Almost every article on gifted education highlights inequity as an issue for the field. Indeed, inequity and large excellence gaps are among society’s most vexing educational problems, and scholars have proposed a variety of approaches to address them.

Universal screening and the use of local norms are prominent among these recommendations. Under local norms, gifted students don’t have to be in a high-performing school, they need to be high performing in their school. Local norms have been controversial, with critics arguing—often in the absence of solid evidence—that moving to local norms may not appreciably advance the cause of equity in gifted program participation rates. But a recent study we authored in AERA Open found that local norms do matter, and they matter a lot!

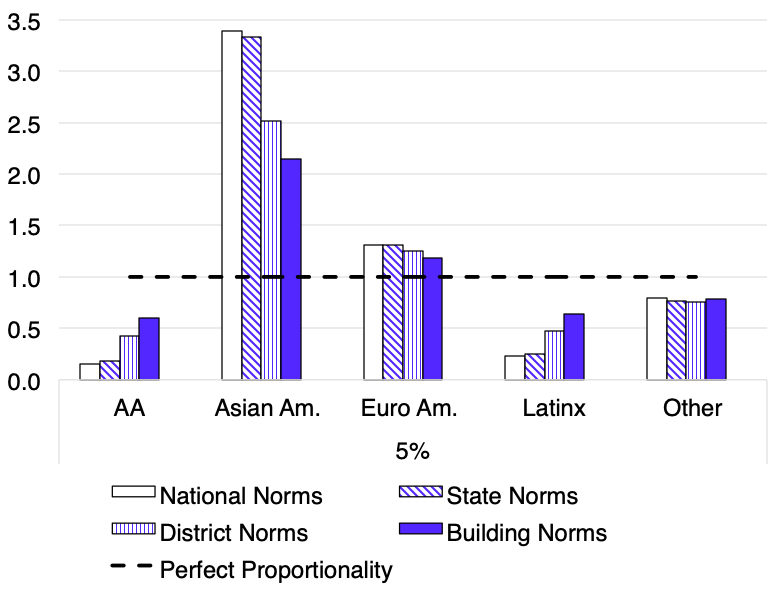

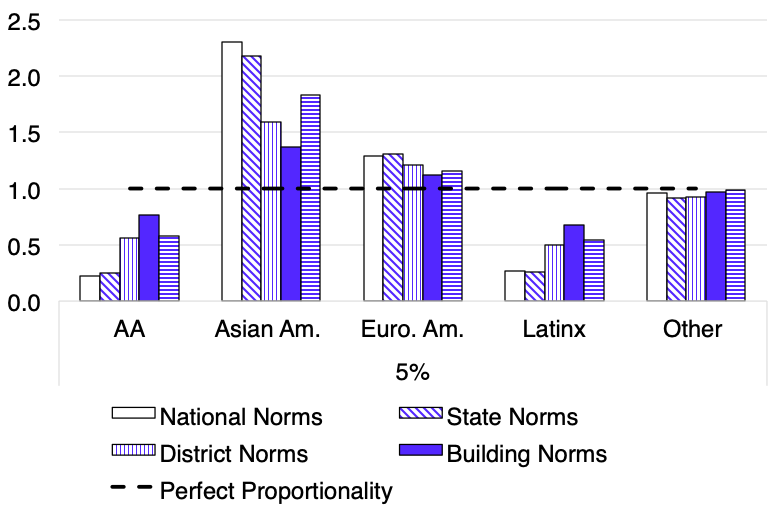

Local norms find advanced students hidden in plain sight. The purpose of our study, which used data from a ten-year period and from ten states, was to investigate the degree to which using different norms (national, state, district, or building) would influence racial and ethnic representation rates in gifted education. For context, a representation index (RI) of 1.0 translates to perfect proportionality of a group in the population identified as gifted.

We found that using building-level local norms would dramatically increase racial and ethnic equity in gifted programs. For example, as shown in the following figures, when the criteria for gifted is set at the top 5 percent of a school instead of the top 5 percent of the nation, we observed a 300 percent and 170 percent increase in African American and Hispanic student representation, respectively, in math. In reading, these increases were 238 and 157 percent, respectively. Although these students were still underrepresented, building norms resulted in a large increase in the number of them identified as gifted.

Some have correctly pointed out that using building-level norms could result in similarly-dramatic decreases in Asian American and European American identification rates under building norms (see the New York City specialized high school controversy). In fact, our study found evidence that this concern is well-founded (although we note students from these groups would still be disproportionally well represented). If the concern persists, there are other options, such as identifying students based on national or building norms, that moderate changes in representation. Of course, expanding services addresses this problem; in other words, rather than divvy the same pie of services up differently, creating winners and losers, create a bigger pie of services, creating only winners.

Figure 1. Representation indices (RI) by race and norm group in math, top 5 percent

Figure 2. Representation indices (RI) by race and norm group in reading, top 5 percent

An immediate challenge is that not every building has services to provide even if they all implemented local norms tomorrow. According to a new study published in Gifted Child Quarterly that used data from the Office of Civil Rights, over 42 percent of U.S. schools have zero students identified as gifted. This points to a major implication of what we propose: All schools would need to proactively plan for how they would challenge their most advanced learners. When educators examine performance relative to peers’ performance within each individual school building, gifted identification is about determining which children are not being challenged by the existing “grade level” instruction provided in a specific school setting. Every building has kids who could do more, and every building needs to proactively identify and serve those kids.

Local norm comparisons also are consistent with the definition of giftedness first advanced in the influential U.S. Department of Education “National Excellence” report, which recommended identifying student abilities only in comparison “with others of their age, experience, or environment.” Today, many schools draw their students from local neighborhood attendance zones that commonly are segregated by income, race, and ethnicity. This is why local norms work. By identifying talent in every building, gifted populations get closer to mirroring the larger student population.

Local norms are not a panacea, and they don’t result in perfect proportionality. But our analyses demonstrate that they represent a tremendous leap in the direction of better equity. Additionally, they are relatively easy to implement and carry almost no additional cost to students or schools. Local building-level norms are an early stage in the race to equity; they are not the finish line. Their use is an effective strategy for getting a more diverse student body served by the kinds of challenging programming and learning opportunities that will enable them to perform to their potential. Although there may be other strategies to help achieve greater equity in gifted identification and participation rates, we can’t imagine any that offer the same immediate impact as the local norms approach.

Scott Peters is Professor of Educational Foundations at University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, Karen Rambo-Hernandez is Associate Professor of Educational Psychology at West Virginia University, Matthew Makel is the Director of Research at the Duke University Talent Identification Program, Michael Matthews is Professor of Education at the University of North Carolina-Charlotte, and Jonathan Plucker is the Julian C. Stanley Professor of Talent Development at Johns Hopkins University.