This is the fifth entry in Fordham’s education savings account Wonkathon. This year, Mike Petrilli challenged a number of prominent scholars, practitioners, and policy analysts to opine on ESAs. Click to read earlier entries from Michael Goldstein, Seth Rau, Matthew Ladner, and Jonathan Butcher.

When SB302 passed in Nevada, introducing the country to its first and only universal choice program, the laudatory blogs and editorials—followed by a few hedged headlines—started pouring in. Many celebrated a landmark moment for the choice movement, while others wondered about the long-term implications of this new frontier.

But as I read through each piece, I couldn’t help but think of the words penned a few months back by the CEO and founder of 50CAN, Marc Porter Magee, when reflecting on the advocacy process. He wrote: “There is nothing worse than ‘winning’ in your advocacy campaign only to find out that the policies you helped enact actually do little to address the underlying problem you are so passionate about solving.”

In full disclosure, while StudentsFirst is active in Nevada and helped Governor Sandoval and legislators enact several major school choice and accountability reforms this session, we specifically didn’t advocate on behalf of the ESA bill. These other reforms, including those that established a tax credit scholarship program, a new student-focused funding formula, and an Achievement School District to turn around the state’s lowest-performing schools, were higher priorities in our view.

We did argue that the expansive choice program established under SB302 should be designed to serve those students with the greatest needs; and that there needed to be meaningful efforts to ensure that the private schools, educational services, or materials accessed using ESA funds were serving those students well. But for the most part, our suggestions failed to make it into the final bill. So while we didn’t play an active role in seeing SB302 over the finish line, the reform community did. Chalk up the “win.”

Now we have to ask ourselves: Does SB302 address the problem we set out to solve?

That might be an impossible question to answer. But if we can take anything conclusive from the piles of research on education, it’s that no policy works in isolation. Whether ESAs (or any policy, really) turn out to be a catalyst for educational improvement in Nevada depends on a whole host of other contingencies, like whether there will be a sufficient supply of high-quality private schools or educational services, whether families have clear, accessible information about the options available to them, and whether the amount of ESA funds are sufficient for allowing all families to access the school program or educational service of their choosing. How ESAs work in conjunction with other reforms in Nevada to create a system of high-quality schools is also of paramount importance.

At the end of the day, the success of any educational reform is not about breaking new ground in “the movement,” but about the quality of the education students receive as a result of a change in policy. So what should Nevada pay mind to over the next few months if ESAs are to lead to improvements in the quality of education students receive across the state?

Demand—and how best to create it among all families. We know from the research on school choice that markets work best when families have full information about the educational choices available to them. We also know that access to information is often unequal. This can lead to a stratified system in which those with systemic know-how are able to engage, while those in the greatest need of options are least likely to know about them.

In Nevada, families with experience accessing services outside of the public education space are advantageously aware of the options available to them—and which ones work best for their children. Families without this experience, by contrast, often struggle to understand exactly what to demand from providers. If ESAs are going to work for all of Nevada’s families, the state must ensure that everyone is aware of the program and has a clear understanding of the quality of services on offer.

Nevada should work with other states with ESA programs to learn how best to drive demand toward high-quality options.

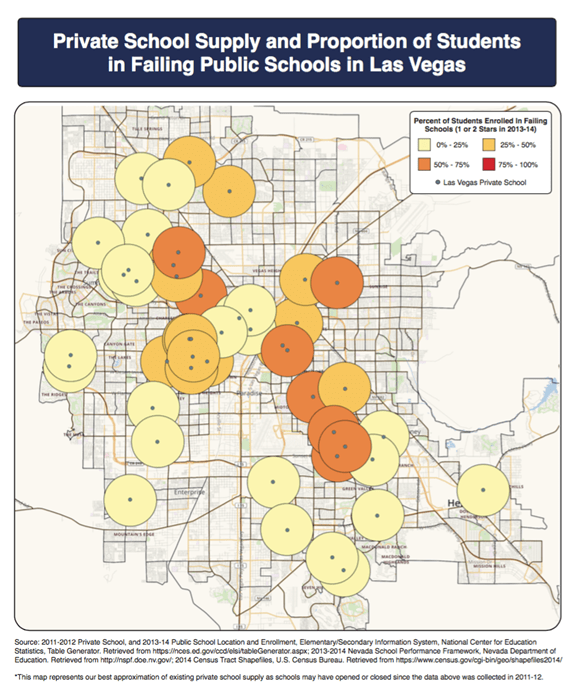

Supply—and the importance of managing quality. Private schools in Nevada—at least according to our back-of-the-envelope analysis—are plentiful, but more concentrated in affluent communities and areas where fewer students are in failing schools. The map below highlights the location of private schools across the most densely populated area of the state, Las Vegas. The circles are shaded based on the proportion of students in failing schools within a roughly twenty-minute walk of a private school.

We can see that private schools are far less likely to be concentrated in communities with large proportions of students in failing schools. We did this same analysis with the proportion of low-income families (both those at 185 percent and 300 percent of the federal poverty line), and it yielded the same result. No matter how you slice it, private providers are sparser in areas where kids really need more and better options. Equitable access to true school choice is an issue that Nevada will have to tackle if it wants to ensure the success of SB302 (and the opportunity scholarship bill passed this session as well).

Perhaps more importantly, the average cost of private school tuition in Nevada is between $8,000 and $10,000 dollars, well above the estimated $5,700 that low-income students can expect to receive through an education savings account. So at least in the short term, low-income families will have fewer options than affluent ones when it comes to spending their ESA dollars. Of course, it’s reasonable to assume that demand may drive supply over the long term; but as some have wisely pointed out, educators (and not charlatans) must drive this increase if ESAs are to be deemed a success.

And while the authors of SB302 should be commended for the level of transparency required in the law—information on student test results must be collected; disaggregated by grade level, gender, race, and family income level; and publicly reported—transparency alone is not enough. If ESAs are going to actually improve educational outcomes, state leaders must set a high bar for the quality of services offered by providers and use their authority to eliminate providers who consistently fail to meet the mark.

Systems—and how ESAs will work with other reforms to create a system of quality options. The state needs to remember that SB302 is only one of a handful of education reforms that were passed this session and will require their attention. In addition to SB302, Governor Sandoval signed a bill providing vouchers to low-income students, another that will dramatically alter the state’s funding formula by allocating resources to schools based on student need, and several more aimed at turning around struggling schools.

These bills seek to change pieces of the education system across the state, but many of them target the same students or are dependent on pieces of the other. ESAs for example, offer similar choices to families as the opportunity scholarship bill, raising additional concerns about supply. They also will be funded using the state per-pupil allotment, which is likely to increase for some students and decrease for others under the new weighted funding model. And all of these changes are taking place at the same time the state is working to improve the quality of its existing public schools through a newly-created Achievement School District and other reforms. If Nevada truly wants ESAs to improve the quality of education for students across the state, regulators must see to it that each policy works in concert with the others to create a system of worthy options for all students.

At StudentsFirst, we view private school choice as one of many levers that can help address the systemic inequities so many students face. I am not sure SB302 was ever designed to solve that problem, but if Nevada is thoughtful about the issues raised above, it has a decent shot of improving the education landscape in the state by raising the quality of education provided to its students.

Tracey Weinstein, Ph.D. is the director of policy and innovation at StudentsFirst, where she leads the organization’s policy research and legislative analysis unit.