Editor's note: This was first published on the author's Substack, The Education Daly.

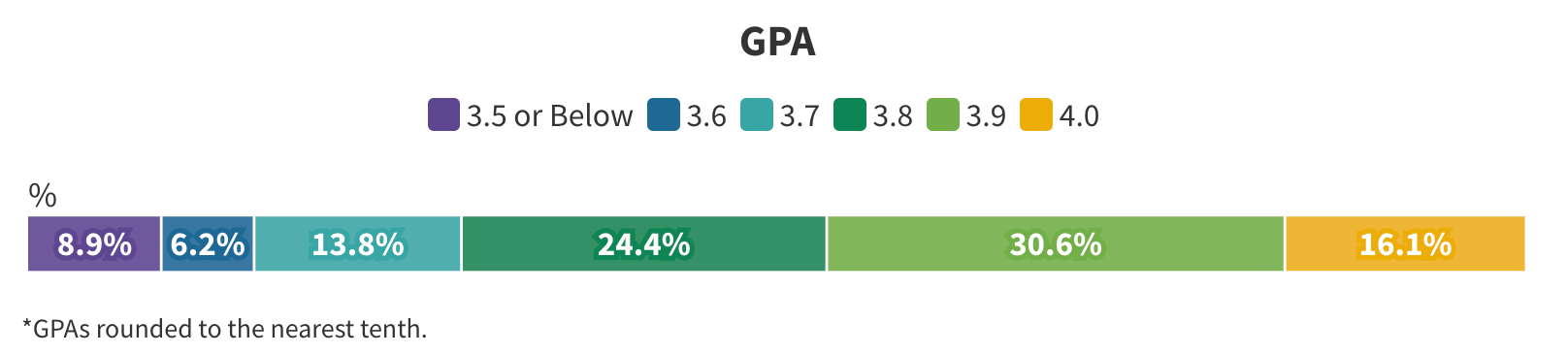

You would be hard pressed to find a better encapsulation of grade inflation than the graph below. It comes from the Harvard student newspaper’s survey of 2022 graduates. The purple band on the far left, which includes just under 9 percent of Harvard’s most struggling students, is for those with grade point averages of 3.5 or below. Everyone else—91 percent of the senior class—reported earning a 3.6 or higher.

It looks bonkers. How can all of Harvard’s students possibly be earning such high grades? Do we even need six different categories in this graph? Aren’t we just distinguishing the kids with all A’s from their peers who scraped along with almost all A’s?

Many people find this extremely frustrating. To them, privileged Ivy League kids are being handed grades they could not possibly be earning, which will in turn guarantee them admission to the best graduate schools and job offers from the most prestigious companies. Harvard sucks! Go ahead, say it and get it out of your system so we can move on.

This narrative about college grade inflation goes back decades—at least to the 1960s. The trends are impossible to deny. Grades rose much faster than achievement—particularly at private institutions. Professors became more willing to hand out A’s and less likely to give C’s or anything lower. It has been widely reported in the press, researched in depth, and addressed by blue-ribbon committees. I won’t bore you with the details. Bottom line: None of it made any difference. Grade inflation marched onward and upward.

That problem is not my focus in this post.

For me, grade inflation isn’t important as it relates to Harvard students but as it relates to low-income students in our K–12 schools. When they receive inflated grades, it’s not a windfall of unearned currency that opens doors to future success. Instead, grade inflation often robs them and their families of critical opportunities by giving them falsely reassuring messages. It’s not a victimless crime. In fact, it’s one of the most important—and under-discussed—issues in education today.

In part 1, I lay out the basic shape of the problem. In part 2, I will consider possible fixes.

What is grade inflation?

We need a definition. Grade inflation is the tendency to award increasingly positive marks to students without any corollary improvement in the quality of work or student performance.

It often makes grade descriptors sound ridiculous. For instance, some school systems define a B grade as “above average.” But if 90 percent of students are earning a B or better, that’s weird because 90 percent of students can’t be above average. Garrison Keillor used to joke about this. Grade inflation.

Is grade inflation actually a problem?

Not everyone thinks so.

For almost as long as curmudgeons have been lamenting grade inflation and ordering pampered younger generations to get off their academic lawn, there have also been rebuttals from those who feel it’s not a real crisis. They have some good points that are worth considering. Here are a few:

Higher grades increase kids’ confidence and encourage them to persist. There’s a really interesting paper by two professors, Zachary Bleemer and Aashish Mehta, who considered what happens when a college only allows students to major in a rigorous subject—economics—if they earn a 2.8 GPA in their introductory economics courses. Quite a reasonable policy, right? The students who fall short of the 2.8 generally choose a less rigorous major...and end up earning substantially less income in their careers. But the researchers found that those students who were prevented from sticking with economics generally would have succeeded if they were allowed to continue—and they would have gotten higher-paying jobs. A bit of grade inflation to get them over the 2.8 GPA bar would have been a productive thing, they argue.

How persuasive is this argument? It’s provocative. It’s also a stronger case against having a minimum GPA requirement for economics than a case for grade inflation, but if we’re trying to diversify the pool of kids who earn economics degrees, we shouldn’t be pushing out kids who could succeed. Fair enough.

Even when inflated, grades make it possible to distinguish the strongest students from peers. According to this perspective, grading scales are arbitrary. There is no shared definition of an A. No matter which system is used, the top performers get the highest marks and the lowest performers get the worst. Schools can rank students or bestow honors and awards on those who have earned them. Going back to our Harvard example above, the 4.0s stand apart from the 3.7s. As long as there remains a discernible hierarchy, grade inflation isn’t a real issue.

How persuasive is this argument? If we are using grades to compare students across an entire grade or school, this argument makes sense. But it sees the world through the eyes of an administrator. What about parents? They have no clue what grades the other students are earning. They rely on grades to tell them whether their kids are thriving academically. If they earn A’s, they assume those A’s mean the same thing they did back when the parent was in school. In these cases, inflation leads to distorted messages. We will come back to this issue. It’s a key part of the whole picture.

There’s new evidence about grade inflation for us to consider

More lenient grading seems to contribute to absenteeism. Wait, really? Yes. Researchers recently found that when North Carolina changed its policies for high school students so it became easier to earn good grades, struggling students began missing more school—while there was no similar increase in absenteeism for high performers. Grade inflation widened performance and attendance gaps. Given that we are trying to reverse a national epidemic of chronic absenteeism, we should be particularly worried by these findings. They show that not all students have the same response to lenient grading. Thriving students gobble up the better grades like Pac Man pellets when it is easier to get them. Other kids are content to earn the same mediocre grades while investing less effort.

Grade inflation got worse during the pandemic. My organization, EdNavigator, today joined TNTP and Learning Heroes in publishing new data on this trend. In False Signals: How Pandemic-Era Grades Mislead Families and Threaten Student Learning, we looked closely at patterns in two diverse districts from 2018–22 and observed the following:

- Student achievement fell significantly. The average student is five months further behind in math and English language arts than was the case before the pandemic.

- Chronic absenteeism went through the roof. About one in five students is missing at least 10 percent of school days—or eighteen days per year. This figure has more than doubled in both districts compared to 2018.

- Yet most students are still earning the same grades—or even better grades.

- That’s a really concerning trifecta: lower performance, worse attendance...and grades that didn’t change. As of 2021–22, about 40 percent of the students in these two districts who were chronically absent and not performing on grade level according to state tests nonetheless earned grades of B or better.

- No wonder American parents are convinced that their kids have already recovered from any pandemic-era setbacks.

- If report cards have contained nothing but happy news, why would parents have any reason to believe there had ever been any setbacks? Why would they register their kids for supplemental tutoring? Or voluntarily send them to summer school? They wouldn’t—and this is a big reason why our pandemic recovery is not going very well. In many states, students—particularly those from less privileged homes—are still lagging behind their 2019 performance levels.

- These patterns of pandemic grade inflation were widespread. Also released today, Dan Goldhaber and Maia Goodman Young reviewed nearly a decade of middle and high school grading data for math, science, and English courses in Washington State. In their paper, they find that after state officials directed district leaders beginning in March 2020 to ease grading standards, GPAs in all three subjects rose sharply—and did not return to pre-pandemic levels even during the 2021–22 school year.

- Importantly, Goldhaber and Goodman Young show that the connection between grades and student performance on state tests—particularly in math—weakened. Inflated grades became a fuzzier achievement message for parents. In this case, we’re talking about an entire state rather than the two districts we featured in False Signals.

- Alyssa Rosenberg has a very nice column summarizing the studies and implications in the Washington Post.

But wait… there’s more! Tom Swiderski and Sarah Crittenden Fuller also recently published a paper on North Carolina that echoes, almost word for word, the findings in Washington State. They suggest that the “growing gap between student GPAs and achievement could be contributing to parents’ confusion about the extent of their children’s needs for pandemic recovery supports and an under-utilization of recovery programs.”

Truly an avalanche of research.

Although these policies reflect genuine empathy for students and families during a difficult time, we are seeing a rapid accumulation of reasons to believe that grade inflation is harming the very students it was intended to help.

—

In part 2, we will look at options for addressing all this grade inflation with an emphasis on practicality. Principals firing off memos ordering their teachers to grade harder is not going to work here.

Fortunately, some smart folks from a wide array of perspectives have thought about this problem. We will see what we can learn from them. I’ll add my own recommendations.