Editor’s note: This essay is an entry in Fordham’s 2022 Wonkathon, which asked contributors to address a fundamental and challenging question: “How can states remove policies barriers that are keeping educators from reinventing high schools?” Learn more.

The key to improving American high schools lies in allowing the field and families to lead the charge. Former New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg, for instance, allowed educators to create small high schools and closed underperforming ones. Bloomberg’s administration opened 656 new schools (142 of which were charter schools) and closed 96. MDRC, an educational and social policy nonprofit organization, conducted a random assignment evaluation of the small school program, finding:

Those findings show that the schools, which serve mostly disadvantaged students of color, continue to produce sustained positive effects, raising graduation rates by 9.5 percentage points. This increase translates to nearly 10 more graduates for every 100 entering ninth-grade students. These graduation gains can be attributed almost entirely to Regents diplomas attained, and the effects are seen in virtually every subgroup in these schools, including male and female students of color, students with below grade level eighth-grade proficiency in math and reading, and low-income students.

In addition, the best evidence that currently exists suggests that these small high schools may increase graduation rates for two new subgroups for which findings were not previously available: special education students and English language learners. Finally, more students are graduating ready for college: the schools raise by 6.8 percentage points the proportion of students scoring 75 or more on the English Regents exam, a critical measure of college readiness used by the City University of New York.

New York City’s small school initiative succeeded, but sadly the short attention spans of philanthropists and policymakers got distracted. The success of smaller schools, however, is not limited to the New York program, or to high school. Arizona saw a net increase of 1,221 public schools in the year before the advent of charter schools in 1995 and the 2020–21 school year. The average public school size fell from 649 to 471 during this period, and the state also adopted policies to allow students to attend private schools (which tend to be smaller).

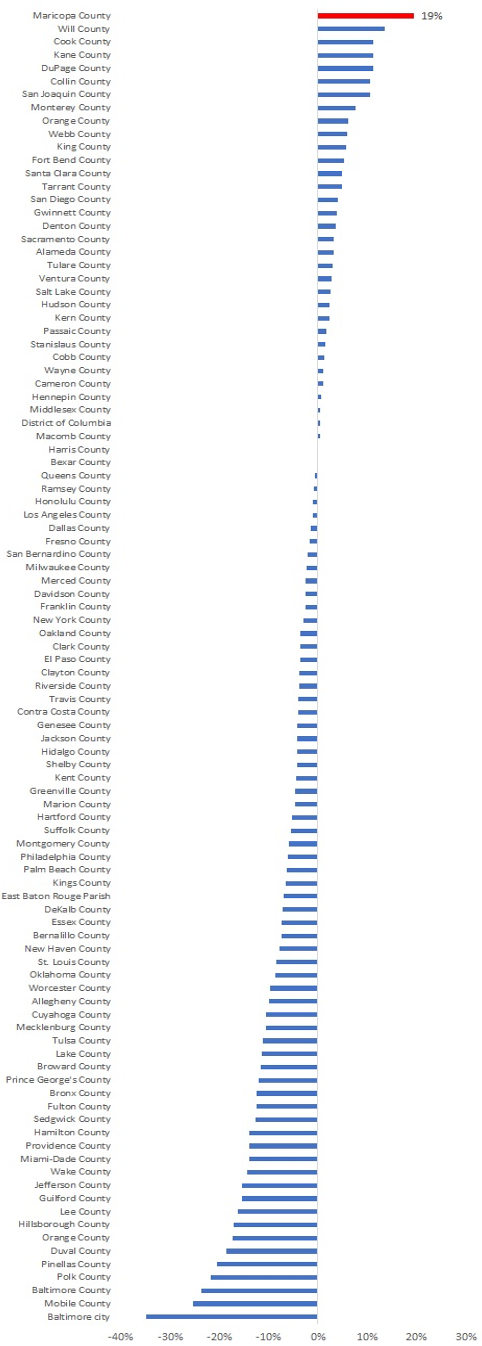

Disentangling competitive effects from small school impacts lies beyond the limited powers of your humble author, but something went right. When the Stanford Educational Opportunity Project, however, linked student testing data from across the country for grades 3–8, the results looked very favorable for Arizona. Arizona had the highest statewide rate of academic growth for poor students, and Maricopa County had the highest rate of academic growth for poor students among the top 100 counties nationwide (see Figure 1).

Just to be clear, this means that Arizona students learned faster than students elsewhere, not that they had the highest test scores. As a state with a majority-minority student population and the holder to the short end of a number of achievement gap sticks, a faster rate of academic growth is needed to close gaps. If I wanted to be cruel, I would dig up spending per pupil in Maricopa County to that in Baltimore, but that would constitute bad sportsmanship.

Figure 1. Academic growth rate for economically disadvantaged students in the 100 largest American counties, 2008–18

Source: Stanford Educational Opportunity Project.

American families have been moving on the small-school agenda faster than policymakers. Years before the outbreak of Covid-19, homeschool co-ops began to take hold, including in places like Silicon Valley. In early 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic hit America, and a Facebook group called “Pandemic Pods” created a remarkable example of spontaneous order.

A study by Tyton Partners found that more than 15 percent of families switched their children’s school for the 2020–21 academic year. Charter schools, homeschooling, learning pods, and microschools all realized net increases. The net impact of all of these trends was towards smaller learning communities. The pandemic catalyzed the growth of supplemental learning pods (a cohort of students gathering in a small group with adult supervision and outside the framework of their traditional physical or virtual classrooms) to learn, explore, and socialize.

Many of these parents went back to district schools when lockdowns ended, but others did not. All will carry with them the memory of their time in the education wild. While many deeply disliked impromptu Zoom schooling, others made some version of it work. Polls indicate large and as of yet unfilled yearning on the part of parents for a more flexible K–12 system.

A demand-driven system will embrace and replicate schools that work and discard those that fail to produce. A top-down political system has (predictably) failed to perform this task. Families pursuing the interests of their children will succeed in driving progress. Expanding the opportunities for them to pursue happiness in small, tight-knit communities represents an appealing and productive future.

Finally, American families have ways to shrink public school enrollment besides creating small schools. They unfortunately implemented one of those in 2007 with the advent of a Baby Bust, the leading edge of which has entered the high school grades. The National Center for Education Statistics projects declines in public school enrollment in all but a small number of states. Like it or not, the status quo is not an option, but a more vibrant and pluralistic education system can be co-created by educators and families.