Editor’s note: This blog post was first published by Partnership Schools.

School districts across the country are at odds over how to grade students during this national school shutdown. Reasonably so. Any approach we take is mired with limitations and the very real risk of penalizing students unfairly for circumstances well beyond their control.

Whatever the policy, we believe the grades we give students must have integrity. If the grades are to communicate substantive information about learning as students and families deserve and expect, they must be fair, honest, and individualized.

But, by design, grades are a coded shorthand for academic achievement. Grades are not—and cannot be—a stand-in for the precious feedback loop embedded into good classroom instruction.

This constant stream of information is the stuff that learning is really made of. Keeping the feedback loop intact is the only way students know what they have successfully understood and integrated into memory for the long haul, and what they have yet to master.

At Partnership Schools, our teachers are tireless about giving students the meaningful feedback they crave–feedback that relieves the isolation of distance learning, meeting each student where they are to propel their thinking forward. Every day, teachers signal deep engagement in their students’ intellectual work through this intentional feedback.

Education researcher Harry Fletcher-Wood’s recent thread on the impact of explanatory versus correct answer feedback got me chewing on the different ways our teachers craft feedback for students and how they ensure that it is maximally impactful on learning—both inside and outside the classroom.

In short, our teachers frequently use feedback to:

- Praise accuracy and acknowledge errors.

- Cause students to recall knowledge they’ve previously learned and apply it.

- Habituate skills that build student autonomy.

Praising accuracy and acknowledging errors

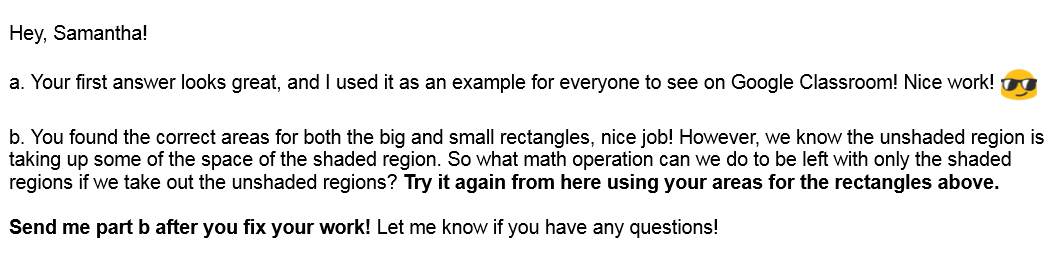

In the example below, seventh grade math teacher Corey Kuminecz praises Samantha’s “exemplar-level” answer, before giving bite-sized, actionable feedback. Corey narrowly draws a manageable “re-do” for the student to ensure they have an opportunity to resolve their error and lock in the skill he wants her to master.

We also loved that Corey leveraged Samantha’s first answer as a sample for the class. This “Show Call” helps students to evaluate their own work independently, while building a celebratory culture around publicly sharing student work.

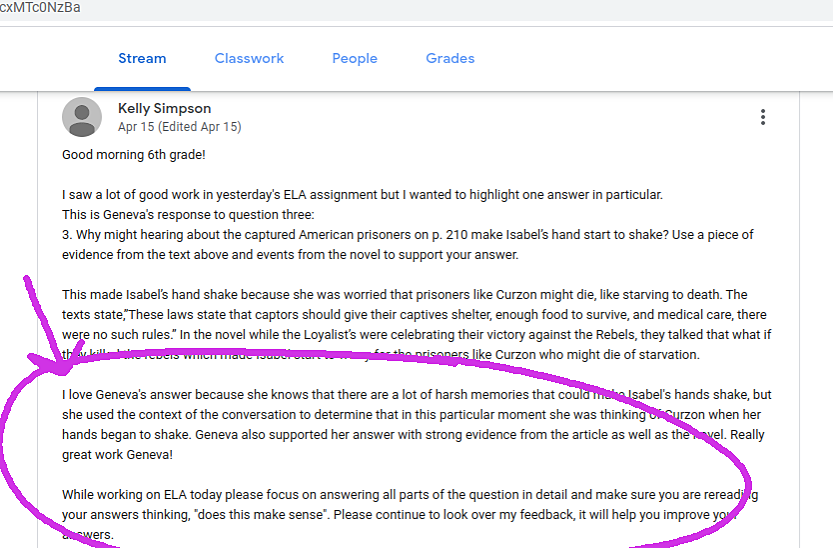

In the example below, sixth grade teacher Kelly Simpson highlights one student’s analysis of a passage from Chains to help set clear expectations in advance of the day’s reading.

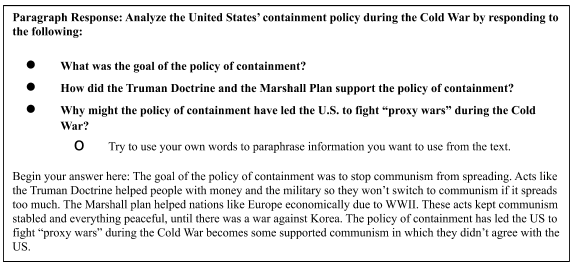

Here’s a final example from eighth grade history teacher and Academic Dean Will Beller. He is intentional about reinforcing the key content knowledge that the student nailed, while also addressing an important nuance about global instability that he wants the student to walk away with.

Here’s the assignment and the student response:

And Will’s feedback:

Excellent careful reading of the article that addresses a new topic. You clearly identify the goal of containment and the way the Marshall Plan and Truman Doctrine were related. You also do a great job of identifying why the nation was involved in “proxy wars”—not everyone agreed with the US or capitalism, which is an important point to remember throughout our study of this unit. Awesome work!

One thing to consider: The Marshal Plan and Truman Doctrine tried to keep things stable, but there was still plenty of instability in the world at this time.

I hope you are enjoying your weekend. Keep up the good work and take care!

Causing students to recall knowledge and apply it

In previous examples, we’ve seen teachers ask students to apply knowledge they’ve previously learned (e.g., “What math operation can we do, to be left with…”).

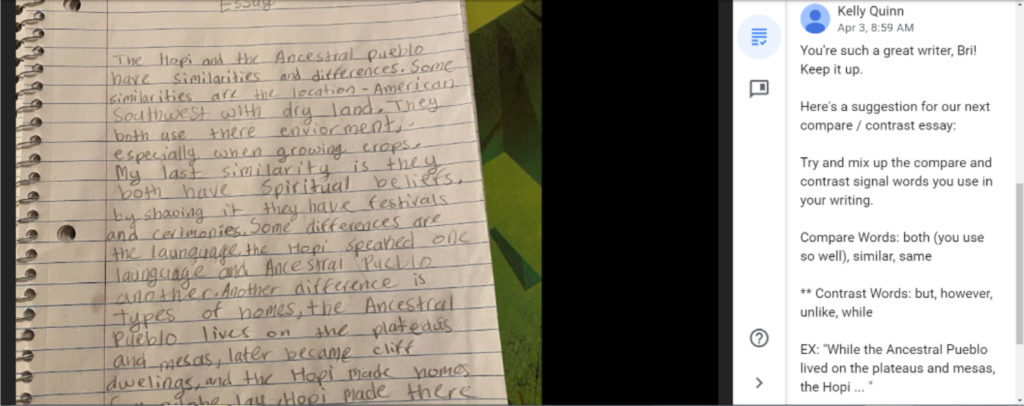

Here is just one more example from third grade teacher Kelly Quinn. Below she reminds a student of language they’ve studied to compare and contrast ideas in their writing. Wisely, she provides a clear model and asks then asks the student revise their writing and apply it.

Habituating skills that build student autonomy

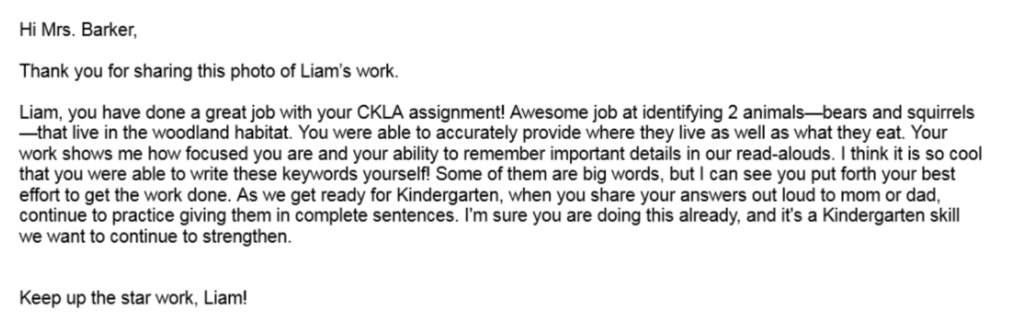

Pre-K teacher Saramarie Colandra proves that even our youngest learners benefit from feedback. Below, Saramarie gives some helpful feedback to Liam via his parents to help him prepare for the classroom discussions he’ll encounter next year. This helps to habituate the skills that’ll be expected of him in the year ahead. And she also provides the feedback in a way that is clear and actionable for his parents to support.

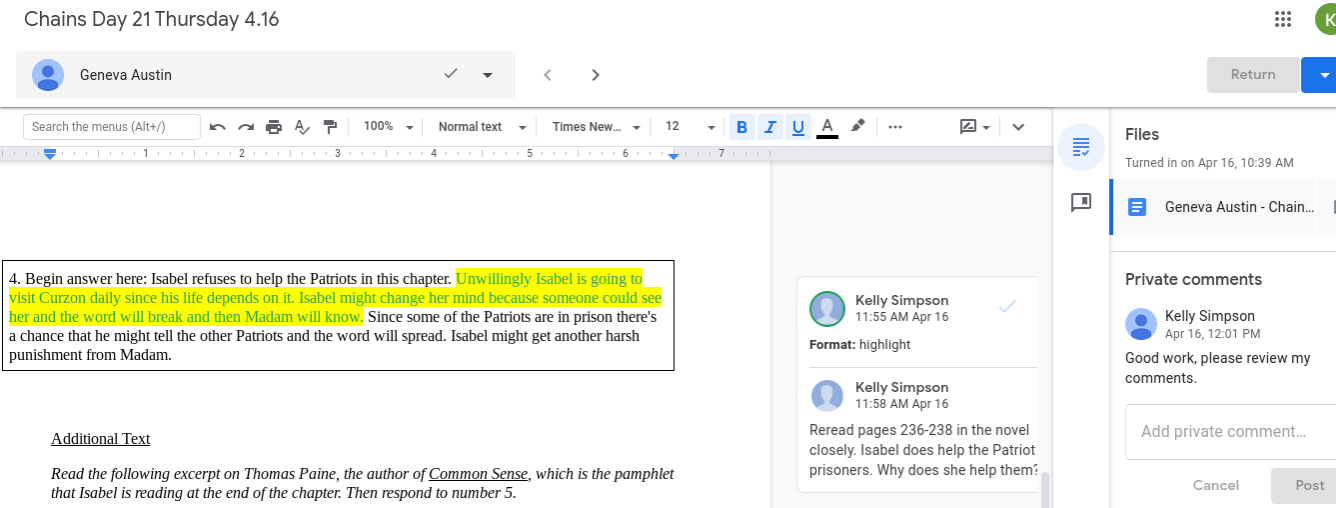

In this final example, Kelly Simpson redirects students back to the novel to reread a key passage for accuracy. Socializing rereading is so critical, especially as students encounter more complex and sophisticated texts in the upper grades. We love how she does this, with a clear focal point to frame the students’ reread.

These examples are just a few of many. Partnership teachers are providing literally hundreds of bits of feedback like this per week. And it’s not just any feedback. It’s thoughtful, carefully wrought feedback that shows they have their finger on the pulse of student learning and know how to push it forward in objective-driven ways.