Jamestown, Valley Forge, the pioneers’ Conestoga wagons, and so much more—the skills of survival are woven into the American narrative. Our heroes include Thomas Edison and Steve Jobs, and today’s national conversation about education focuses on giving students the technical and career-ready competencies that ensure rewarding and fulfilling employment. Our renewed interest in “practical” learning recalls Benjamin Franklin’s sardonic take-down of the academic kind: “He was so learned that he could name a horse in nine languages; so ignorant that he bought a cow to ride on.”

Focusing on skills makes a virtue, too, of America’s heterogeneity. In the England of my own youth, curricula and assessments in the language arts were one and the same: Examiners assigned the texts, teachers taught them, and the exams required students to write about them. That meant teachers never faced such questions as why those texts, those authors, and not these (insert one’s own cultural favorites)? In today’s United States, by contrast, focusing on leaning to master reading skills makes content a secondary concern, one left to choices by teachers, districts, or states. This has a certain, if questionable, logic: Students in Mississippi can be taught about the “War of Northern Aggression” and read As I Lay Dying, while their peers in Massachusetts study the Civil War and The Scarlet Letter. Yet this variability, even agnosticism, regarding the selection of content and texts gives rise to a deep problem: In too many U.S. schools, students spend little time with Faulkner or Hawthorne or carefully reading other whole books. Why should they, when what unifies our educational system is that students across the land will be assessed on their prowess at “finding the main idea” across bits of texts pulled from readings they haven’t read except by chance, of uncovering inferences in the fragments, and of learning random vocabulary words? The assessment-tail wags the curriculum-dog, pressing teachers to drill on those “reading skills,” especially when instructing students who are already behind.

More recently, our enduring focus on skills over content knowledge has received a double boost. Given the explosion of technology and access to information, it feels right to suppose that today’s students need “to learn how to learn,” to “think critically,” rather than mastering specific domains of knowledge. Second, we are told that social and emotional learning (SEL) is as important—some would argue more important—than academics and the results of academic assessments.

A few voices, such as E.D. Hirsch and Daniel T. Willingham, have long cautioned that this is national folly. Even as students are learning to read, which necessarily involves skills such as decoding, their greatest need is to build content knowledge. America’s reading gaps are not caused by skills shortages but by knowledge vacuums. When we provide even very weak readers with a story about a topic they know, finding the main idea is a snap. By contrast, give strong readers a passage about something they know nothing about, and they can stare at it forever with little chance of finding that same idea. As Hirsch recounts in Why Knowledge Matters, detailed data from France show that when that country abandoned its national, content-rich reading curriculum, the performance of all students declined, and the poorer the student, the more precipitous the loss. In the U.S., while we’ve seen reading scores rise in the early grades, NAEP twelfth-grade reading performance remains essentially unchanged from the early 1990s, and the tragically wide racial and socioeconomic achievement gaps show no signs of closing.

As for critical thinking: Try thinking critically about nothing in particular, for thirty seconds. Then, think critically about well-compensated jobs—brain surgeons, airline pilots, petroleum engineers. As you do so, notice the higher-order thinking that’s required of these professionals, but note, too, that it’s entirely based on thousands of hours of accumulated content knowledge. As for SEL, ample evidence suggests two-way correlations: Strong academics and strong SEL reinforce one another, and both correlate to long-term life prospects. Relegating academic content will prove as myopic as trumpeting self-esteem absent real achievement.

Today, we know that most teachers create their class materials by plucking them just-in-time from sites such as Pinterest, Google, and Teachers Pay Teachers. Then they mix their harvest—with little or no support—with fragments of district-provided materials. As a nation, we can do so much better by our children. Following on the strong example of Louisiana, the Council of Chief State School Officers is working with eight states as they plan policies to support the widespread use of high-quality instructional materials. ELA curricula such as EL Education, Louisiana's ELA Guidebooks, Wit and Wisdom, and Core Knowledge Language Arts offer open-education resources and content-rich material aimed at building background knowledge.[1] Creating outstanding curricula and preparing teachers to use it well needs to become the norm across the country.

At the same time, we should build assessments that enable students to answer questions using specific content. For years, the Latin Advanced Placement exam announced the texts it would examine in advance (perhaps they figured that Latin was just so esoteric that no one would notice). More recently, the AP American Literature exam added an essay question that requires students to answer using concrete knowledge of the books they have studied. It is exactly wrong to conclude that such essay questions—which are also asked in the International Baccalaureate—are suited only for the strongest of students. It is our less privileged students who most need the background knowledge that deep and wide reading provides.

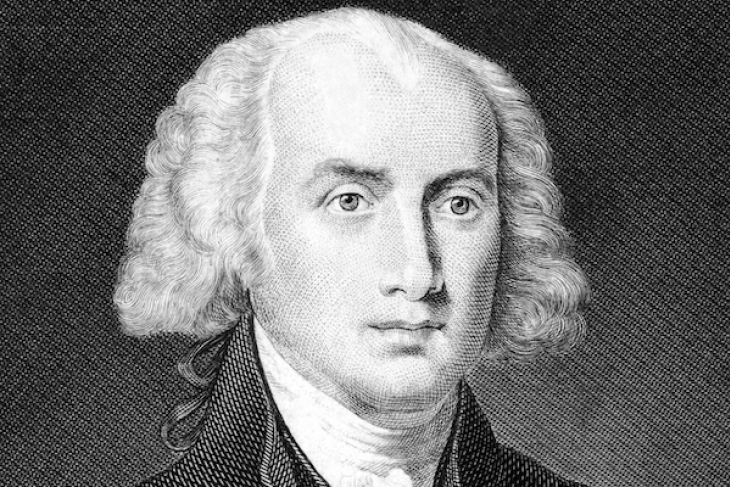

In an age when fewer Americans study foreign languages, there’s probably no point in wishing that children knew the word for “horse” in more than just their native tongue. Our students need less of Franklin’s wit and more of Madison’s wisdom. “Knowledge will forever govern ignorance,” he argued, “and a people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.” America loves proxies in education—multiple intelligences, focus on the whole child, metacognition. In the end, however, what counts is what is actually taught in actual classrooms, and how effectively children learn it. There should be no separation between the two: Enabling teachers to bring compelling, demanding content to their students is the healthy heartbeat of a good education.

1 Disclosure: As NYS Education Commissioner, I pushed for the funding that made the first edition of the EL Education curriculum available for free on line, and I serve on the Core Knowledge advisory board.