International student assessments are commonplace today, though none existed before 1965, and few countries participated at the outset. Seven countries have participated in international assessments for almost sixty years—Australia, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, and the United States—and one of the lessons we learn from them is that education is correlated with economic growth. As schooling levels and academic achievement rose, so did national income.

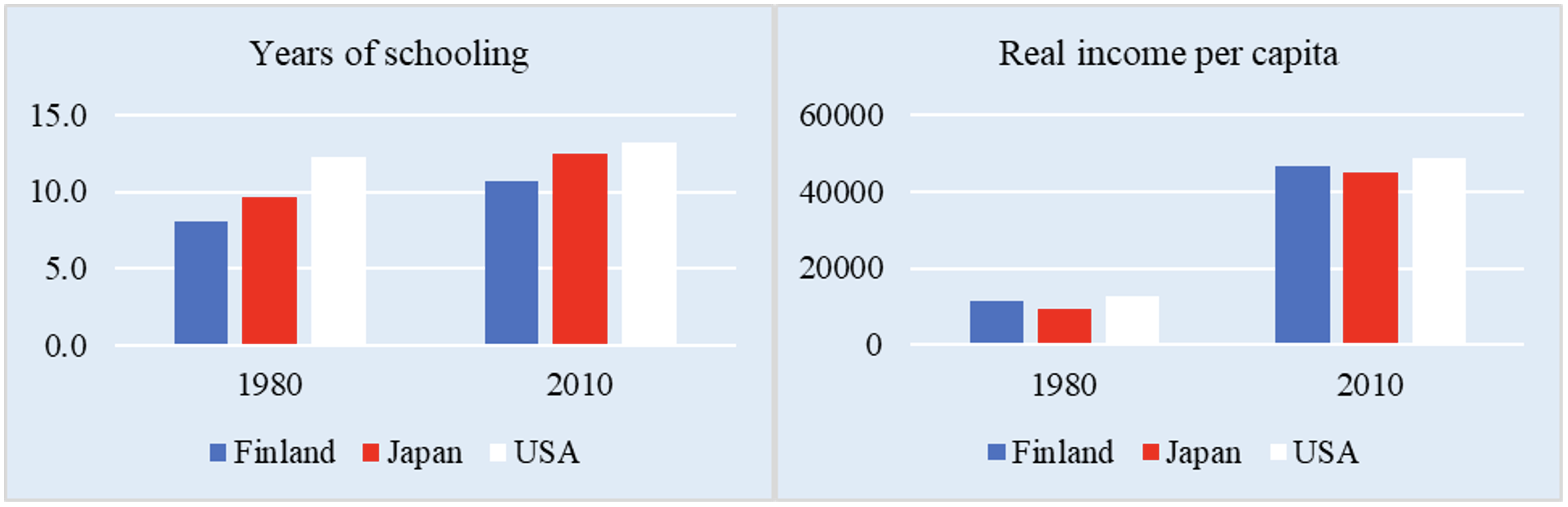

We see in Figure 1, for example, that this in the case of Finland, Japan, and the United States.

Figure 1. Years of schooling and real income per capita for Finland, Japan, and the U.S., 1980 and 2010

Source: Barro, R. and J.-W. Lee. 2013. “A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World, 1950-2010.” Journal of Development Economics 104: 184-198.

One of the likely reasons for this correlation is that economic growth and development considerations mattered deeply for many of these countries. Finland was a middle-income country at the outset. Germany and Japan were in a post-war boom; and then Germany had to reintegrate its Eastern part. These economies needed a skilled workforce to grow.

Therefore, policies to expand skills were undertaken. This caused, among other things, schooling levels to double between 1950 and 2010, according to the same research on which Figure 1 is based. On average, they rose from six to twelve years. Over this period, schooling levels almost doubled in Finland and France. Average years of schooling for all seven countries increased, and at the same time, the differences among them narrowed. Finland expanded the fastest with a focus on access and equity, starting with comprehensive schooling reforms in the 1960s and 1970s that included a gradual transition to a common, unified, compulsory curriculum, with track selection postponed to age fifteen or sixteen. This coincided with the expansion of secondary schooling in the late 1980s. Moreover, the disparity between countries in terms of schooling decreased. Schooling levels have become much more equal across them.

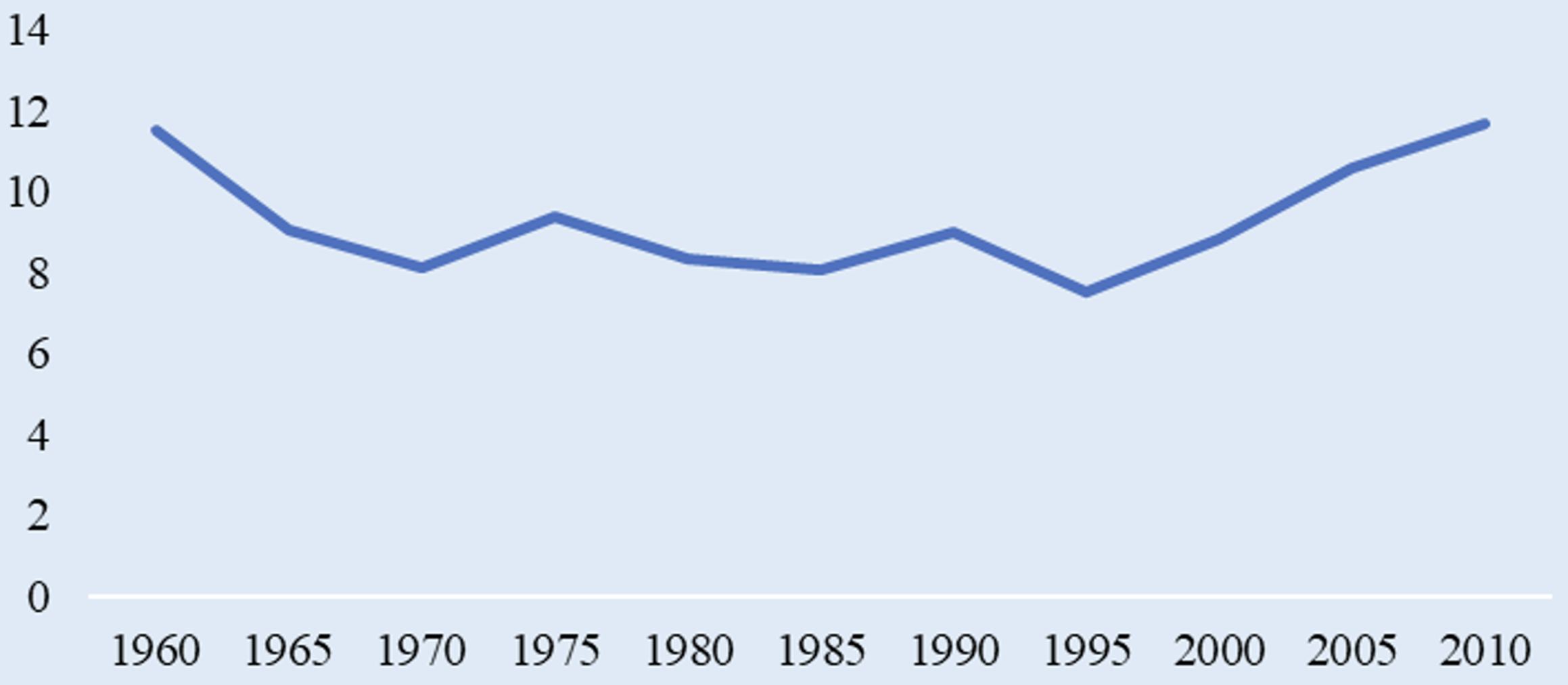

The results were significant, as Figure 2 shows, with the rate of return to investment in education—meaning the costs and benefits both for individual students and for each country as a whole—uniformly high in the seven countries. This can be interpreted as a rise in the demand for skills and a supply source unable to match it. In 1960, the returns on investment range from 10.4 percent in France to 14.0 percent in Australia. As schooling expanded, the returns slowly declined, consistent with economic theory. By 1995, the average returns to schooling were just 7.5 percent. However, those returns begin to rise in the 1990s and remained high into the 2000s, reaching 11.5 percent in 2010.

Figure 2. Average returns to schooling for Australia, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, and the U.S., 1960–2010

Source: Montenegro, C.E. and Patrinos, H.A., 2021. A data set of comparable estimates of the private rate of return to schooling in the world, 1970–2014. International Journal of Manpower; Psacharopoulos, G. and H. Patrinos. 2018. Returns to investment in education: a decennial review of the global literature. Education Economics 26(5): 445-458.

While high returns despite high levels of schooling suggest growing inequality, they also point to demand for skills. Employers value education and are willing to pay for it. The countries examined here valued education and expanded it, and—for a considerable time—improved its quality. The quality of schooling and its expansion raised incomes, reflected in national economic growth and high personal returns.

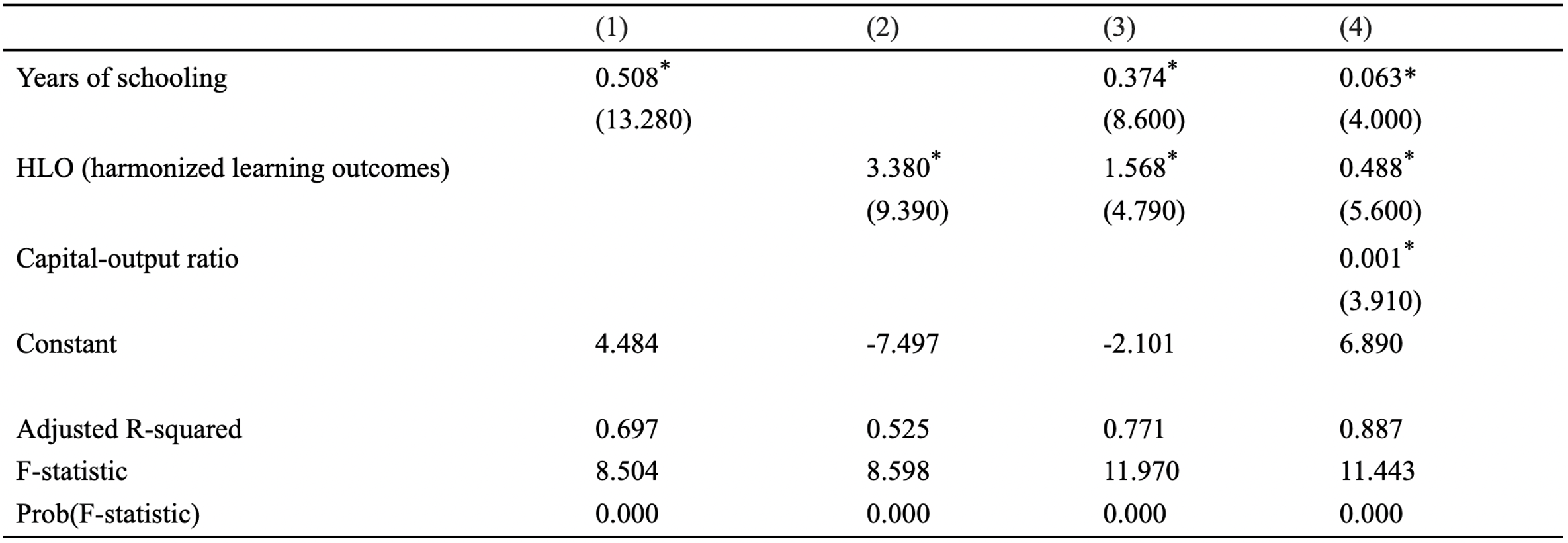

In terms of national income growth, the impact of schooling is significant and large. As Table 1 shows, applying a simple regression model using panel data on the seven countries yields significant coefficients for schooling. On its own, years of schooling has a large, positive effect on GDP per capita over time. When estimating the effect of a measure of school quality—the harmonized learning outcomes (HLO) score (see a fuller definition here)—the effect is even larger. When observing both at the same time, it appears that quantity and quality of schooling matter to a large extent, but that quality matters more. In panel data estimates, schooling is statistically significant even when the regression analysis accounts for the accumulation of physical capital. Moreover, the estimated return to investments in schooling is consistent with those reported in labor studies or other macro analyses.

Table 1. Income level panel estimates: Dependent variable Log GDP per capita, 7 countries, 76 observations, sample period 1965–2015

Notes: Includes country fixed effects but not reported; t-statistics in parentheses. Capital per worker from Feenstra, R.C., R. Inklaar and M.P. Timmer. 2015. “The Next Generation of the Penn World Table.” American Economic Review 105(10): 3150-3182. * Variables signification at 5 percent level.

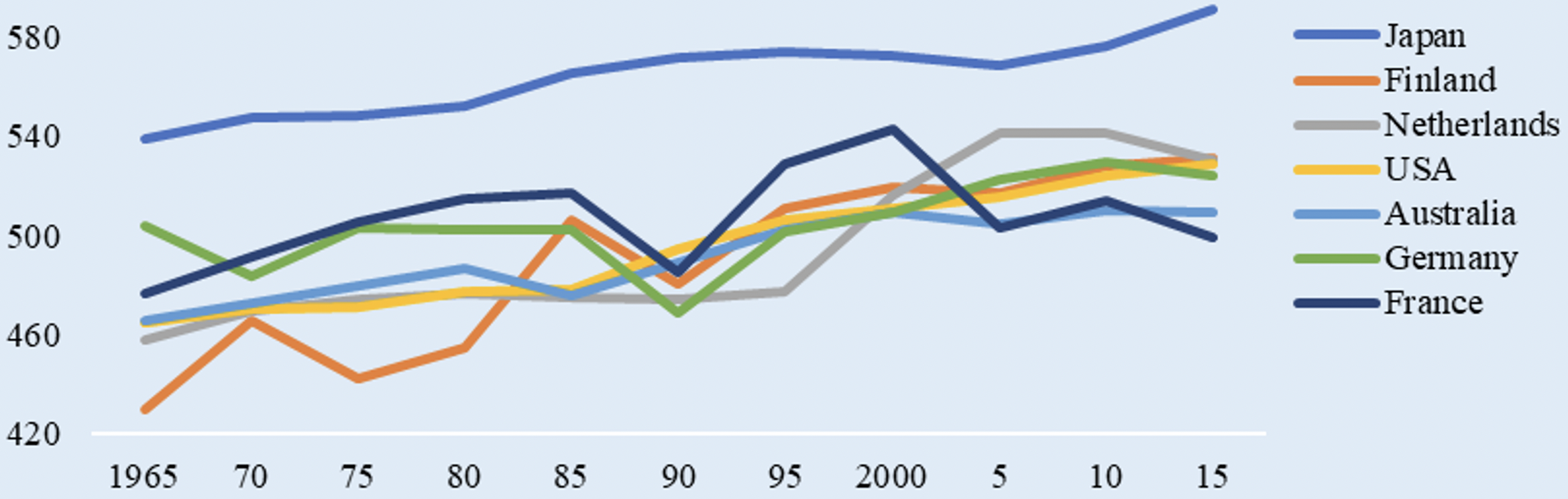

After 2005, however, scores started to diverge. The difference today is almost as high as it was in 1965. Raising schooling levels and sustaining the quality of education are not the same. Long-term convergence in quality is difficult to sustain. Japan is the only country that managed to improve consistently and maintain high learning outcomes since 1965, as Figure 3 shows.

Figure 3. Learning outcomes for Australia, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, and the U.S., harmonized average of reading, math and science scores, 1960–2010

Source: Altinok, N., N. Angrist and H.A. Patrinos 2018. “Global data set on education quality (1965-2015).” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 8314.

Nevertheless, schooling is of high quality in these countries compared to the rest of the world. The fact that quality matters in such countries shows just how important skills are for development. These high-performing, high-income countries focused on schooling to generate resources, and these efforts were correlated with significant returns. In other words, schooling, especially the quality of schooling, is a necessary component of economic growth.