“From Bat Mitzvah to the Bar: Religious Habitus, Self-Concept, and Women’s Educational Outcomes,” a new study by Ilana Horwitz et al., analyzes the college-going rates of women raised by Jewish versus non-Jewish parents. Its findings shed light on how religious subgroups incubate certain habits of minds and practices that influence educational outcomes.

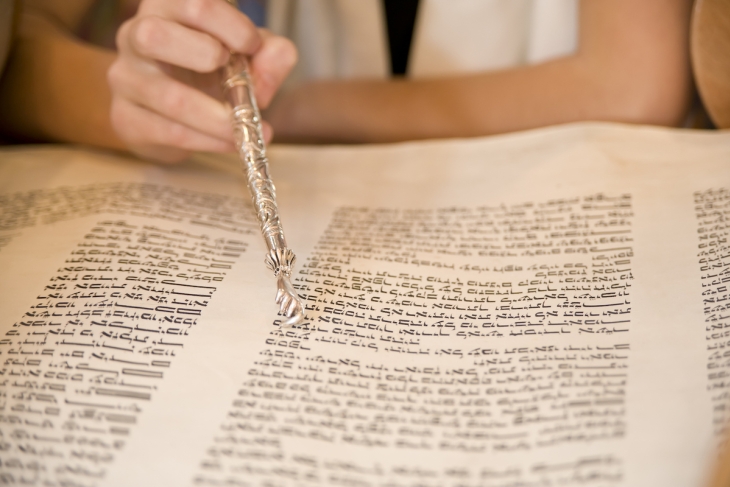

Horwitz—an assistant professor in the Department of Jewish Studies at Tulane University—has previously written about religious affiliation and college. Earlier this year, she published God, Grades, and Graduation, which examined the college-going rates of devout Christian teens compared to their more secular peers. The title of her newest article contains a reference to the coming-of-age ritual undertaken by Jewish women at age thirteen. While its male equivalent—the bar mitzvah—goes back to the Middle Ages, the bat mitzvah is of recent vintage. It was not until 1922 that the first bat mitzvah was performed at a New York synagogue—a particularly American blend of tradition and egalitarianism.

Horwitz’s team analyzed three sets of data: the National Study of Youth and Religion (NSYR), the National Student Clearinghouse Survey (NSCS), and qualitative interviews with students as they matured from middle school girls into college women. The NSYR is a four-wave longitudinal study of children ages thirteen to seventeen. Participants—and their parents—were asked a series of questions about their social, academic, and religious lives from 2002 to 2013. The NSCS is used to gather detailed information about college admission and graduation rates. These quantitative data were complemented by information gathered from 107 interviews with thirty-three respondents.

The study considers two dependent variables: the attainment of a bachelor’s degree by 2016 and the selectivity of the undergraduate institution attended by the respondent. Selectivity is determined by the average SAT score of an institution’s admitted students. The key independent variable is the respondent’s religious upbringing, which is separated into three categories: raised by one Jewish parent; raised by two Jewish parents; and raised by non-Jewish parents. Other independent variables—such as gender, socioeconomic status, parents’ occupational prestige, and family income—are used to more fully account for the respondents’ backgrounds.

Horwitz finds that children of any gender who were raised by at least one Jewish parent had a 52 percent predicted probability of attaining a bachelor’s degree, compared to 34 percent of children raised by non-Jewish parents (controlling for variables like socioeconomic status and parents educational attainment). The effect becomes stronger if children were raised by two Jewish parents: while children raised by one Jewish parent[1] have a 46 percent predicted probability of bachelor’s degree attainment, children raised by two Jewish parents have a 58 percent rate.

As suggested by the article’s title, the effect is most pronounced for women. Women with any Jewish upbringing (one or two parents) have a 59 percent predicted probability rate of bachelor’s degree attainment. That rate is 37 percent for their peers with no Jewish upbringing.

The effect of Jewish upbringing is also seen in the selectivity of the colleges attended by the respondents. Respondents of any gender with no Jewish upbringing attended colleges where the average SAT score for admitted students was 1084. For respondents with one Jewish parent, it was 1123, and for respondents with two Jewish parents it was 1152. For women, those with any Jewish upbringing attended colleges where the average SAT score was 1139. It was 1084 for women with no Jewish upbringing.

Why would being raised by Jewish parents make a difference in a child’s educational attainment? This advantage was present even when the study controlled for variables such as parents’ incomes, occupations, and other aspects of socio-economic status. Horwitz is quick to point out that the origin of these effects cannot be found in a genetic or racial difference between Jews and non-Jews. Instead, she proposes that the habitus of Jewish families contributes to these results.

Habitus—a term pioneered by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu—refers to a person’s mental habits, dispositions, and practices. They are modeled and reinforced during a child’s process of socialization by parents, extended family members, and other adults in the community. Horwitz traces the habitus of American Jewish families through the centuries to ancient and medieval Europe. Traditional Jewish observance required intense study of texts such as the Torah and Talmud, meaning that literacy was an essential part of religious practice at a time when most people could not read or write. It was also typical for Jews to be barred from farming, skilled trades, and other professions by non-Jewish political authorities. This led to Jews adopting professions that required knowledge of words and numbers. After the emancipations of the Enlightenment, European Jews brought this habitus of literacy with them to America.

Through the longitudinal interviews, Horwitz’s team also finds a difference in habitus concerning roles for women and girls’ concept of their future selves. The women who were raised by at least one Jewish parent were more likely to articulate a vision of their future that centered on professional prestige. They were also more likely to have a plan to attain this prestige, which almost always included graduating from a selective university. Motherhood, while seen as desirable, came after college and career on the list of priorities. Women from non-Jewish households were more likely to prioritize marriage and family. They were also less likely to place a high importance on attending a selective college.

In the discussion section of the article, Horwitz argues that “stratification scholars should pay more attention to religious subcultures as a central factor in educational stratification.” This advice has not gone unheeded. In his new book, Ian Rowe argues that religion is essential to helping children—especially those from underprivileged backgrounds—thrive socially and academically. Timothy Carney explored the breakdown of religious institutions and its negative effects on life outcomes in Alienated America. The work of all three authors should motivate us to take a closer look at the interplay of religion and education.

SOURCE: Horwitz, I. M., Matheny, K. T., Laryea, K., & Schnabel, L. (2022). From bat mitzvah to the bar: religious habitus, self-concept, and women’s educational outcomes. American Sociological Review, 87(2), 336–372.

[1] For this study, the category of “raised by one Jewish parent” included participants raised in two-parent households (one Jewish and one non-Jewish) and one-parent households. Horwitz states that analyses of these two sub-groups yielded “equivalent results.”