For at least a decade, schools have been using online credit-recovery (OCR) courses to award bogus credits that satisfy graduation requirements, and thus inflating graduation rates. In spite of well documented abuses and comprehensive research studies showing negative outcomes associated with OCR use, schools persist in using them to push students—often the most disadvantaged—across the finish line.

The pandemic made this worse by ushering in a practice that is ripe for cheating: schools allowing students to take OCR courses entirely at home. Worse, some school systems have continued the practice post-pandemic, including three of the largest school systems in my home state of Georgia: Atlanta, Fulton, and Gwinnett.

I recently undertook substantial efforts to confront the problem in my own district (documented in this video), the Paulding County School District, which revealed a massive failure of accountability that may have implications outside of Georgia.

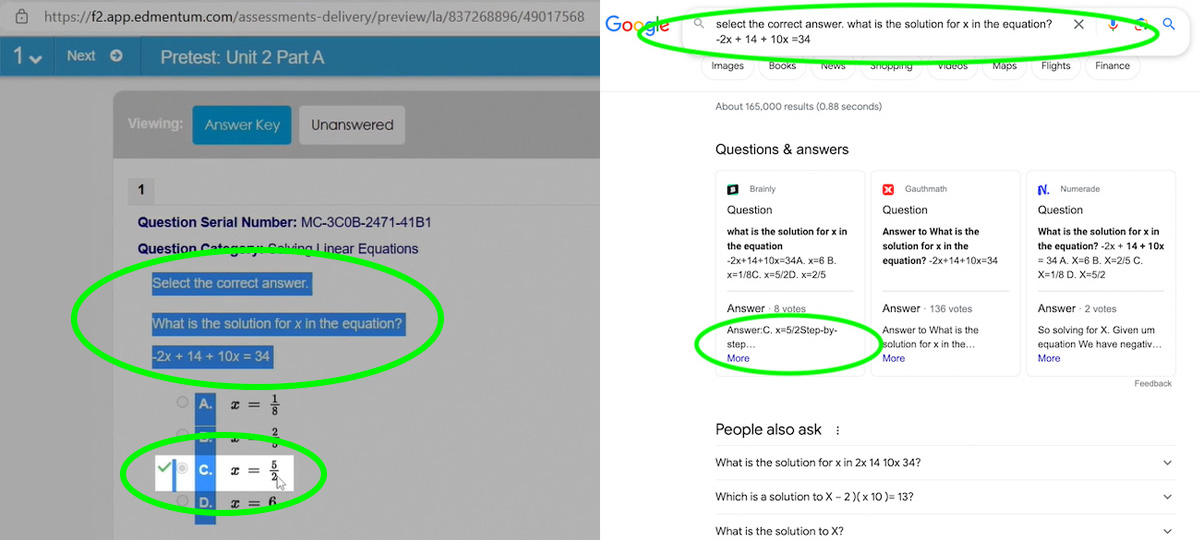

My experience began when I was unexpectedly assigned mid-year to oversee online credit recovery courses. I soon discovered that a few seniors assigned to me never showed up for class and were taking their course at home so they could graduate on time. I was expected to give them access to their assessments by unlocking them on Edmentum’s (the course provider) teacher platform. Knowing that the answers to the test bank were posted on third-party websites in a massive crowd-sourced cheating effort (see Figure 1), I refused to supervise these students and commenced my mission to rid the district of this ill-advised and harmful practice.

Figure 1. An example of how easy it is to cheat on Edmentum’s online credit-recovery courses

I first appealed to my school principal, urging that OCR exams be supervised on campus. But he rejected my proposal on grounds that the practice was a district norm. My first dead end.

Next I contacted my district administrators, but they sanctioned the practice and would not require exams to be proctored. A second dead end.

Realizing that this wasn’t going to be fixed internally, I made a video documenting the cheating and followed my own ethical obligations to report it to outside authorities.

I began by calling the U.S. Department of Education’s fraud, waste, and abuse hotline. For the agency to have jurisdiction, the program must be federally funded. I had reason to believe that Covid relief funds may have been used, but could not verify this. The U.S. DoE declined to get involved, but referred me to Georgia’s state education agency. A third dead end.

I contacted the state DoE’s Accountability Division, whose mission is “to provide all stakeholders with important information on the performance and progress of Georgia schools,” which it does mainly in the form of a school rating system in which graduation rates comprise 10 percent. Since the division’s mandate is limited to measurable outcomes, and not the means by which a school attains them, staff demurred and referred me to the agency’s External Affairs division. There I got some traction, bringing the matter to the attention of officials at the highest levels, but no action was taken. This may have been because, under Georgia’s “Strategic Waiver Initiative,” the DoE has permitted local school boards to waive all sorts of state regulations, provided that they attain certain annual increases in their district’s ratings. Either way, it was my fourth dead end.

I then turned to the Governor’s Office of Student Achievement, which exists to support “accountability and transparency through strategic data use to advance student success.” Since it has a legal mandate to “inspect academic records” to ensure that schools are “faithful to performance accountability requirements,” I requested an academic audit of the Paulding County School District’s credit recovery program. But their mandate extends only to standardized assessments required by the state. Lacking the authority to investigate local assessments, they also declined to get involved. A fifth dead end.

My next step was Cognia, the non-governmental accreditors that are supposed to ensure that accredited online courses are effective and credible, which would include verifying that the assessments are valid, i.e., not gameable. Cognia’s current president distinguishes the purpose of accreditation from that of government accountability: “unlike compliance measures, accreditation identifies what graduation rates, test scores, and other indicators cannot tell on their own—what takes place in the school that leads to its results.” In other words, accreditation focuses on the means by which an increased metric is attained. Since enabling online cheating betrays public trust and obliterates the credibility of academic credits, I assumed Cognia would get involved, so I filed a complaint supported by extensive documentation.

But Cognia sent an email to the Paulding County School District about my complaint, explaining that the accreditor was declining to investigate due to “insufficient evidence.” This was surprising, considering that I was a first-hand source who gave them email evidence of the district’s approval of unsupervised testing, as well as multiple assessment-provider records showing how students aced tests in impossibly low amounts of time.

Cognia, it seems, has been enabling schools to engage in such practices for over a decade by giving OCR courses its stamp of approval, in spite of the various ways they fall short of basic accreditation standards. Accrediting ineffective and easily gameable courses should damage Cognia’s credibility. But that doesn’t seem to have happened. A sixth dead end.

The last institution I could think of that may have the power and will to bring some accountability was Georgia’s Professional Standards Commission (PSC). The PSC oversees teacher certification, and is charged with enforcing the state’s ethics code.

Of the ten standards that comprise the code, two seemed germane to this scheme: honesty and professional conduct. Honesty is violated when schools misrepresent student achievement. Professional conduct is a catch-all category for any number of behaviors that are detrimental to education and to the “welfare or morals of students.” (There is a third standard on test integrity, but this is only limited to state-mandated assessments. When it comes to the integrity of local assessments in Georgia, anything goes.) Enabling students to earn graduation credits fraudulently certainly misrepresents student achievement and harms the profession while damaging students’ consciences.

Alas, the PSC complaint form is focused on discrete violations by specific individuals and is not set up for reporting systemic cheating where administrators are complicit for creating a permission structure, and guidance counselors and teachers are complicit for carrying out the scam by unlocking tests knowing that students had access to the answers. My seventh and final dead end.

—

One of the largest cheating scandals in U.S. history unfolded from 2009–2011 in Atlanta Public Schools, when over 100 educators were implicated in changing students’ wrong answers on state-mandated assessments A few were sentenced to prison. (The Fulton County District Attorney who indicted Trump last week was the lead prosecutor!) There were severe consequences because there are definitive regulations for state-mandated assessments and clear sanctions for cheating. Educators thus take great pains to administer these tests with integrity.

Yet when it comes to increasing graduation rates, rightly called the most “fungible statistic in education,” educators can practice—or allow their students to practice—all sorts of gaming behaviors with impunity because they are held accountable by the state only for the outcome. Online-credit recovery is a prime example of this.

To deter this behavior, we need a better system that also holds everyone—education departments, accreditors, administrators, principals, and educators—accountable for the means, as well. Yes, it’s vital that more high school students earn diplomas. But those diplomas will become worthless unless they mean that graduates are prepared for college and career.

Some of Georgia’s largest school systems fall short of this standard—and that’s very likely true of many more across the country. The biggest victims are the students themselves, failed by their schools and thrust into adulthood with false promises and a lack of skills. It’s high time for our leaders to put these young people first.

Editor’s note: Jeremy Noonan resigned his teaching position in Paulding County after the district refused to address the problem. In response to an Atlanta Journal-Constitution article and video based on his experience, he was put on paid administrative leave in order for the district to conduct their own ethics investigation into his use of student data.