A simple observation: In the U.S., high school graduation rates have increased while other measures of academic achievement—from college entrance exam scores to high school NAEP scores to college enrollment—have stagnated at best. Taking this observation as the foundation, a new working paper from researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Texas at San Antonio argues that this pattern suggests “a decline in academic standards,” and then builds on that foundation to examine the consequences of changes to grading standards upon student behavior, academic effort, and learning.

The paper begins by investigating the theoretical connection between academic standards and student effort using mathematical models. Theirs is not the first attempt to do this. Going back to the 1980s, economists have shown through such formal models that, when academic standards change, students are likely to react. For example, rising standards may make some students expend greater effort to meet the new standard while inducing some lower-performing students to just give up. The present paper develops a model suited to the more nuanced effects of grading policies, and its authors’ model shows that, in theory, lenient grading could have either positive or negative effects on student effort. After all, while a lower bar may put an academic goal, such as passing a course, within reach of students who expend a bit more effort to reach it, other students may decide to take it easy when they are graded more leniently.

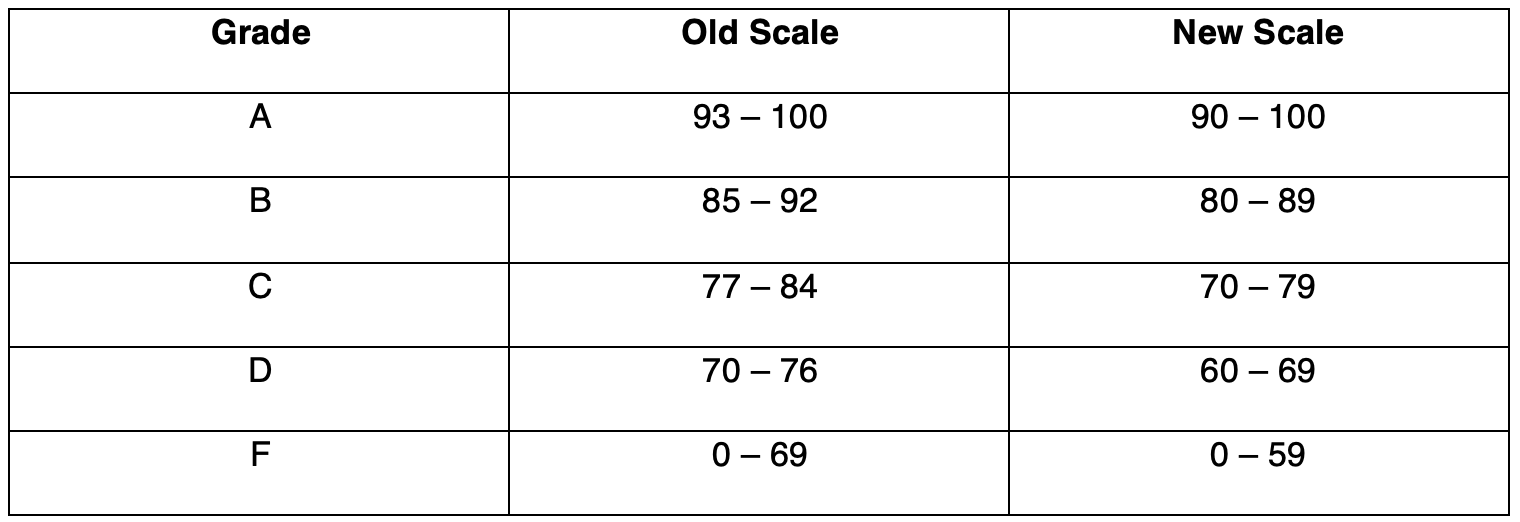

To test their model’s predictions, the researchers use grades, end-of-course test scores, ACT scores, and graduation data from North Carolina and leverage the fact that the state implemented a one-time change to grading policy that led to a drop in standards. In 2016, the state of North Carolina implemented a statewide change to the correspondence between number grades (0 to 100) and letter grades (A to F), and the result was more lenient grading (Table 1). For example, the minimum grade needed for an A dropped from 93 to 90, while the minimum passing grade (a D) dropped from 70 to 60. To identify the effects of this more lenient grading policy, they compare the outcomes of ninth grade students in the last cohort with the old grading policy to those of their counterparts in the first year of the new, more lenient policy.

Table 1: Grading scale changes in North Carolina

Note: Adapted from A. Brooks Bowden et al., 2023.

What their analysis finds is troubling. First, more lenient grading led to an average GPA increase of 0.27 points, while scores on North Carolina’s end-of-course exams stayed flat. In other words, the policy led to instant grade inflation. Even more troublingly, it also led to measurable declines in student attendance. That means that the more lenient grading policy not only inflated grades, but it also helped cultivate the culture of chronic absenteeism that later accelerated during the Covid-19 pandemic.

It gets worse. The grade inflation accrued only to students who were already higher achieving, while it was lower-performing students who missed class more. You can see where this is going: Higher-achieving students are fine; they are self-motivated, or they have pressures from family and peers that keep them going. Lower-achieving kids, for whom school more often provides the only source of accountability for their academic work, show up less and learn less. Academic leniency is promoted by people who think they’re doing disadvantaged students a favor. As it turns out, lenient grading in North Carolina did those students no favors at all.

The harm to lower-performing students does not end after the first year. The researchers find that academic disengagement (measured by absences) persisted as these students continued through high school, while achievement gaps (measured by later ACT scores) eventually widened. Although the effect was small and not statistically significant, there was suggestive evidence that lower-ability students were slightly more likely to graduate high school after the reduction in standards, which of course previews the enduring observation with which we started, a pattern that’s even more of a problem in the post-pandemic era: As chronic absenteeism reaches an all-time high, graduation rates keep going up. Keeping young people off the streets and in school is a worthy goal, and lowering certain standards might be justified in some cases if it leads many students to stay in school and learn more. In the North Carolina case examined in this paper, however, it seems hard to justify the lower attendance, decreased effort, and larger test-score gaps based on the statistically insignificant—yet slightly positive—effects on high school graduation.

This is far from the only research showing that soft grading standards reduce student learning. Studies from Florida to Norway, as well as a 2020 Fordham report that also used data from North Carolina, all show that students tend to learn less when assigned to teachers with lower grading standards. At a time when academic achievement has plummeted, this is yet another reason we ought to beware of the new wave of policies that lower standards and expectations further, such as “no zero” policies and prohibitions on penalizing student grades for turning in work late or even for cheating.

In the moment, lowering standards seems like an act of charity, giving grace to a struggling, needy student. What this research helps show is that, in the longer run, falling standards mean lowered expectations and diminished learning. The researchers of the present study put it this way: “The short-run gains of artificially raising high school completion rates may result in a permanent widening of long-run” disparities.

SOURCE: A. Brooks Bowden, Viviana Rodriguez, and Zach Weingarten. “The Unintended Consequences of Academic Leniency,” retrieved from Annenberg Institute at Brown University (2023).