Back in September, with the presidential election and Freddie Gray’s death as backdrops, my sister organization MarylandCAN hosted 50CAN’s annual summit in Baltimore, which included a dinner at the church of one of its board members. The city’s Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood, where Gray lived and where I grew up many years ago, had been on my mind a lot during the days leading up to the trip, and I felt distant as we boarded the bus and started our ride to the church from downtown.

Baltimore is a distinct city, and it is a deeply familiar place if you have lived there. But as the bus turned onto Calhoun Street, I realized that it was familiar not because we were driving through Baltimore but because we were driving through my old neighborhood. Down the very streets I used to walk. On one side, there was the staccato of boarded-up row houses and the occasional stoop with small kids playing. On the other, the first school I attended; then the corner where I rode my bike. And, just out of sight, the little red house of my childhood—now an empty and collapsing husk.

I mentioned this, quietly, to two of the people sitting closest on the bus, and it sounded like thunder. I talk of the place often, but I don’t think any of my colleagues understood that “this” place was the one I meant: a place where the majority of houses sat vacant, a community devoid of its people—and opportunity.

An eerie calm hung over everyone, making the bright edges of the sparse conversations blunt and dull. And in my head, all I could think was: If I had to wait for this neighborhood's school system to right itself—or a “talent strategy” to be implemented, or for the central office to “right-size”—I very likely would still be sitting there, watching this bus roll by, speeding away with one of my life’s possible futures locked up in it.

Instead, a scholarship to the right school—a private school in a time before charter schools even existed—lifted me up and made my education possible. It wasn’t a reform that took years of pursuing; it was a scholarship implemented on a single day with my admission to school. I did not have to wait. Why should any child?

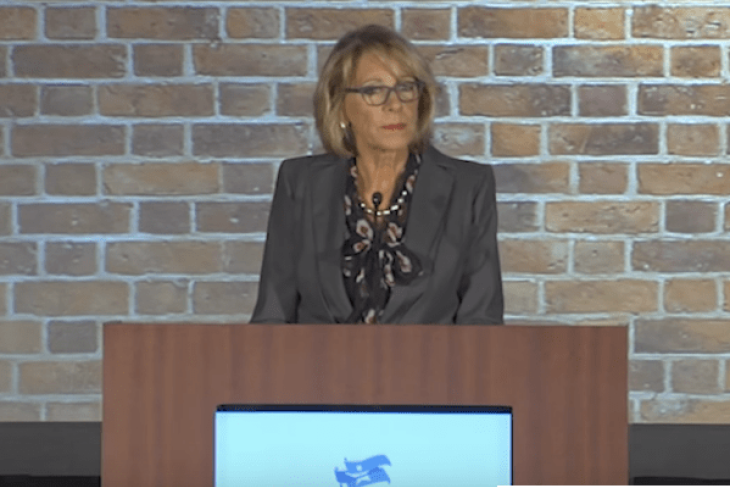

With the nomination of Betsy DeVos—the soon-to-be former chair of the American Federation for Children and a lifelong school-choice advocate—as the next secretary of education, many folks are now trying to understand for the very first time the role vouchers and private school choice play in the reform universe. Over the holiday weekend, several people approached me to ask where I stand on them as a matter of public policy and principle.

For clarity and context, a “voucher” is a way to pay for something, and in this case that something is private school. There are numerous devices that can achieve this goal (tax credits and education savings accounts, for instance), and some offer greater flexibility than others, but through the policy lens, they all accomplish the same thing: giving families and children who would not normally have the chance to choose private school the opportunity to do so. There are different flavors of private-school-choice advocacy, just like there are different flavors of charter-school advocacy, but they are broadly unified by this goal: more choices, more opportunities.

Private-school-choice supporters (among the bedrock of the reform universe writ large, as their advocacy typically crosses sectors and supports the work of those reforming school districts as well—support that is, incidentally, infrequently returned) have two general overriding philosophies. One is that competition and the marketplace, driven by parent choice, are the best ways to create, reward and regulate schools. They believe the government should not have a monopoly over the operation of schools with enrollment based on ZIP code. They also believe—and the research shows—that competition can drive improvement in public schools through the pressure generated by parental choice.

The second guiding belief is that there is something fundamental in the right to choose and in the ability of the right school to actualize human potential, in particular for low-income kids of color who grow up in places like Sandtown-Winchester. Which is to say, there is a moral imperative about the future of children who traditionally don’t have access to great schools that animates the support of the policy. These sorts of dichotomies are all the rage in education reform right now, but they are an older and long-standing dinner-table exchange among the private-school-choice set.

I am a fierce supporter of school choice—and that includes vouchers, tax credits, opportunity scholarships and all the other devices that make private schools part of the choice equation—and I am broadly on team two, believing we have a moral obligation to empower parents with more choices and greater freedom in how they choose to educate their child. My reasons are simple. Every local public school is not the right fit for every child, and no child should have to wait for a school to get better when there are other opportunities available regardless of governance. Nothing less than a child’s future is at stake every day they attend a school that is the wrong fit or that does not work simply because they did not win the parent lottery.

As we’ve heard since the DeVos announcement on Wednesday, some education pundits seem to believe that supporting vouchers is dooming the republic; that there is some larger good served by state-run school monopolies where low-income kids have the least leverage and the least opportunity. Though his support of charter schools has been laudable, one of these people, President Obama, currently sits in the White House. I’ve always found the president’s blind spot on private-school choice troubling given his own schooling, which included St. Francis of Assisi and the prestigious Punahou School in Honolulu, which he attended from grades five to twelve—on a scholarship. Though he is not the first political figure to ignore that his own life and success were profoundly affected by a private school, his lapse on this issue may be the most profound given his role as the country’s first black president. I’ve agreed with the president on a great many things, but in denying children the same opportunities we both had, we will disagree violently and always.

I imagine this discussion of private-school choice will only intensify as Betsy DeVos makes her full-blown transition to Secretary DeVos, working across states and in concert with Congress to create leverage for greater educational opportunity than exists today. From a technical perspective, this will prove difficult given the limited role the Department of Education is allowed to play within the framework of the Every Student Succeeds Act—a limiting supported by numerous Democrats in addition to Republicans. What the policy ultimately looks like may also be a creature of what is politically possible given the congressional agenda and the backlash in certain states against perceived meddling from the federal government. But those big caveats aside, it seems likely that “choice” in its broadest form will be a priority of both DeVos and the President-elect’s DOE.

But while lobbyists and editorialists bicker over the role vouchers and scholarships should play, I’ll be thinking of the kids in Sandtown, who need DeVos to use every bit of leverage she has, and to use it as quickly as possible.

When discussing the power of levers, Archimedes said, “Give me a place to stand, and I will move the earth.” I imagine that, for Secretary DeVos, that place will be the Department of Education and that lever will be school choice. And for far too many children, who have been relegated to the margins of our priorities for far too long, she can’t start pulling on it soon enough.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in a slightly different form in The 74.