Considerable research suggests that “math skills better predict [individuals’] future earnings and other economic outcomes than other skills learned in high school,” report Eric A. Hanushek, Paul E. Peterson, and Ludger Woessmann. What’s true of people is also true of countries: “Growth in the economic productivity of a nation is driven more clearly by the math proficiency of its high school students than by their proficiency in other subjects,” they add. And no students are better poised to turn their mathematics education into economic advancement for the country as well as themselves than high-ability kids. They’re the young people who hold perhaps the greatest promise for making major advances in science, technology, medicine, and more.

Yet America’s high achievers have fared poorly for decades on international math tests, particularly in the upper grades, before they enter college and the workforce. The latest results of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), released late last year, suggest that—despite heroic efforts by school leaders, teachers, parents, policymakers, and reformers—nothing’s changed.

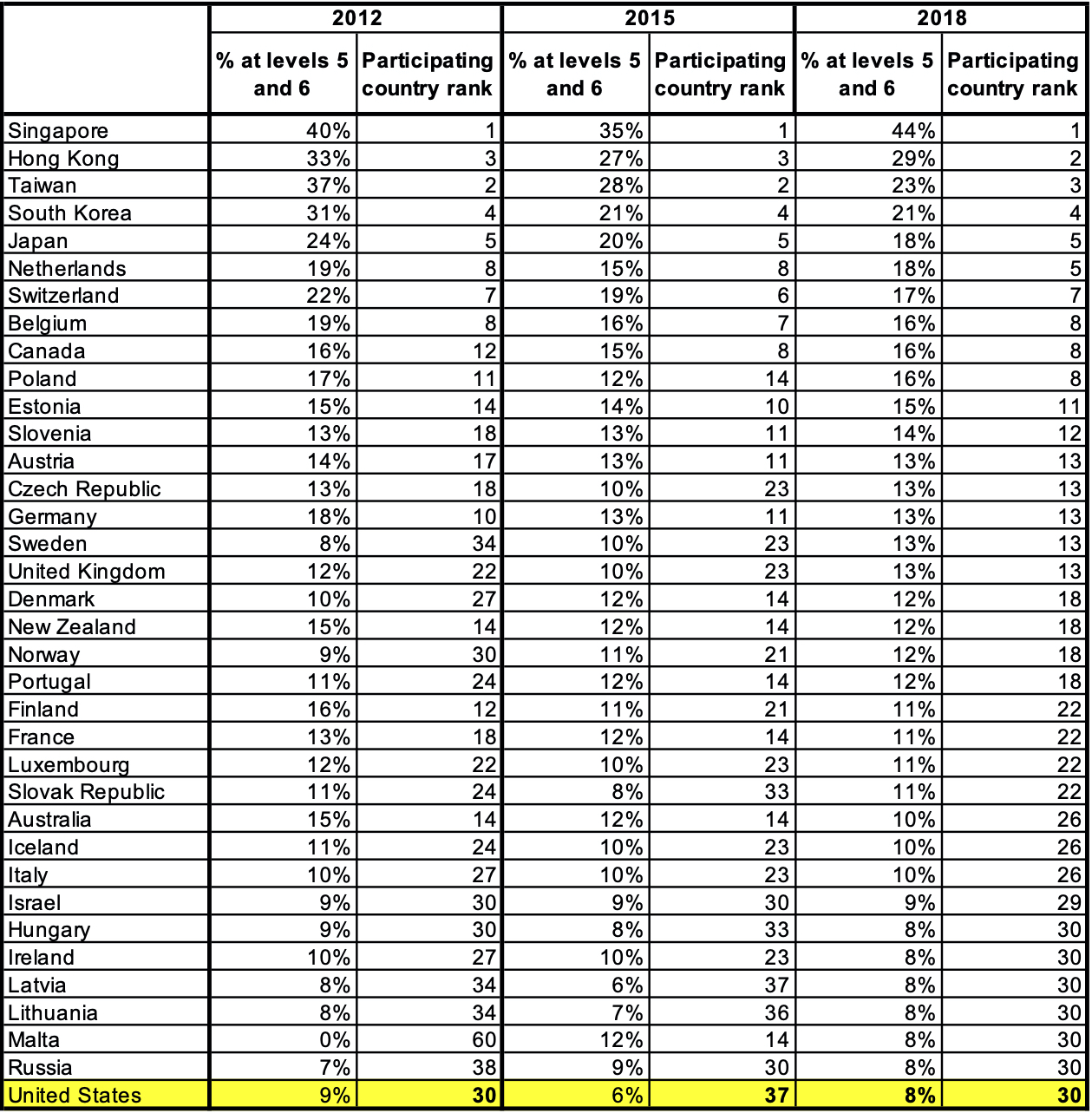

PISA assesses fifteen-year-olds and organizes its scores into seven levels from 0 to 6, with high scorers commonly defined as those reaching levels 5 and 6. Table 1 shows the percentage of test-takers who reached those levels in math over PISA’s last three iterations for the United States and every country whose results were the same or better than ours in 2018, as well as each country’s international rank in each of those years. (The list is ordered by countries’ performance on the 2018 round.)

Table 1: Percentage of high scorers on PISA math and rank among participating countries, 2012–2018, for countries matching or exceeding U.S. results

As is immediately clear, the United States has consistently fared worse than virtually all of our competitors, often by a wide margin. A whopping twenty-nine countries have a larger percentage of high achievers—including almost the whole of Europe and East Asia, Canada, and a smattering of countries elsewhere around the globe.

Moreover, despite some recovery from 2015’s somehow-even-grimmer results, our proportion of high achievers is a point lower than in 2012. And our rank is the same, placing us on the negative end of the year-to-year-progress spectrum: twenty of the thirty-five countries improved their rank; just eight fell, and all but one of them still outscore us. In fact, our percentage of students scoring at levels 5 and 6 hasn’t improved in almost two decades. Back in 2003, 2006, and 2009, our results were 10, 7, and 10 percent, respectively.

The problem is also deeper than these aggregate results are able to show. Five years ago, Checker Finn and I wrote a book about these very issues. Failing Our Brightest Kids: The Global Challenge of Educating High-Ability Students relied heavily on PISA math results, but also looked at TIMSS scores, which report on fourth- and eighth-graders, and dug into a number of socioeconomic indicators. Our conclusion then was more than alarming on both equity and excellence grounds:

Be it PISA or TIMSS…SES status, parent education, or the language spoken at home, America’s secondary students never do better than most of our competitors—not once. And we’re often at or near the bottom of the list, a deficit that deepens when we examine disadvantaged populations.

Yet here we are, a half decade later, evidently no better off.

Our book also examined reasons for this dismal situation, but those don’t appear to have changed, either. For starters, the United States has fared poorly at producing high achievers because we haven’t made this a priority. One-third of American schools don’t have any gifted programming at all, meaning they do nothing different or special for these kids during school, after school, or on the weekend. Among the two-thirds of schools that do something, many supply just small “enrichments” for an hour or two, better than nothing, of course, but unlikely to make much difference in students’ achievement. Among those that manage to offer more robust gifted programming, many staff it with teachers or non-teachers who have not been trained to educate bright students. And in the relative handful of schools that avoid the preceding pitfalls, many under-identify and under-serve low-income, black, Hispanic, and Native American children.

Yet the failure arises from more than simple oversight and neglect. Its roots include disputes over ideology, disagreement over the definition of “gifted” and how to identify children who meet that definition, squirrely data, feeble political support, fretting about “elitism,” and more.

Yes, there are a couple of bright spots. Given America’s large population, we have a greater total number of high achievers than many other individual countries—though, importantly, not the European Union as a whole, and perhaps not China. Recent fourth and eighth grade scores on the Nation’s Report Card also suggest that we’re doing something right for these kids, particularly in math, and maybe those results can be sustained in high school. But there’s little historical support for that. And we’re never going to truly turn around this big and persistent problem until we acknowledge it and set out purposefully and diligently to tackle it. That we should do for at least two big reasons. First, high achievers, especially those from disadvantaged circumstances, need and deserve our help. Second, better results are essential if America is to continue competing successfully in the global marketplace. As it stands, our place in the world is threatened by our educational shortcomings.