It should be great news: Graduation rates for Minnesota’s black and Hispanic students—which have long lagged the rate for white students—are on the rise.

But how much do these new graduates actually know? What skills have they mastered? In other words, what is their high school diploma really worth?

MinnPost.com recently profiled a new “Spanish Heritage” program at Roosevelt High School that Principal Michael Bradley credits with helping to boost the school’s Hispanic graduation rate by about fifteen percentage points in 2015. The program features “culturally relevant pedagogy” and focuses on developing Hispanic students’ sense of “cultural identity.”

What precisely do students learn in the Spanish Heritage program? The article explained that students “see themselves in the curriculum,” “find their voice,” and “become their own advocates.” But it says little about whether they acquire the knowledge and skills necessary to become well-informed, productive citizens.

Why is this important? In searching the Minnesota Department of Education’s website, I discovered a disconcerting fact: Though Roosevelt’s Hispanic graduation rate increased to almost 75 percent in 2015, only 6 percent of the school’s Hispanic students were proficient in reading and only 10 percent in math, as measured by state tests.

MinnPost’s profile concluded with a student poem whose tone struck me as profoundly alienated. What is the “culturally relevant pedagogy” that contributed to such a negative cultural identity?

A pedagogy of opposition

Culturally relevant pedagogy is the brainchild of Gloria Ladson-Billings, a professor of education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She coined the term in 1992 and says that it describes “a pedagogy of opposition.” A primary goal of her approach, she says, is that “students must develop a critical consciousness through which they challenge the status quo of the current social order.”

Ladson-Billings singles out Paulo Freire as an author whose vision of education undergirds culturally relevant pedagogy. Significantly, the Roosevelt student's poem names or quotes Freire no less than five times.

Freire was a Brazilian activist and educator who worked with disenfranchised Latin American peasants in the 1950s and 60s. In his 1968 book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, he taught that all societies are divided between “oppressors” and “oppressed” and called for the revolutionary overthrow of capitalist hegemony. Freire dismissed academic learning as mere “official knowledge” that oppressors use to rationalize inequality in capitalist societies. How does a pedagogical approach grounded in such a perspective prepare American students for success in 2016?

Today, many educators assume that black and Hispanic students cannot succeed in school unless they “see themselves in the curriculum.” But great thinkers of the past had a very different view.

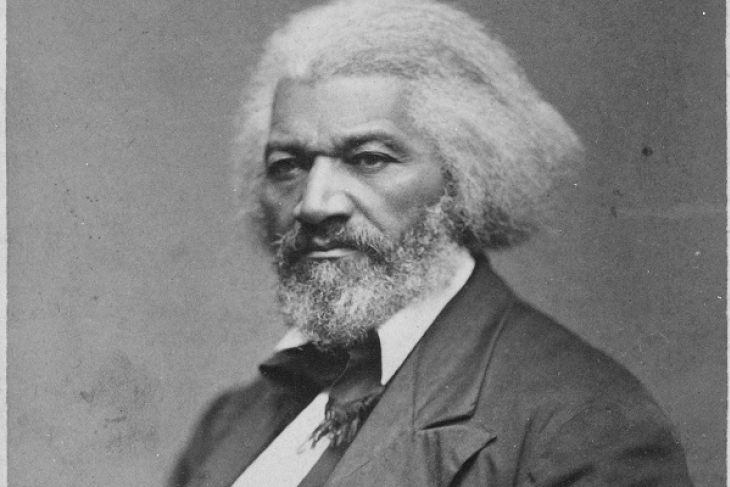

Douglass, Du Bois, and Addams

Take Frederick Douglass, America’s great anti-slavery orator and crusader. Douglass, a former slave, wrote that it was a parliamentary speech by white, Irish playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan that equipped and inspired him to launch his anti-slavery crusade. Sheridan’s mighty speech “gave tongue to interesting thoughts of my own soul, which had frequently flashed through my mind, and died away for want of utterance,” wrote Douglass. The reading of Sheridan’s “powerful vindication of human rights” enabled him “to utter my thoughts and to meet the arguments brought forward to sustain slavery,” he said.

W.E.B. Du Bois, another great black social reformer, voiced a similar conviction in The Souls of Black Folk in 1903. “Can there be any possible solution” to the challenge of black social advance “other than by study and thought and an appeal to the rich experience of the past?” he asked. Du Bois drew inspiration from thinkers ranging from Shakespeare and Aristotle to the French novelist Balzac. “So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the Veil,” he wrote. “Is this the life you grudge us, O knightly America?”

The social reformer Jane Addams, founder of Chicago’s Hull House, employed Douglass and Du Bois’s vision of education as “the best that has been thought and said” to lift destitute immigrant children into the American mainstream in the early twentieth century.

Addams would have disdainfully rejected the notion that the key to keeping her poverty-stricken Sicilian and Bohemian pupils engaged in school was to immerse them in a study of their ancestors’ cultures. Hull House, she wrote, was “a protest against [this] restricted view of education.” Instead, Addams expanded her students’ minds by teaching world history, botany and “the great inspirations and solaces” of history’s “literary masterpieces.” Thus equipped, those young people went on to fulfill the promises of a better life that had drawn their parents to America.

A worthy successor

Cristo Rey High School in Minneapolis is a worthy successor to Addams’s Hull House. The school is one of thirty Jesuit high schools throughout the nation that serve low-income students, primarily Hispanics.

Cristo Rey is a “college and career preparatory school” whose students must pass challenging standards-based tests in reading/literature, math, history, and science to advance from one grade to another. The school does not seek to develop in its students a “cultural identity” that sets them apart from other Americans. On the contrary, students attend class four days per week and work one day per week at a company—including General Mills, Allianz Life, and Cargill—to earn money to pay their tuition and develop valuable, marketable skills. Every member of Cristo Rey’s class of 2015 has been accepted to college.

“Culturally relevant pedagogy” may be well-intentioned. But its multicultural vision prevents minority students “from utilizing the existing culture of the larger society around them for their own advancement,” in the words of black economist Thomas Sowell. “Multiculturalism, like the caste system,” he points out, “tends to freeze people where the accident of birth has placed them.”

I wish the students of Roosevelt’s Spanish Heritage program well. But I can’t help wishing they had the opportunity to attend a school that—instead of locking them in the box of “culturally relevant pedagogy —equipped them with the knowledge and skills they need to seize the opportunities that wait at their doorstep in America.

Katherine Kersten is a senior fellow at Center of the American Experiment.

Editor's note: This article originally appeared in a slightly different form at MinnPost.