This week’s Fordham-conferred grade of C on the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) will be worn as a badge of honor by some misguided souls in the science-education world, but it will be a disappointment to many. We know and regret that. Having carefully reviewed the standards, however, using substantially the same criteria as we previously applied to state science standards—criteria that focus primarily on the content, rigor, and clarity of K–12 expectations for this key subject—the considered judgment of our expert review team is that NGSS is not the cure the country needs for its abysmal performance in science.

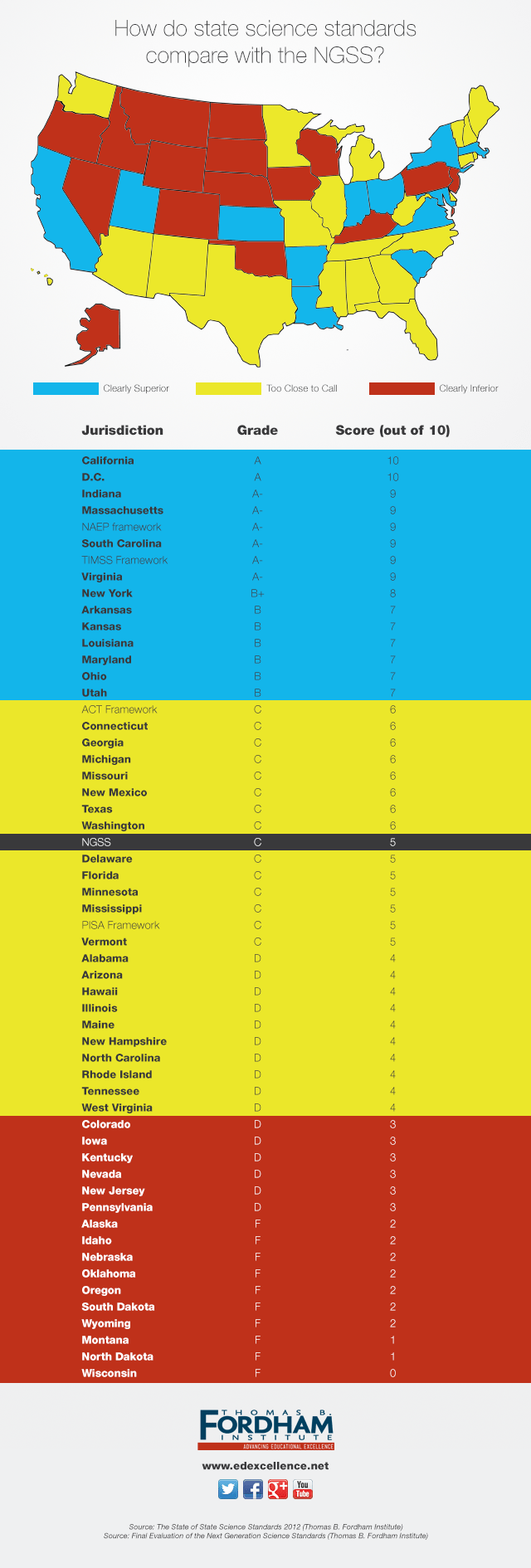

Yes, they’re better than the standards that many states are currently using—indeed, at least a little better than half the states and clearly superior to sixteen of them. On the other hand, five states (plus D.C.) earned grades of A or A- from our reviewers. So did the NAEP and TIMSS frameworks. Another seven states earned B’s. Check out the map and table below.

Yes, students and teachers in a bunch of states would be somewhat better off if their curriculum, instruction, and assessments were geared to NGSS rather than their abysmal present standards. But they’d be far better off if they Xeroxed (and faithfully implemented) South Carolina’s excellent science standards or if they constructed new ones around the commendable assessment frameworks of TIMSS and NAEP.

What’s the problem with NGSS? To be fair, it’s better in several important respects than its early drafts (on both of which our reviewers provided extensive feedback and recommendations for improvement.) It handles some topics and issues quite well, even elegantly, particularly in the earlier grades.

We recognize, too, that the drafters faced tough choices in pursuit of their goal of K–12 science standards that are “fewer, clearer, and higher.” The failure to make such choices can lead to “kitchen sink” standards that prove essentially impossible to implement. Our own understanding of good academic standards has benefited from the NGSS (and Common Core) efforts to set priorities, prune, and focus. Plaudits to NGSS and its authors (as well as the National Research Council that developed the framework on which NGSS is based) for facing up to the challenge of deciding what is most important for children to learn.

Still and all, the final NGSS suffer from five significant shortcomings.

1. Science standards should integrate and balance necessary content with critical “practices” through which students can extend learning and deepen understanding. The NGSS fail to achieve this balance; they too often gloss over or omit entirely the content that students need to make practices both feasible and worthwhile.

2. While ostensibly aimed at preparing all students to be “college and career ready,” the NGSS omit essential prerequisite content that would lay the groundwork for high school physics and chemistry, much less for college-level science. And the newly released “Appendix K,” which offers suggested “course sequences” for middle and high school, implies that the NGSS include the essential content that IS the foundation for high school physics and chemistry courses. They do not.*

3. Too often, the NGSS standards assume that students have mastered essential prerequisite content that was never actually spelled out in earlier grades. Good standards clarify and prioritize what content and skills are essential at each grade level—and build cumulatively so that expectations at every level have been adequately prepared for in earlier levels.

4. The NGSS incorporate “assessment boundaries” in some standards that are meant to limit the scope of knowledge and skills to be tested on state assessments, but will likely have the unintended effect of limiting curriculum and instruction, particularly for advanced students. What’s more, often the content that is excluded is grade appropriate and part of the necessary foundation for future learning.

5. NGSS fail to include much math content that is critical to science learning, especially at the high-school level, where it is essential to learning physics and chemistry. The Fordham reviewers note that the standards “seem to assiduously dodge the mathematical demands inherent in the subjects covered”— a missed opportunity as many states prepare to implement higher math standards under the Common Core.

Where do states go from here?

We at Fordham have long favored high-quality, multi-state, even “national” academic standards, so long as they originate with and are voluntary for states. We’re bullish, for example, about the Common Core English language arts and math standards because they are substantively strong and truly state owned.

There are definite advantages to “common” standards, including comparability, portability, and some economies of scale. Textbooks, for example, need not be customized to each state’s idiosyncratic standards and shared assessment instruments should be more economical than separate single-state procurements. The tests may be better, too—and yield results that can be compared across state lines, even internationally.

But “common” standards are not inherently superior to the work of individual states—and improved standards can come from multiple directions.

We advise state leaders seeking to improve their science standards to look to—and borrow from—other states that have developed clearer and more rigorous standards, as well as from sound national and international models and frameworks. We’re particularly positive about places like South Carolina and the District of Columbia, both of which are thorough as to content (without falling into the “kitchen sink” temptation) and serious as to rigor but also do a fine job of amalgamating well-thought-out practices with that content. Moreover, they’ve developed strong support materials that, if implemented well, will drive curriculum and assessment development and instruction.

One more key concern: Regardless of the quality of a state’s existing science standards, or the improvements the NGSS (or a different change) might bring, state leaders would be wise to consider whether they presently have the capacity to overhaul science expectations while they are still working to faithfully implement the Common Core standards for English language arts and math. If we’ve learned anything from the Common Core experience, it’s that implementation (including preparation of educators and the public) is vastly more challenging than adoption. It’s fruitless to adopt any new standards until and unless the education system can be serious about putting them into operation across a vast enterprise that stretches from curriculum and textbooks to assessment and accountability regimes, from teacher preparation to graduation expectations, and much more. Even the finest set of standards is but a hollow promise, absent thorough and effective implementation.

* The NGSS team says it will be releasing another appendix—there are already a dozen!—that will discuss college and career readiness. For now, we must assume that what’s actually in—and missing from—NGSS is intended to yield readiness for advanced study of science, including college-level science.