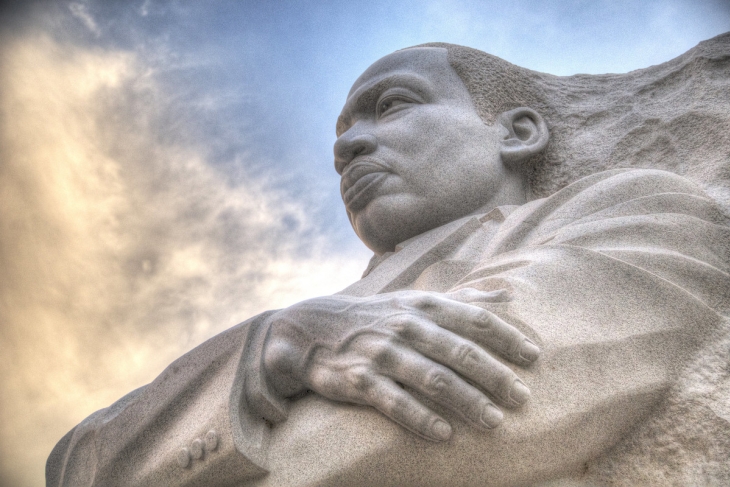

Last week, as we celebrated the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., we recalled his civil rights activism as an admirable example of creating what John Lewis called “good trouble.” Dr. King is an American icon precisely because he possessed the wisdom and courage to hold America up to her own high standards: that all men are created equal and must be treated equally before the law. Educators will teach their students about the activism of Dr. King, in the hope that students will be inspired to continue to work for the cause of justice. This practice is salutary. But we do not pause often enough to consider Dr. King’s own education and its connection to his activism.

We should not lose sight of the fact that Dr. King was liberally educated, and early in his studies—he entered Morehouse College as a freshman at the age of fifteen—he was convinced that a true education involved moral formation and a concern for the cultivation of interior freedom. It was at Morehouse that he was first introduced to the writings of Thoreau, whose essay “On Civil Disobedience” would become so influential in King’s own self-conception as an activist. It was also at Morehouse that King wrote a short piece in the school newspaper titled, “The Purpose of Education.” In that fiery article, he argued that education’s concern with intellectual virtue and critical thinking must be married to concern for moral virtue. “Intelligence plus character—that is the true goal of education,” he wrote. Even as a young man, King believed that knowledge and virtue must not he held apart. After all, he argues, “the most dangerous criminal may be the man gifted with reason, but with no morals.”

After Morehouse, King matriculated at Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, where he earned his bachelor of divinity in systematic theology through study of the classics of philosophy and the Christian tradition. At Crozer, he underwent serious study of the Western philosophical tradition, from Plato up to Hegel and Thoreau, which he writes about movingly in his autobiography. In his spare time, King was reading Marx solely to understand the appeal of communism. Although convinced that communism was “basically evil,” he wrote that it challenged him to see some problems in need of reform within the capitalist system, and how the profit motive could be an engine of inequality. It was also at Crozer that he was introduced to the writings of Mahatma Gandhi, whose philosophy of nonviolent resistance became central to King’s own political activism.

In his autobiography, he describes his “intellectual quest” for “a method” to help him to think about how to eliminate social evils like racism and poverty. It was in Gandhi that he found the method he was seeking. He writes, “The intellectual and moral satisfaction that I failed to gain from the utilitarianism of Bentham and Mill, the revolutionary methods of Marx and Lenin, the social contract theory of Hobbes, the ‘back to nature’ optimism of Rousseau, the superman philosophy of Nietzsche, I found in the nonviolent resistance philosophy of Gandhi.” His liberal study of the classical western canon led him to seek wisdom from South Asia.

Nor did King’s extensive study of philosophy cause him to lose his faith. If anything, it strengthened it, and led him to pursue a Ph.D. in theology. For the more he studied history, and the more he contemplated the twin evils of racism and poverty in America, the more King was inclined to believe in the reality of sin and man’s essential fallenness. He writes that “reason, devoid of the purifying power of faith, can never free itself from distortions and rationalizations.”

After Crozer, King pursued his Ph.D. at Boston University’s School of Theology, where he continued to study both philosophy and theology. That period of study solidified his two most important convictions: (1) the reality of a personal God and (2) the dignity and worth of all humans. What liberal education helped him to discover were the metaphysical underpinnings of these beliefs, and the arguments that he would need to defend them.

During his early years as a pastor, as King was deciding whether to support the Montgomery bus boycotts, he had to ask himself whether the means were in line with his moral principles. For he had studied his Machiavelli and Aquinas, and he believed with the latter against the former that good ends did not justify immoral means. Drawing on his study of Thoreau, he decided that the boycott was right and just because it was best understood as a refusal to cooperate with evil. Drawing on his study of Gandhi, he decided that nonviolent protest was the best means to express the power of Christian charity.

After the success of the Montgomery bus boycotts, King became an internationally recognized political figure. He returned to Morehouse College in 1962 to teach philosophy (see his syllabus and his final exam). It was a course in political philosophy, and if you study the syllabus carefully, you will see the sources of some of his most famous political statements, including his “I have a dream” speech and his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” In that letter, he calls on the figure of Socrates—a “nonviolent gadfly”—as someone who well understood that it is better to suffer injustice than to commit it. He also addresses the movement’s willingness to break the Jim Crow laws in Alabama. Drawing on St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, King notes that there is a distinction between a just law (one that accords with the moral law and eternal law of God) and an unjust law that merely expresses the will to dominate and subdue others. He also draws on the Protestant theologian Paul Tillich and the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber to argue that the laws of segregation are unjust. The letter is powerful—the work of a scholar-activist who genuinely wants to convince others of the righteousness of his cause and the legitimacy of his tactics.

Dr. King’s mastery of the Western canon deeply formed his intellect, which is the ultimate source of his activism. His liberal education helped him understand what justice is and how to fight for it within the limits of his deeply Christian commitments. As calls to “decolonize” the curriculum grow louder in today’s education circles, we should look to Dr. King as an eminent case for teaching the canon. The study of the classics helped Martin Luther King Jr. understand what is a good human being and a good citizen, and we should not forget, neglect, or downplay that aspect of his legacy for future generations.