Editor’s note: This is an edition of “Advance,” a newsletter from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute written by Brandon Wright, our Editorial Director, and published every other week. Its purpose is to monitor the progress of gifted education in America, including legal and legislative developments, policy and leadership changes, emerging research, grassroots efforts, and more. You can subscribe on the Fordham Institute website and the newsletter’s Substack.

This week, the U.S. Department of Education released results for the 2022 Nation’s Report Card—the most extensive assessment yet of how American students fared during the pandemic, and what my colleague Checker Finn has fittingly called “the little-known test that matters the most.” Building on other NAEP data for nine-year-olds released earlier this year, this latest batch gives us new reading and math scores for fourth and eighth graders across the country, as well as for each state and twenty-six large urban school districts.

The results are dismal, with significant drops nationwide and in almost every state and school system—and in both subjects and both grade levels. Math scores saw the steepest declines, no doubt because learning math depends more on classroom instruction than reading, which students learn and practice outside of school, too.

This is terrible news for our young people and our country, as many analysts have already explained in all sorts of outlets this week. The losses will take years and years to recover, if they ever do. This newsletter, however, focuses on advanced education—that is, how we’re doing as a country with kids who reach the high end of the achievement spectrum. In that regard, NAEP yields two kinds of informative results: the percentage of test-takers who reach its “Advanced” level, as set by the test’s governing board, and the composite scale score for those who reach the 90th percentile.

Looking closely at those metrics, the new data look a bit different for high achievers than for American K–12 students in general.

That doesn’t mean the news is good, but at the high end of the spectrum, in most places, it’s not particularly bad. In fourth grade math, and in fourth and eighth grade reading, scores remained flat or dropped to levels they were hovering around before Covid struck. These plateaus and smaller drops are—to be sure—bad things, but after years of pandemic-caused partial schooling, they seem both better than one would expect and remediable.

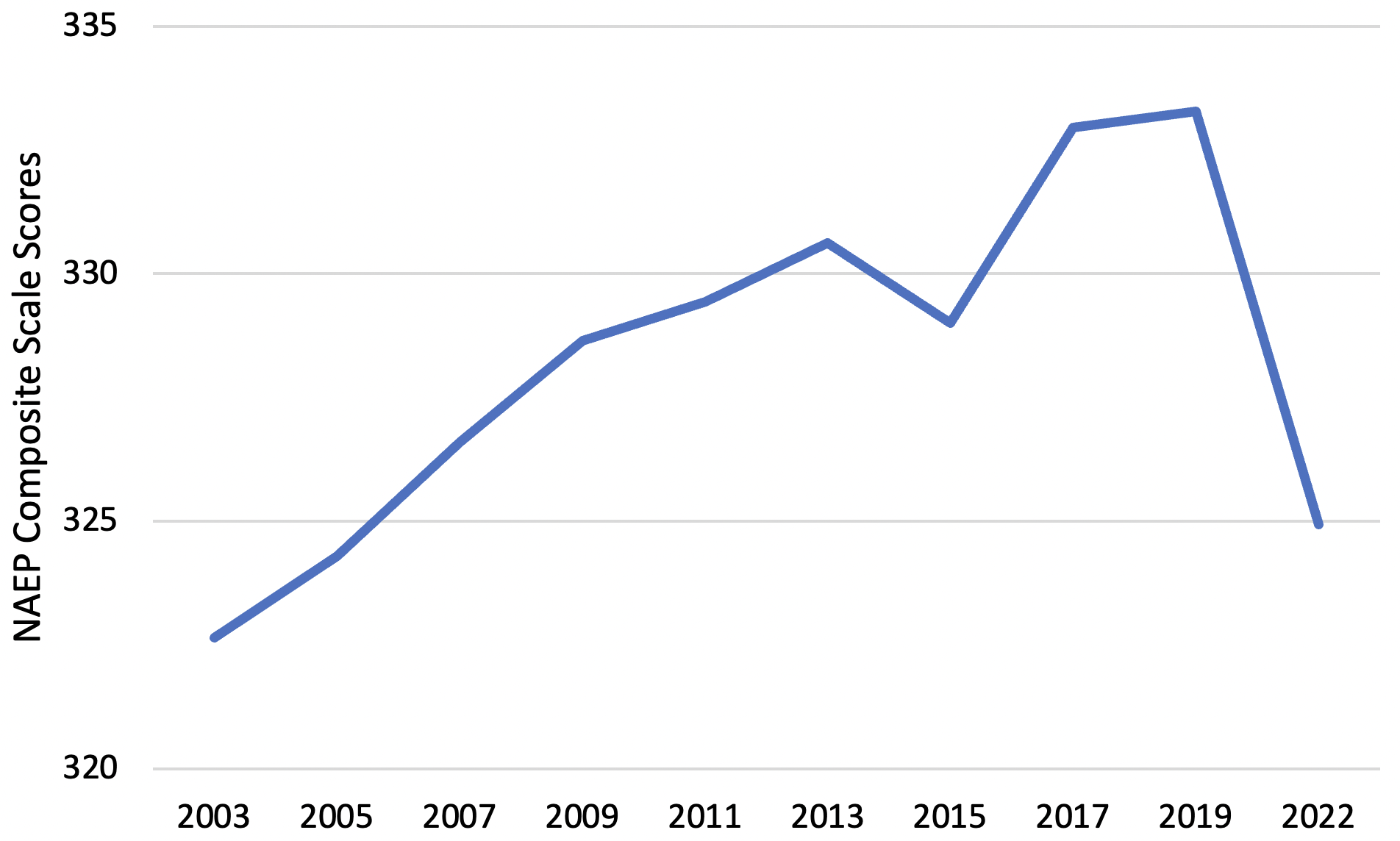

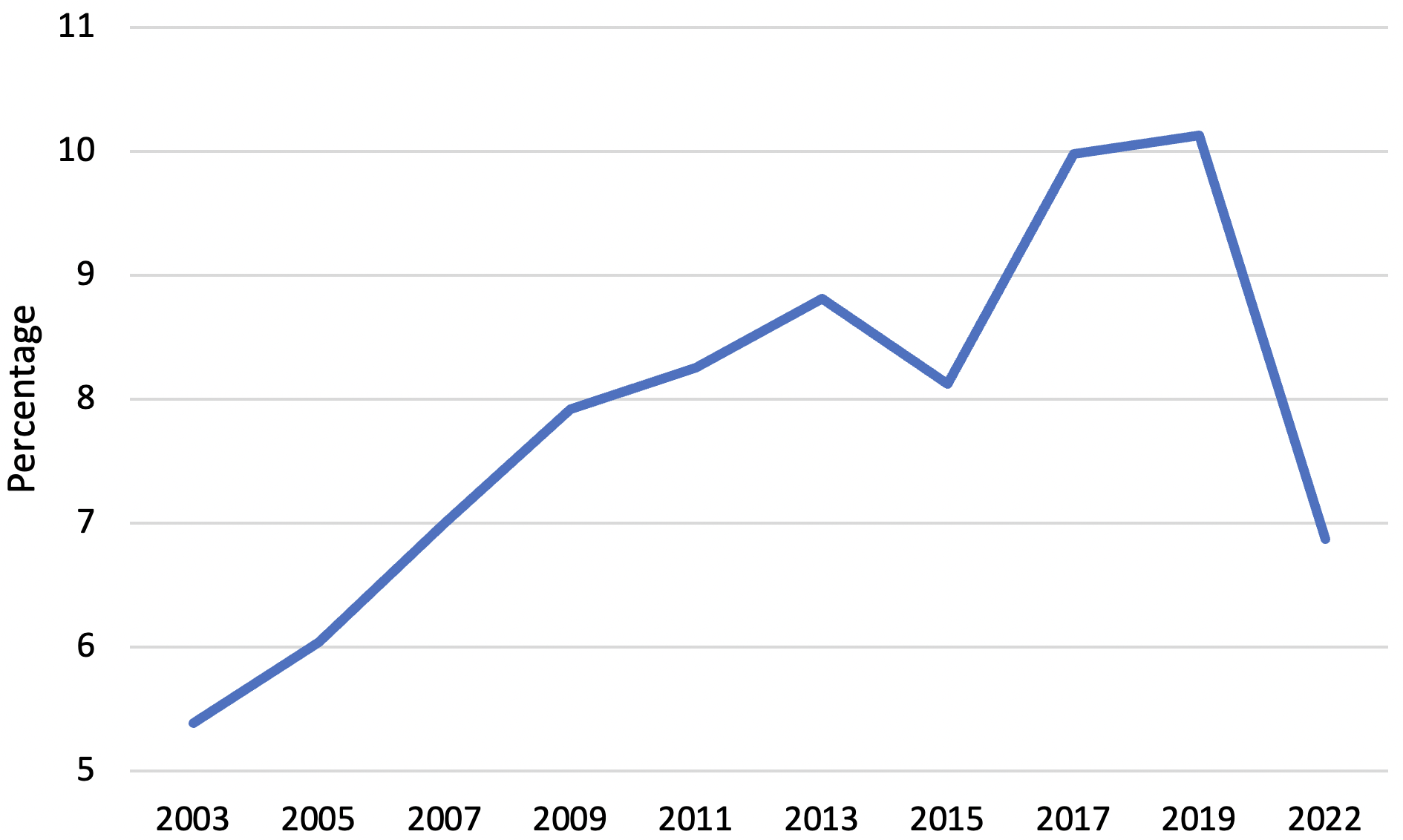

Eighth grade math, however, looks like the aftermath of Hurricane Ian. Almost two decades of progress have been lost. The 90th percentile plummeted to a score not seen since 2005, and the percentage of test-takers at NAEP “Advanced” fell to its 2007 level. (See figures 1 and 2.)

Figure 1. NAEP 90th percentile composite scale score, eighth grade math, 2003–22

Figure 2. Percentage of test-takers at NAEP’s “Advanced” level, eighth grade math, 2003–22

The figures speak for themselves, but note how progress, barring a small drop in 2015, has been swift and consistent for decades—and how pandemic-related school closures and other challenges wiped almost all of that away in one fell swoop.

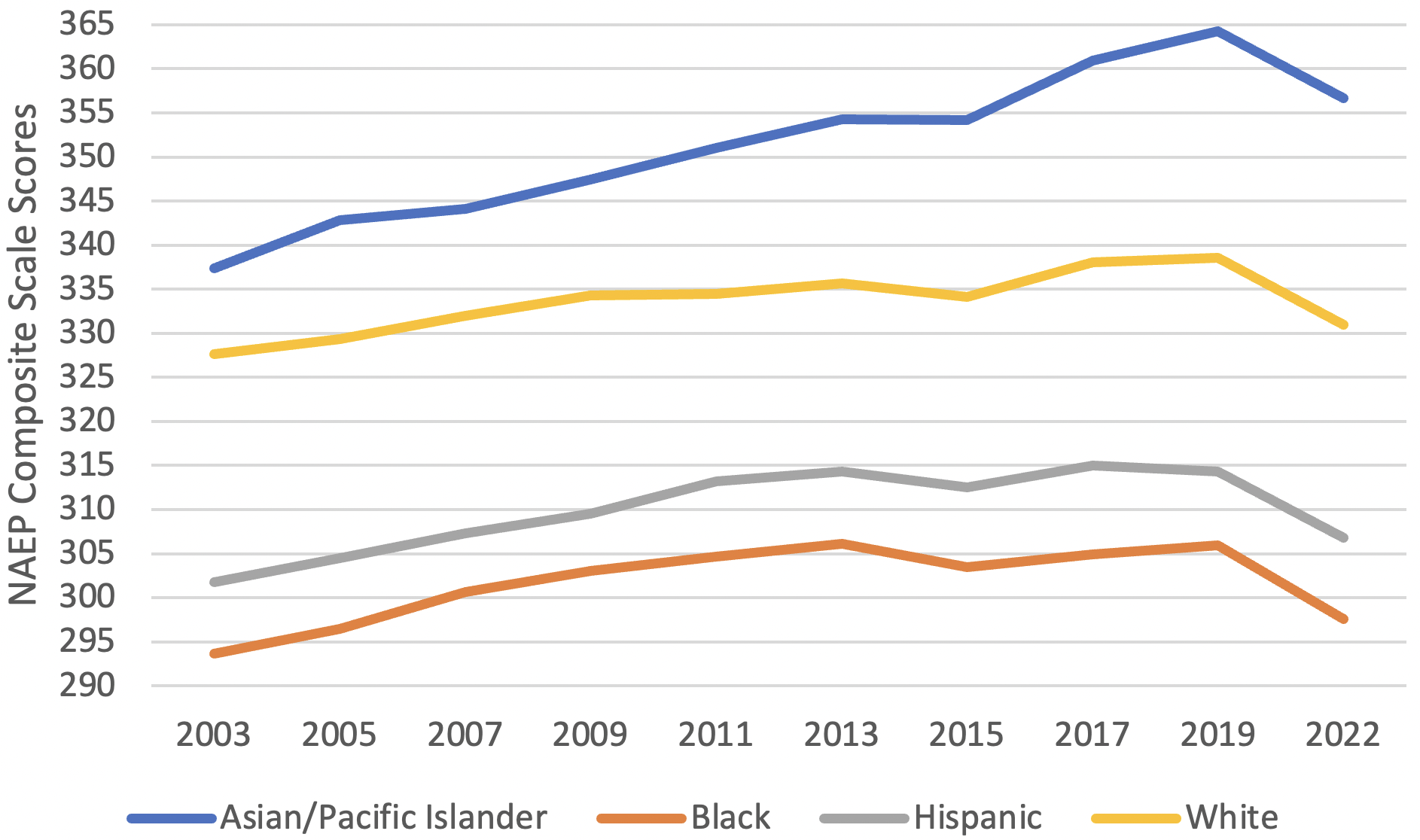

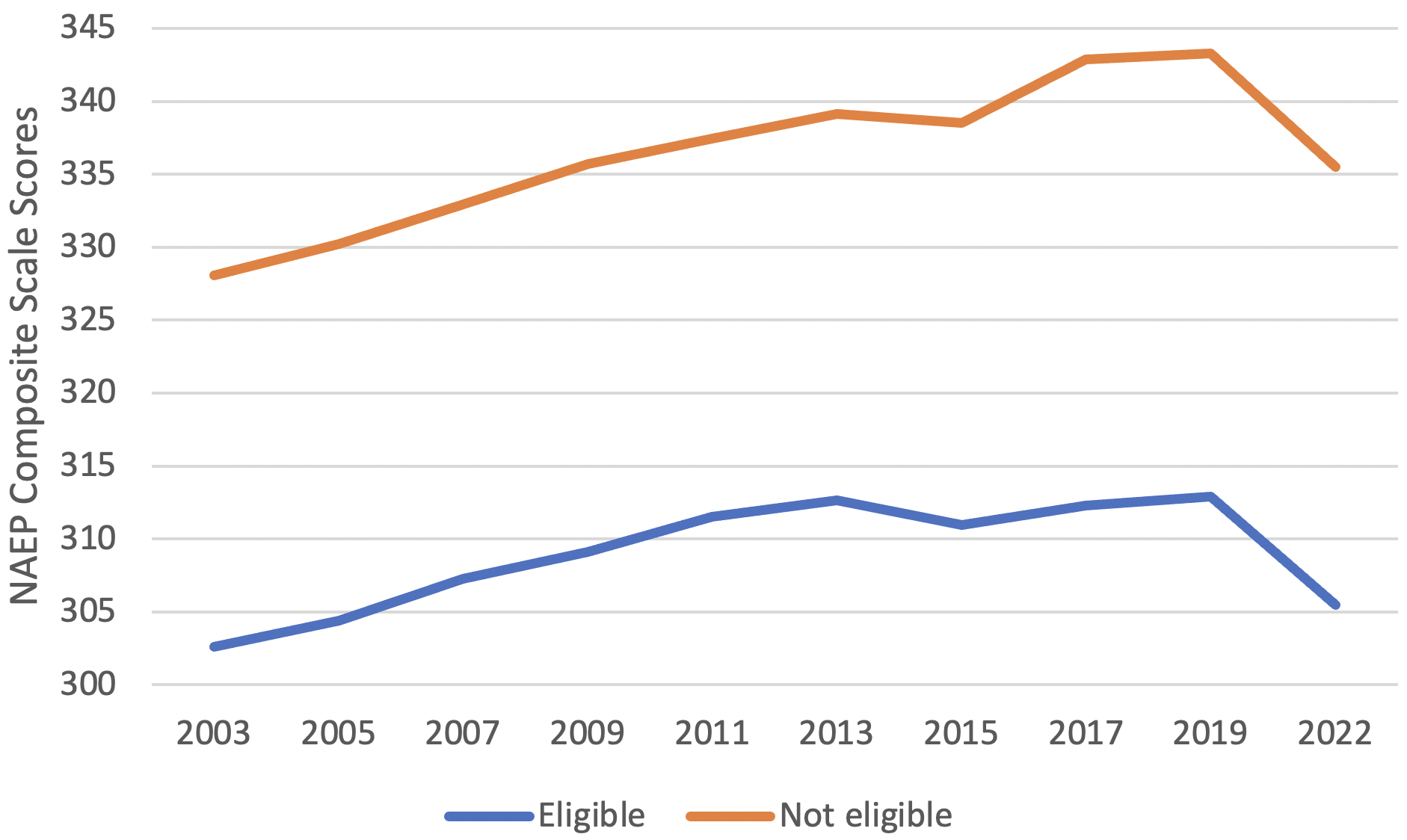

Moreover, these drops were suffered by all racial and ethnic groups, as well as students eligible and not eligible for free and reduced-price lunch. (See figures 3 and 4.) For marginalized eight graders especially, these drops represent something truly alarming. It’s terrible news, for example, that our highest-achieving Black and Hispanic middle schoolers saw dramatic declines in math. Because of this, just 8 percent of Black students are now at NAEP’s “Proficient” level in 8th grade math, and 1 additional percent are at “Advanced.” In other words, most of the highest-achieving Black students in the country—the talented tenth, as W.E.B. Du Bois would have called them—haven’t reached NAEP’s top level, and one in ten aren’t yet to “Proficient.”

Figure 3. NAEP 90th percentile composite scale score, eighth grade math, by race and ethnicity, 2003–22

Figure 4. NAEP 90th percentile composite scale score, eighth grade math, by eligibility for free and reduced-price lunch, 2003–22

The magnitude of the NAEP declines for students in general is going to get a lot of attention. And that attention is, in many places, likely to be of the triage variety, wherein school systems will be tempted to focus almost exclusively on the worst-off students, and to dismiss losses at the high end of the achievement spectrum. And although those at the bottom end absolutely deserve heaps of extra support now and in the coming years, leaders ought to avoid the mistake of assuming that higher achievers will be fine without help of their own.

That’s because considerable research suggests that “math skills better predict future earners and other economic outcomes than other skills learned in high school,” and as the Wall Street Journal reported this week, “math proficiency in eighth grade is one of the most significant predictors of success in high school.” This suggests that the huge drops shown on the Nation’s Report Card over just the past three years could reverberate through the rest of these students' lives, and our country’s future.

This is a problem for at least two reasons. The first is obvious: All students deserve educational experiences that help them reach their full potential, and the experience of these students has fallen well short of that. This is especially true for those who are Black, Hispanic, low-income, and come from other underserved backgrounds. They often depend more on the school system to cultivate their potential and accelerate their performance than their more advantaged peers. And they stand to be most harmed by these massive math losses.

The second argument is that the country needs its high-achieving children to be well educated to ensure its long-term competitiveness, security, and innovation. They’re the young people most apt to become tomorrow’s leaders, scientists, and inventors, and to solve our current and future critical challenges. Indeed, economists don’t agree on much, but almost all concur that a nation’s economic vitality depends heavily on the quality and productivity of its human capital and its capacity for innovation. While the cognitive skills of all citizens are important, that’s especially the case for high achievers. Using international test data, for example, economists Eric Hanushek and Ludger Woessmann estimate that a “10 percentage point increase in the share of top-performing students” within a country “is associated with 1.3 percentage points higher annual growth” of that country’s economy, as measured in per-capita GDP.

One solution, then, is to ensure that, going forward, these children get the services they need to recover from these pandemic-related losses and thrive in high school and beyond. And due to their high achievement, ability, or potential, these students will require something more than can be provided in the average classroom geared toward the average student. Schools should therefore offer distinctive and high-quality advanced programs and services for those who would benefit from them. Where these already exist, don’t cut them; support and maintain them. And where they don’t exist, add them. The future of millions of students, as well as the future of our nation, may depend on it.

—

QUOTE OF NOTE

“Said a former gifted-and-talented student, placed at a large district middle school by lottery, ‘I feel like I’m ready to run a marathon, but my teachers will only let me walk.’”

—“Restore admissions screens for preteens,” New York Daily News, Casey Cohn, October 25, 2022

—

THREE RECENT STUDIES TO STUDY

“Equitable Identification of Gifted Students With the Relationship of Religiosity and Ethical Sensitivity Level of Teachers,” by Hyeseong Lee, Martha A. Wilkins, and Ann O’Brien, Gifted Education International, OnlineFirst, October 17, 2022

“As teachers are the gatekeepers in identification procedure, it is crucial to understand how teachers’ openness and beliefs may affect the equitable identification. To be specific, we focused on how teachers’ level of religious beliefs and ethical sensitivity impact notions of fairness in the identification of gifted students, particularly those from traditionally underrepresented groups. Study participants were 46 teachers who attended a Midwestern Catholic University in the U.S. Based on the results measuring teachers’ religiosity, ethical sensitivity, and equitable identification index from vignettes, we found that there were no statistically significant score differences of religiosity and ethics level of teachers when they were divided into two groups, one showing equitable identification versus the other comparatively not...”

“A Renewed Call for Disaggregation of Racial and Ethnic Data: Advancing Scientific Rigor and Equity in Gifted and Talented Education Research,” by Glorry Yeung and Rachel U. Mun, Journal for the Education of the Gifted, Volume 45, Issue 4

“Researchers in gifted and talented education (GATE) have increasingly taken on the role of advocating equity and access for minoritized populations. However, subgroups of racially and ethnically diverse students are rarely disaggregated from monolithic racial and ethnic categories. Studies on academic achievement of Asian American and White students, based on aggregated data, risk straying from scientific rigor and may lead to conclusions that further contribute to the masking of inequities and disparities of nested subgroups... We contend that fair and equitable access should be afforded to all students and call for the normalization of racial/ethnic data disaggregation in GATE research to increase scientific rigor in our scholarship and unmask intra-ethnic inequities.”

“Validity Evidence of The HOPE Scale in Korea: Identifying Gifted Students From Low-Income and Multicultural Families,” by Hyeseong Lee, Marcia Gentry, and Yukiko Maeda, Gifted Child Quarterly, Volume 66, Issue 1, 2022

“The underrepresentation of students from low-income families and of culturally diverse students is a longstanding and pervasive problem in the field of gifted education. Teachers play an important role in equitably identifying and serving students in gifted education; therefore, the Having Opportunities Promotes Excellence (HOPE) Scale was used in this study with a sample of Korean elementary school teachers (n = 55) and their students (n = 1,157). Confirmatory factor analysis and multigroup confirmatory factor analysis results suggested the HOPE Scale shows equivalence of model form, factor loading, and factor variances across different income and ethnic groups...”

—

WRITING WORTH READING

“Restore admissions screens for preteens,” New York Daily News, Casey Cohn, October 25, 2022

“Massachusetts lacks the talent needed to support its economy. Education could fix that.” Boston Globe, Kara Miller, October 25, 2022

“Bring back selective admissions? some N.Y.C. middle schools say no,” New York Times, Troy Closson, October 24, 2022

“Why universal screening is a more equitable identifier of gifted and talented students,” eSchool News, Anna Houseman, October 24, 2022

“A Brooklyn school's students fought to add AP African American Studies to their curriculum,” NBC News, Janelle Griffith, October 23, 2022

“How high achievers are their own worst enemy,” KWQC, Debbie McFadden, October 18, 2022

“How to raise a high-achieving student: 7 tips from parents of CNY National Merit honorees,” Syracuse.com, By Lindsay Kramer, October 13, 2022

“From 1966 to now, Peoria's gifted program a continuing success in education,” Journal Star, Leslie Renken, October 11, 2022

“Record high for Mississippi Advanced Placement participation, achievement,” The Daily Leader, Daily Leader Staff, October 4, 2022