After roughly a year of presidential politicking during which education has been given short shrift, two primary debates over the past few days have restored the issue to news cycle relevance. Both were held in troubled Michigan cities in advance of today’s crucial primary. It’s not clear what about the state suddenly brought public focus back to K–12 schooling, but there’s undeniably something in the water.

During last Thursday night’s Republican conclave in Detroit, Fox moderator Megyn Kelly asked John Kasich the first substantive question on education posed to any GOP candidate in over half a year. (Jeb Bush was queried on Common Core at the very first debate, held in August.) The Motor City’s schools are burdened with billions in debt, Kelly said, and kids are often forced to study in filthy, unsafe classrooms. Should the next president intervene with a windfall of federal cash, as the present one did with the auto industry?

It’s to Kasich’s credit that he gave a reasonably germane and detailed answer, especially given the rhetorical bloodbath being waged to his right. The governor drew a comparison between Detroit’s public schools and those in Cleveland, a similarly blighted district that has made some strides during his time as governor. He added some details about his general educational platform, dropped in a few nice words about local control, and bathed in the crowd’s polite applause.

Now, it’s fair to observe that the governor didn’t actually answer Kelly’s question, which was whether his administration would consider bailing out the Detroit school system. No one else on the stage picked up the line of inquiry, although Hillary Clinton made a credible effort at CNN’s weekend debate in Flint. Prodded by an audience question from the parent of a Detroit student, the former secretary of state vowed to revive a ‘90s-vintage federal bond program to repair and modernize school buildings. That would be a good first step, since the city’s dilapidated facilities are a national disgrace. Tellingly, though, Clinton didn’t address the broader problem of Detroit’s crushing debt crisis.

Simply put, the district is watching its financial situation swiftly erode. The widely held belief is that its coffers will run dry sometime around Easter. The schools’ emergency manager, Darnell Earley, just stepped down amid heated criticism of his performance. Steven Rhodes, the retired federal judge who oversaw Detroit’s bankruptcy proceedings, is stepping into the role, and he’s already announced that the district can’t move forward in paying down its debts until the state legislature passes some kind of aid package. Meanwhile, hundreds of teachers have been staging “sick outs”—a form of silent strike in which employees coordinate their sick days and leave the school undermanned—to protest their scandalous working conditions.

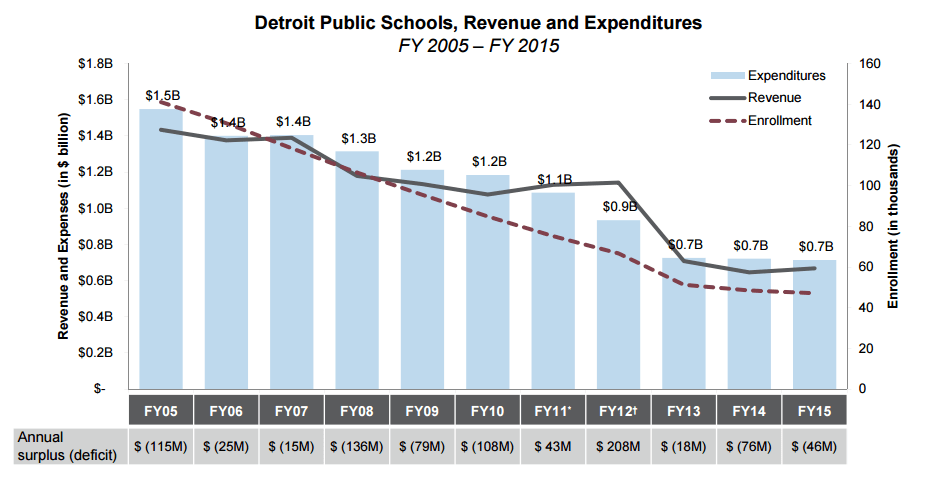

If Kasich and Clinton didn’t fully speak to these issues, they’re in good company. Nobody else has been able to offer satisfactory solutions, so why should they? The educational catastrophe in Detroit didn’t come together overnight, and the facts on the ground are stark: In the last decade, Detroit Public Schools has lost two-thirds of its students. One hundred fifty of its schools have closed, and some ten thousand jobs have been eliminated. But costs still run ahead of revenues, no matter how tightly the belt is drawn.

Source: Detroit Public Schools, “Shaping the Future,” November 2015.

With trends this ugly, it’s no wonder that DPS has become a cautionary tale. And I don’t mean that as a figure of speech; Fordham literally referred to the tragic example of Detroit in its report from last year, Who Should Be in Charge When School Districts Go into the Red? We grouped the district together with those of Philadelphia, Camden, and Chicago, labeling them “too big to close”—i.e., chronically damaged systems whose sheer size necessitates long-term emergency help from state authorities. Like their counterparts in the banking sector, the only real safeguard for such structures is prevention. If we wait until colossal districts are teetering on the brink of insolvency, it’s already too late, because no city could abide the abrupt closure of its entire public school system. In Detroit’s case, that’s exactly what happened. Michigan doesn’t identify districts as being “in distress” until they’re actively running deficits, even if pension obligations have been bleeding the city dry for decades.

Meanwhile, it’s not clear that even the most ambitious of takeovers could solve the underlying problem here, which is the ongoing disappearance of schoolchildren as families flee the city. As it stands, the string of appointed administrators heading up the district—Rhodes is now the fifth in the last seven years—grate on the families and employees whose lives are affected by them. The elected school board has been dismissed from above twice since 1999. The controversy is actually a microcosm for the leadership crisis facing the entire region: Cities all over Michigan, most famously Detroit, have lapsed into receivership over the past decade, and it’s an open question whether their drastic measures have improved matters. Amazingly, Earley himself—the departing DPS emergency manager—was formerly the emergency manager of Flint, whose poisoned water was a major point of dispute during both parties’ debates. Clinton called for an end to the reign of the technocrats at the Flint debate, but no one can plausibly say that matters were appreciably better under their democratically chosen predecessors.

It’s difficult to know what wisdom to take from such a prolonged and holistic miscarriage of governance. Authorities have to help major urban districts exercise fiscal prudence—that’s for sure. Michigan’s lawmakers should act to extend some fiscal relief to the district, and Detroit’s teachers should show up for work (although the ones working in partially condemned structures should obviously take great care). But is there really an answer somewhere over the horizon for the institutions in a city like Detroit, which has now been faltering for about as long as it once thrived? I couldn’t say for sure. And neither can our best politicians, even with their best intentions.