Drafting state learning standards is a task simultaneously critical and thankless. In New York, where I opened an elementary school a few years ago, we are once again revising our standards.

This also means that interest groups are assaulting our regulators like rival politicians with a week to go before Election Day. A first grade parent who works for our state regulator told me that, between the drafting of ESSA compliance plans and the revised standards, few can tell which end is up. “Each group advocates for mom and apple pie,” she observed. Sure, poverty prevents kids from succeeding in many cases. “But educators are pragmatic,” she continued. “They want practices they can implement.”

One idea that works wonders is using texts of increasing complexity to push students’ critical thinking. New York’s proposed English language arts standards do not go far enough in underlining the central nature of text complexity to student progress.

An issue brief from Knowledge Matters sums up decades of research: “Preparing students to read college-level complex text is…a challenge for our whole school system. Only a rigorous K–12 education that teaches broad knowledge and skills, and thoughtfully includes a range of texts in every grade and every subject will get the job done.”

In two surveys the authors cite, taken ten years apart, 80 percent of respondents said their high schools expectations were set too low; and looking back, about 75 percent wished they had taken more challenging courses.

According to research cited in the issue brief: On average, as “the grade levels go up, growth in Lexile scores—a measure of text complexity—slows…Among students and texts, there’s very little growth in high school.”

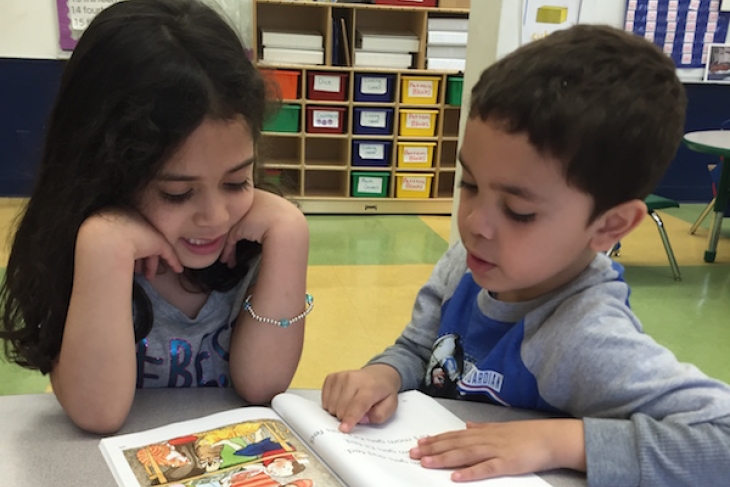

At schools like mine, there is no conflict. Whether the standards call for it or not, we always push our teachers and our students to tackle big ideas and complex understanding. As the Knowledge Matters paper points out, students’ reading levels track text complexity levels, suggesting that if given opportunities to work with more complex texts—they will succeed.

Every day I see the impact of this approach on my students. The conversations they have with their parents, the stories they write, and the art they create all reflect it. While these are very early data, the impact can also be seen in our assessment results.

But where leadership is uncertain, state standards send a critical signal. Regulators in New York would do well to spend some time with the research cited in this timely primer, and restore text complexity to its rightful place.

Matthew Levey is the executive director of the International Charter School of New York.