Editor’s note: This is the third in a series of posts looking at how two school networks—Rocketship Public Schools and Wildflower Schools—enable their students to meet standards at their own pace. See the first two posts here and here.

Last week, we examined how Wildflower and Rocketship ensure that their efforts to tailor instruction to individual kids don’t end up lowering the bar for their struggling students. Both schools are fully committed to making sure all of their charges meet academic standards so they are well prepared for life and further learning. They just don’t think students should have to march through the curriculum in lock-step.

This week, we’ll look at the other end of the performance spectrum: the schools’ high achieving students. For such kids, personalized pacing seems to come with nothing but upsides—unless you oppose in principle any kind of individualized instruction for “gifted” students, as some in New York City apparently do. At Rocketship the focus is on “acceleration”; Wildflower, a Montessori model. is more about “enrichment.” Let’s take a look.

Rocketship’s Preston Smith:

At Rocketship Public Schools, we serve all students with excellence—no matter how far behind or ahead they are when entering our schools. We meet each Rocketeer’s individual needs through our personalized learning model and see tremendous academic growth at all levels of achievement. In our schools, all students have the ability to move beyond their grade level materials through their individualized learning and small group time in each subject. This happens in online learning programs and individual reading and work time, usually through next-level assignments.

During our “guided reading,” for example, Rocketeers are grouped by reading levels that are sometimes at the “next grade” and led by their teacher. For those Rocketeers who are at even higher levels, we may have them participate in a guided reading group at another, higher grade level with a different teacher who may have greater mastery with particular reading levels. We use STEP (a reading assessment developed at the University of Chicago), which levels students for all reading materials and skills. Furthermore, STEP allows our Rocketeers to take ownership of their reading goals, always knowing which STEP level they are at and how to progress to the next. When students advance, even if the next level is technically aligned to a higher grade, the student can always access books at this level and immediately begin reading. Moreover, by having flexibility in classroom groupings, these Rocketeers can always access a teacher with the expertise to help them continue to master the skills required at their current reading level. This helps to prevent any backsliding in reading skills.

Similarly, in STEM, we have small group instruction time, where a teacher can regularly “extend” a lesson or content area (either in person, via independent assignments, or online programs) and ensure that high achievers are gaining access to and mastery of content at the next grade level.

We strongly believe that it is important to challenge students at all times and help them feel engaged in their learning, so we make sure all students have the appropriate materials for their individual learning level and to extend beyond.

Wildflower’s Matthew Kramer:

There’s pretty compelling anecdotal evidence in the form of the many extraordinary people who credit their time in a Montessori environment as a significant reason for their development. We see this in the choices that people with many options make about the school model for their own children, and in the recommendations conventional teachers frequently make to families looking for more challenging environments for academically successful but bored children.

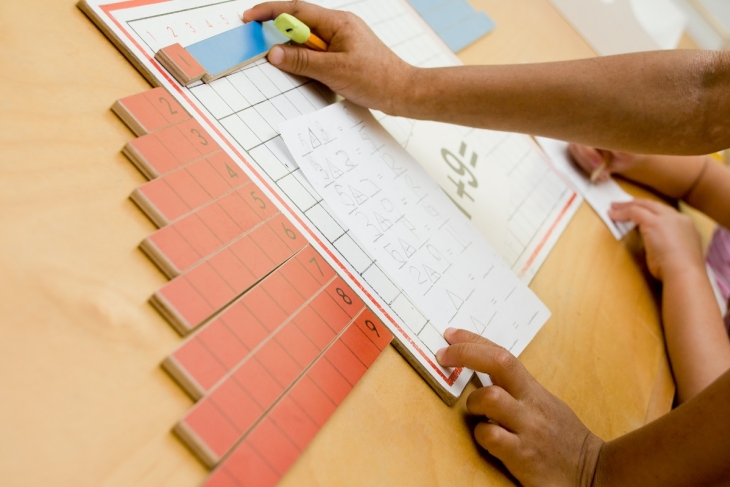

One way to think of the Montessori curriculum is as a series of basic introductions to various ideas and skills that lay the groundwork for a wide variety of independent explorations. For example, a group of lower elementary children might be shown how to multiply three-digit numbers by two-digit numbers using the Montessori multiplication checkerboard—an iconic Montessori math manipulative. Doing this multiplication involves meticulously following a detailed, multi-step algorithm. If two children receive the same presentation, one might immediately take to the work and make up a list of twenty-five such problems and spend hours working through them independently, carefully writing their answers, and making a bound book out of it that they share with others. The other might take to it more slowly, spending several hours working through a single problem, making mistakes, realizing those mistakes through the material’s built in control of error, and asking a friend for help.

This pattern plays out across a range of topics. A presentation on early humans could lead to a brief report on the subject, or it could lead to a multi-week investigation involving multiple children, student planned and executed trips to a natural history museum, direct outreach to a working paleoanthropologist, in depth research using the internet or the library, a twenty-page report, and a whole-class presentation.

Because the topics introduced in Montessori represent an age-appropriate tour of the whole of human knowledge, there is limitless potential to take a topic and go deep with it, constrained only by a child’s curiosity and the fact that there are always other topics worth exploring around the next bend.