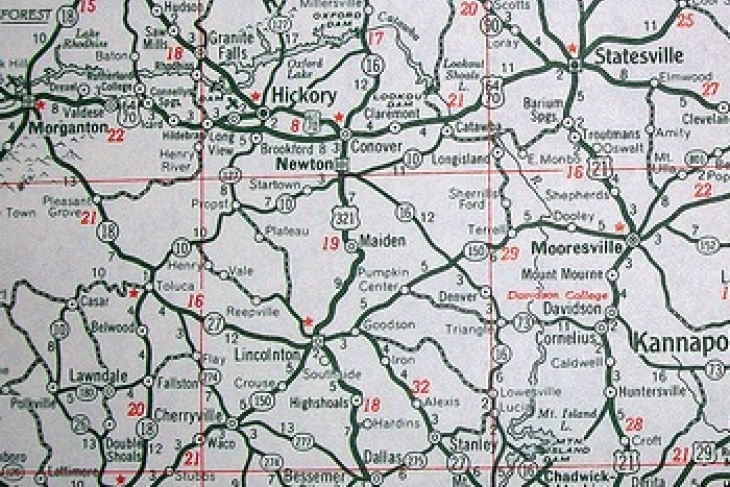

There’s a lot of talk about disruptive innovation these days. It seems hardly a month goes by that we don’t see some sort of exciting new innovation that changes an industry. Sometimes it happens over and over again in the same space. First we had paper maps that were replaced by custom driving directions we could print out from MapQuest (remember those?). Then came some very expensive GPS systems mounted in cars. Those, in turn, were replaced by much cheaper portable GPS systems from companies like Garmin, which were basically made obsolete by free map applications from Apple, Google, and others in nearly all cell phones sold today. All this in a handful of years! Fortunately, paper mapmakers weren’t ultra-powerful on Capitol Hill, or we might still be sitting in our cars trying to figure out how the heck you’re supposed to fold those things.

Unfortunately, the traditional public education system does have an army of apologists, lobbyists and piles of cash to protect itself and resist change. Public unions are the best funded of these anti-change agents, but they are by no means the only players to resist everything from accountability to online learning to charter schools—none of which are really that radical when you think about it.

A white paper published by the Annenberg Institute for School Reform, “Public Accountability for Charter Schools: Standards and Policy Recommendations for Effective Oversight,” follows a familiar path. The ideas, almost certainly by design, would stifle the innovation we are getting from charter schools by bludgeoning them with regulation. If enacted, the recommendations in the report would negate many of the recent advances in school design and utilization that have been enabled by charter flexibility.

Annenberg doesn’t frame it this way, of course. Instead, the authors claim that the charter movement has lost sight of the goals of education reform and that regulatory legislation is outdated, deficient, and in need of reexamination. “Chartering has become an industry,” the report reads, “and in many cases, rapid expansion has replaced innovation and excellence as goals. …State charter laws, regulation, and oversight have not kept up with this changing dynamic.”

In order to shackle their competition (err, protect children), the authors outline seven areas that should be addressed with new oversight:

- Charter and district schools should work in tandem and not as competitors.

- Charters must increase transparency and reorganize power structures in order to diminish the influence of the authorizers and management organizations (in other words, the unions and their allies should have a hand in running the schools so they can keep tabs).

- Admissions and enrollment policies that differ too greatly from those of district schools must be eliminated.

- Charter schools must enact more lenient disciplinary practices.

- Charter and district schools should not compete over resources, and co-located schools must be monitored closely for disparity.

- Online charters must adhere to the same rules and standards as brick-and-mortar institutions, except they should be subject to additional scrutiny as well.

- Oversight of charters must be robust and entirely state funded.

Each section admittedly sounds somewhat reasonable on its face (and Rand McNally might reasonably have suggested we place limits on GPS functionality to prevent distracted driving), but much of the supposed need for reform is based on debunked or exaggerated claims about charter schools that have been around since there have been charter schools—that they discriminate, for example, or cream the best students. Naturally, status quo advocates like those at the American Federation of Teachers jumped out in support, with a statement claiming, “The promise of charter schools wasn’t about competition, it was about communities coming together…that promise can only be realized if charter schools are held to the same standards of accountability and transparency as neighborhood public schools.”

Wrong. Bad charter schools (and distracted drivers) exist and are a serious problem. The AFT and others are within their rights to demand strong outcome-based accountability that treats all schools similarly. Fordham has never been shy about its desire for this type of oversight, and we would gladly welcome AFT’s support. They could also demand that the regulatory burden be leveled by removing barriers on traditional public schools (rather than raising them on charters), but policies like those would remove their artificially created competitive advantage (and don’t forget, they often have a large funding advantage, too! So much for a level playing field). Digital navigation aids, on the other hand, have continued to get better and safer through competition and innovation rather than overbearing regulation (commonsense “texting and driving” bans aside). Meanwhile, the monumental effort companies like Google have put into perfecting their digital maps could one day provide the backbone for autonomous cars that might prevent thousands of road deaths each year.

Our schools are in desperate need of a similar wave of innovation, but Annenberg’s numerous, often overzealous statutory recommendations would only encumber emerging charters and cripple those in existence. For example, requiring online schools to adhere to the same attendance laws as brick-and-mortar schools is a bizarre idea that would marginalize one of the biggest benefits of online study. Furthermore, evaluating online teachers and educators who work within alternative teaching structures under the same systems as other teachers just isn’t practical, as they might be teaching a class of students from multiple school districts or even multiple states.

The Annenberg Institute report does offer some suggestions that could be useful in creating a truly level and competitive playing field. Requiring school attorneys, accountants, and auditors to answer directly to the governing boards and not the management organizations, for example, is an idea worth discussing. However, reasonable ideas are far outweighed by outlandish, restrictive policy suggestions and the all-too-obvious underlying aim of policies like these that have been offered for many years. It’s far past time that status quo progressives stop standing in the way of progress.