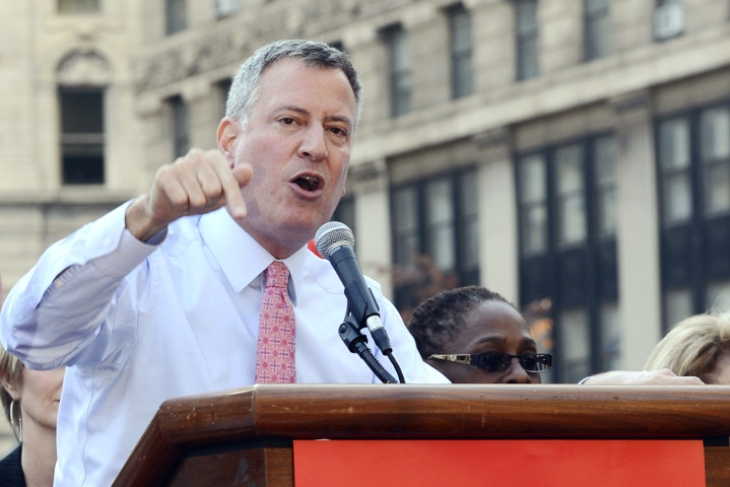

Bill de Blasio’s public-education agenda consists of seven boasts (things he says he’s already done, part of his record as public advocate) and nineteen plans for future changes (“policies, agendas, and programs” that he promises to “work tirelessly to implement”). Minus the overlap, they add up to two dozen ideas. Here’s how I score them:

Potentially worthwhile, but over-the-top or unaffordable: These five notions include his preschool promise. The problem? Preschool could do considerable good for some very needy kids, but the universal version he’s espousing is a costly, unnecessary windfall for hundreds of thousands of middle-class parents and apt to result in a program that’s too skimpy to really benefit the children who need it most. (Note, too, that the city’s current pre-K programs are under-enrolled.)

Much the same can be said for universal after-school programs for middle schoolers, considering that plenty of parents already have this worked out. A serious education reformer would instead expand learning time by lengthening the school day and year. But the unions won’t like that.

As for universal school breakfasts and arts education, believe it or not, a lot of kids really do get fed before leaving for school, and art, worthy as it is, mustn’t crowd out the three R’s before children have mastered them.

Overdue reforms (if he puts teeth in them): I count two here.

Getting every child to read by third grade is a grand ambition that’s unlikely to be met unless there’s a “promotional gate” barring entry into fourth grade for those still illiterate. The same for improving special education to focus more on results for disabled youngsters. It’s much needed but unlikely to happen if the “improvement” consists entirely of more inputs. Where’s the results-based accountability? And the willingness to take on obsolete federal special-ed rules?

Potentially sound ideas: This covers six of his pledges.

One is placing less reliance on single test scores, whether for judging schools and teachers or admitting students to selective programs. But determining what other factors to weigh—and how to do so fairly, rigorously and affordably—is no walk in the park.

Similarly, fixing bad schools rather than closing them is a noble aspiration, but one that nobody in the land has figured out how to do in a reliable, replicable way. Far better to open a new and different school (maybe a charter) in the building formerly occupied by the one that failed.

As for “expanding and improving career and technical education,” the whole country should do that, but what exactly does he have in mind? Likewise “placing great leaders” in every school—and then empowering them to lead those schools. The key is to give building-level leaders real power to make decisions about personnel—who to hire and fire, where they’re deployed and how they’re paid—which would drive the unions bonkers.

More harm than good: This covers his call for across-the-board class-size reduction, which boils down to hiring more teachers (impossible to do while also improving their quality), building more facilities (very slow), and spending tons on a strategy that much research shows to be hugely expensive and rarely effective in boosting student achievement.

Also damaging are his plans to make it more difficult for charter schools to operate in city facilities. This would seriously damage one of the Bloomberg era’s signal education accomplishments.

Fluff: This covers nine bits of crowd-pleasing campaign rhetoric that’s essentially impossible to turn into anything serious. Thus, he has sundry proposals to “involve” or “give voice” to various constituencies, vague plans to “improve mayoral control” and “strengthen citywide oversight” of the education system, nebulous musings about “bullying” and “strengthening school safety” and big promises (uttered by many across the land) to beef up “college and career readiness.” Surely a fine impulse but nothing even faintly akin to an actual program.

This kind of stuff may have helped him win Tuesday, but it’s no battle plan for conquering ignorance with strategies and weapons that the nation’s biggest city can plausibly mobilize, pay for, and deploy.

De Blasio would’ve done more to persuade education reformers that he’s serious if he’d dispensed with twenty-four-point agendas and, instead, said who he plans to hire as schools chancellor.

A slightly different version of this article originally appeared in the New York Post.

This piece was updated on November 7, 2013, for inclusion in the Education Gadfly Weekly.