The Fordham Institute’s new report, Excellence Gaps by Race and Socioeconomic Status, authored by Meredith Coffey and Adam Tyner, is a significant addition to our growing knowledge about excellence gaps. Taken in concert with the recent report from the National Working Group on Advanced Education (of which I was a member), this work encouraged me to reflect back on over fifteen years of work on how excellence gaps form and how we can shrink and eliminate them.

The idea for the concept of “excellence gaps” first emerged while I was a fly on the wall at state-level education meetings and hearings in Indiana around 2006. Everyone was grumpy about NCLB and its implementation, but the conversations tended to focus on closing achievement gaps.

This got me wondering about two issues: Everyone was talking about “achievement gaps” as if there were just one gap; weren’t they really talking about “minimum competency gaps”? And would advocacy for advanced students be more effective if reoriented around the theme of achievement gaps? I began asking these questions of colleagues in Indiana and elsewhere, and eventually the concept of “excellence gaps”—those gaps at the top end of the achievement distribution—began to form.

Our first report on excellence gaps was released in 2010 to utter and complete silence. We couldn’t get traction with any academics, K–12 educators, or policymakers. Every major network promised to send a crew to our press conference at the National Press Club, but the only journalist who showed was from a D.C. weekly who never did a story on the report (some scars never heal!).

But things began to change. A colleague and I were walking through the hallways of the U.S. Department of Education when we noticed a program officer walk by with a copy of the report. A few weeks later, we learned that a state school chief was asking about the report. And we knew something was happening when a governor’s chief of staff called to express the governor’s displeasure “about how bad our state’s data look in your report.”

As the slow burn from the first report turned into real momentum, we produced a second report, a handful of additional papers, and even some initial thoughts on interventions. With the generous support of the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, we produced two detailed, state-level reports on academic excellence and excellence gaps.

The intervention work led to the Excellence Gap Intervention Model, which we recently validated and improved. The model has led to projects with districts across the country as they tackle excellence gaps. My team is especially excited about our afterschool interventions, which are part of the After School Excellence Network, but all the intervention projects are making progress.

I share this timeline to make a broader point: Even a decade ago, it was not surprising to have education leaders throw up their hands when faced with excellence gaps and say, “No one knows what to do! Let’s just get rid of advanced programs and at least we won’t have huge participation gaps on our hands.” This isn’t a terribly helpful attitude (it ignores both the symptoms and disease, so to speak), but I understood where it was coming from. Despite decades of related research, we just didn’t know enough.

Fast forward to today, and we do know enough. Indeed, we know far, far more than most K–12 leaders recognize. Advances in talent identification, curriculum design, differentiation, acceleration, and several other areas have been profound, and much of this research has resulted in strategies and interventions that educators can use immediately. The National Working Group on Advanced Education report does a great job of summarizing this progress, and I was honored to play a small part in the group’s work. There is simply no excuse for the old administrator attitude of “program elimination is my only option.” We know how to do this!

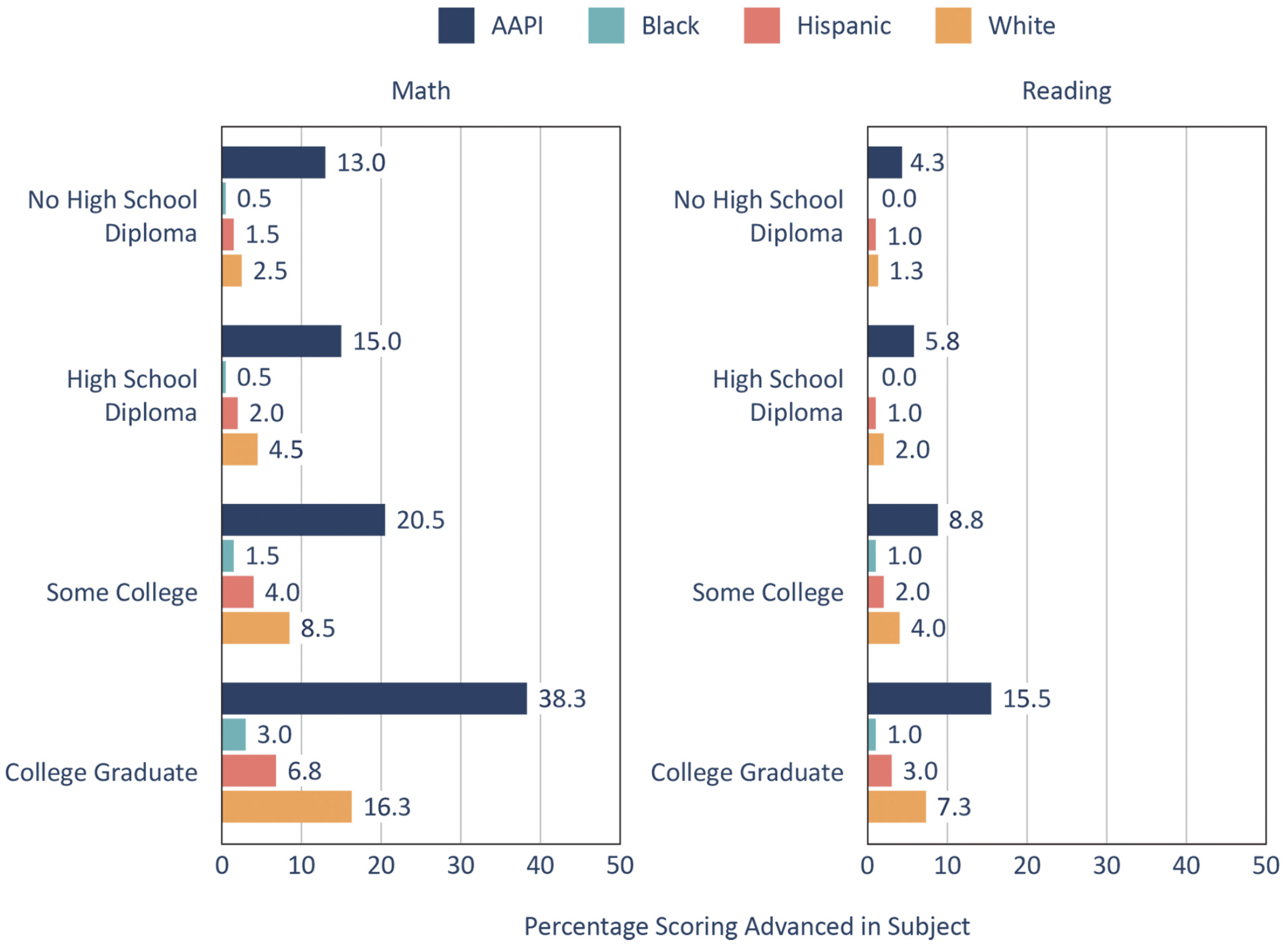

At the same time, foundational research on the nature of excellence gaps is still needed. In this regard, the report by Dr. Coffey and Dr. Tyner provides key insights. For example, excellence gaps by race or socioeconomic status have been frequently documented, yet this report also examined gaps by race and socioeconomic status. I have been playing with similar data for years and roughly knew what to expect, but seeing it depicted was still a bucket of ice water to the face (see, in particular, Figure 4 in the report, reproduced below). Among my takeaways is that racial excellence gaps get larger as one moves from lower to higher socioeconomic levels. Part of that is obvious: If there is little advanced achievement among students experiencing the lowest levels of economic security, then gaps will be relatively small. But that effect is confounded by the fact that, for Black and Hispanic students, the increase in advanced performance from low to high levels of socioeconomic status is very small; even at the highest levels, only 1 percent of Black students and 3 percent of Hispanic students score advanced. This causes me to wonder why the obvious benefits of higher economic security are correlated with higher advanced performance in some racial and ethnic groups but negligible in others. That finding alone is worth a national conversation.

Figure: Excellence gaps by race/ethnicity persist within student socioeconomic groups

Note from the report: “These are the [report] authors’ calculations from data representing eighth-grade achievement on the NAEP, averaged from 2015 to 2022. The measure of SES is the mother’s highest level of education. AAPI refers to Asian American and Pacific Islander students.”

Make no mistake, this will be a difficult conversation, not least because discussions involving race so easily descend into name-calling and accusations of bad faith. But as fraught as these conversations may be, we must have them.

Not to make anyone feel old, but we’re nearly a quarter of the way through this century. Since 2000, we have made amazing progress in our understanding of the nature of excellence gaps and how to address them. We can and should acknowledge this progress while noting the work yet to be done as we seek to develop the talents of all of our children. These two recent reports are important milestones and next steps on that journey, and I’m grateful to the Fordham team for their continued commitment to this work.