students for citizenship, or establish it as an equal priority with more personal goals:

- “Public education is the foundation to a democratic society; it is essential that BCPS develops an informed, engaged, and responsible citizenry.” (Values, Broward County Public Schools, Florida)

- “We believe that public education is essential to the survival of a democratic society.” (Beliefs, Henrico County Public Schools, Virginia)

- “Public education is essential for the improvement of society and democracy.” (Shared Beliefs, Wichita Public Schools, Kansas).

- “To provide an education and the supports that enable each student to excel as a successful and responsible citizen.” (Mission, Hillsborough County Public Schools, Florida)

By contrast, Montgomery County, Maryland, doesn’t even acknowledge a civic role. Its mission statement reads, “Every student will have the academic, creative problem solving, and social emotional skills to be successful in college and career.” Neither is there any mention of civics or citizenship in the vision statement or the district’s “core purpose,” which is this: “Prepare all students to thrive in their future.”

Unsurprisingly, a substantial number of mission and vision statements are either meaningless homilies or bland statements seemingly calculated to be inoffensive.

- “FBISD exists to inspire and equip all students to pursue futures beyond what they can imagine.” (Mission, Fort Bend Independent School District, Indiana)

- “The mission of the District School Board of Pasco County is to provide a world class education for all students.” (Mission, Pasco County Schools, Florida)

- “With a caring culture of trust and collaboration, every student will graduate ready for college and career.” (Mission, Atlanta Public Schools, Georgia)

- “Omaha Public Schools prepares all students to excel in college, career, and life.” (Mission, Omaha Public Schools, Nebraska)

Some terms are conspicuous in their absence. The words “patriotic” and “patriotism” do not appear at all in any of the hundred districts’ public statements that we reviewed. Only two districts—Wichita Public Schools in Kansas and Utah’s Alpine School District—include the word “democracy” (Eight mention the word “democratic.”). Maryland’s Anne Arundel County is the only district that specifically mentions U.S. citizenship in its mission or vision statement. (“Students will be equipped to become contributing, compassionate citizens of the United States as it resides in an increasingly global community.”) Perhaps most surprising of all: The words “America” and “American” appear in none of the hundred mission and vision statements. However, “global” appears in the statements of twenty-eight districts—usually in phrases like “global society,” “global economy,” or “global citizens.”

In fairness, a district’s mission statement may not offer much insight into the nature of its instructional practices, the civic values that are communicated to students, or the full range of outcomes sought by each school system. But at some point, leaders and stakeholders in each district sat down and attempted to craft and approve a set of ideals, values, and goals that ostensibly reflect the aspirations of their communities. Thus mission statements offer a window into our evolving view of the purpose of education.

The mission statement of the Alpine, Utah, school district, which serves twelve municipalities outside Provo, is a good example. It was approved by its board of education in 2003 and places a premium on “educating all students to ensure the future of our democracy.” A set of goals adopted more recently includes “civic preparation and engagement.” District administrator David Stephenson says that the mission “is aligned with what we do in the classroom. We obviously follow state core curriculum civics instruction. We follow state law on what we teach. It’s really aligned well with that curriculum.”

“The mission statement is not made by random people on a Tuesday afternoon. It’s the community, building principals, school administrators, parents, teachers, superintendents. All of our adult stakeholders were represented in crafting a mission that best represents our community,” says Andy Jenks, a spokesman for Henrico County Public Schools in Virginia. “We do think it’s important. In some cases it might be the first thing somebody reads about our organization.”

The National Assessment of Educational Progress lists five dispositions it says are “critical to the responsibilities of citizenship in America's constitutional democracy.” These are active, not passive roles: respecting human worth, responsible participation, promoting a healthy democracy. If these aren’t priorities of a school district, are they priorities of their students? The data says no. Of the eighth graders who took the NAEP’s civics exam in 2014, only 23 percent scored proficient marks.

If a school districts’ mission and vision statements are any indication, such uninspiring results are also unsurprising. They simply mirror the priorities established at the local level for K–12 education, where preparation for citizenship is not a high priority.

On Constitution Day, it’s worth asking whether it is time to restore the public mission of public education to its rightful status as a priority for our schools.

Robert Pondiscio is Fordham’s vice president for external affairs. Kate Stringer is an editorial intern.

___________________________________

Download the full infographic: