A remarkable long-term study by University of Virginia researchers led by David Grissmer demonstrates unusually robust and beneficial effects on reading achievement among students in schools that teach E.D. Hirsch’s Core Knowledge sequence. The working paper offers compelling evidence to support what many of us have long believed: Hirsch has been right all along about what it takes to build reading comprehension. And we might be further along in raising reading achievement, closing achievement gaps, and broadly improving education outcomes if we’d been listening to him for the last few decades.

I’ve described countless times how teaching fifth grade in a low-scoring New York City public school made me a Hirsch disciple and a Core Knowledge enthusiast. Hirsch’s work—and only Hirsch’s work—described uncannily what I saw every day in my South Bronx classroom: children who could decode written text but struggled with reading comprehension.

My school’s staff developers, district consultants and coaches, ed school professors, and the literacy gurus they assigned us to read and study had different explanations for students’ reading struggles: Children were bored by required texts that didn’t reflect their interests and personal experiences. If we let them read what they wished, it would be more pleasurable and they’d spend more time at it. Classroom instruction was built around an all-purpose suite of reading “skills and strategies” that students could apply to any book. We were to “teach the child not the lesson,” make them fall in love with books and develop a “lifelong love of reading.” When students who appeared to be successful under this “child-centered” vision of literacy struggled on standardized tests, there was an answer for that, too: test anxiety and “inauthentic” assessments.

For more than four decades, Hirsch has responded to all this with a simple, cognitively unimpeachable, hiding-in-plain sight rejoinder: No, it’s background knowledge. Sophisticated language is a kind of shorthand resting on a body of common knowledge, cultural references, allusions, idioms, and context broadly shared among the literate. Writers and speakers make assumptions about what readers and listeners know. When those assumptions are correct, when everyone is operating with the same store of background knowledge, language comprehension seems fluid and effortless. When they are incorrect, confusion quickly creeps in until all meaning is lost. If we want every child to be literate and to participate fully in American life, we must ensure all have access to the broad body of knowledge that the literate take for granted.

The effects of knowledge on reading comprehension are well understood and easily demonstrated. The oft-cited “baseball study” performed by Donna Recht and Lauren Leslie showed that “poor” readers (based on standardized tests) handily outperform “good” readers when the ostensibly weak readers have prior knowledge about a topic (baseball) that the high-fliers lack. We also know that general knowledge correlates with general reading comprehension. University of Virginia cognitive scientist Dan Willingham, a co-author of the study, put it best in a video he made years ago: Teaching content is teaching reading. What has been more difficult to prove is that a specific curricular intervention aimed at systematically building students’ background knowledge can raise reading achievement. What the new study suggests is that not only is Hirsch’s theory solid, so is his prescription.

The six-year randomized control trial followed over 2,300 students who applied for kindergarten to one of nine oversubscribed Core Knowledge charter schools in the Denver area. Nearly 700 students who won seats in the lottery were compared to students who applied but ended up matriculating elsewhere. Researchers looked at state test results from third through sixth grade. The cumulative long-term gain from kindergarten to sixth grade for the Core Knowledge students was approximately 16 percentile points. Grissmer and his co-authors put this into sharp relief by noting that if we could collectively raise the reading scores of America’s fourth graders by the same amount as the Core Knowledge students in the study, the U.S. would rank among the top five countries on earth in reading achievement. At the one low-income school in the study, the gains were large enough to eliminate altogether the achievement gap associated with income. Eliminate it.

What’s critical to note about the study is that the effects of Core Knowledge are revealed slowly, over time, exactly as Hirsch’s theory predicts. He frequently observes that language comprehension is a slow-growing plant. One of the reasons for the dominance of bland, bloodless skills-and-strategies reading instruction is surely the idea that it can be employed immediately and on any text like a literacy Swiss Army Knife. But we must see language proficiency for what it is, not what we wish it to be: Reading comprehension is not a transferable skill that can be learned, practiced, and mastered in the absence of “domain” or topic knowledge. You must know at least a little about the subject you’re reading about to make sense of it. There are no shortcuts or quick fixes.

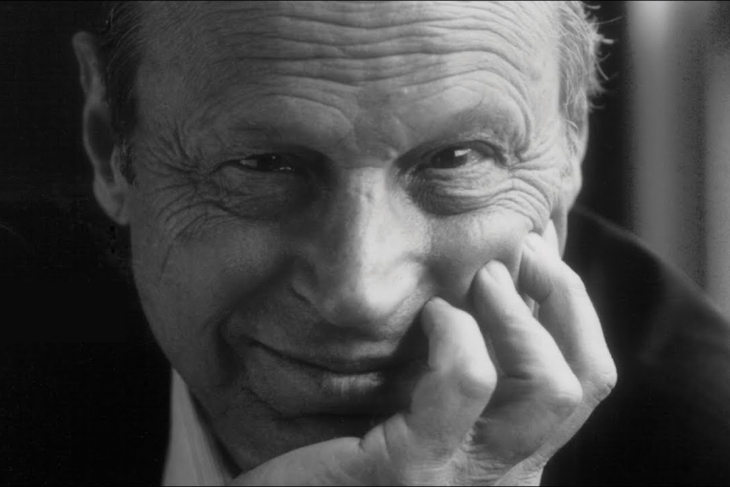

I called Don (the “D” in E.D. stands for Donald) earlier this week expecting him to be reveling in the study’s findings. He was indeed gratified. But having just turned 95 and congenitally modest, he’s not one for victory laps. Moreover, he’s American education’s Sisyphus, having pushed this rock up the hill many times only to see it roll back down as we get distracted by each shiny new thing. We talked for half an hour about the study, and how its outcomes might be even more powerful and replicable now that the Core Knowledge sequence has been codified in a language arts curriculum that hadn’t even been published when the researchers began following the Denver cohort. We talked about the power of literate culture to unite disparate people, the damage done to disadvantaged children when American education embraced progressive education ideas, and how misguided notions of social justice that make us reluctant to be prescriptive about what children should know end up imposing a kind of illiteracy on those we think we’re championing.

No single study is definitive, and even if it were, changing classroom practice is hard and faces stubborn resistance, particularly if the evidence shows things we would rather it didn’t. Hirsch has long had to face knee-jerk charges of Eurocentrism or worse, and that his object is to force-feed children a dead white-male curriculum and canon. It’s simply not so. Language—any language—bears the weight of its origins, which evolve over time, but cannot be stripped away. Not for nothing was Hirsch’s landmark work titled Cultural Literacy. The standard anti-Hirsch critique has always misunderstood entirely what his Core Knowledge project is about: It’s not an exercise in canon-making at all, but a curatorial effort, an earnest attempt to catalog the background knowledge that literate Americans know so as to democratize it, offering it to those least likely to gain access to it in their homes and daily lives. We are powerless to impose our will on spoken and written English and to make it conform to our tastes. Our only practical option is to teach it.

There has never been a fairer, more equitable, and frankly progressive effort to ensure that our least fortunate students have access to the same knowledge that affluent Americans seem to absorb through their pores. Hirsch’s work offers knowledge have-nots the language of power. That some might seek to deny access to it has long seemed to me among the greatest and most unforgivable of educational crimes. And now there’s a powerful proof point that makes continuing in that obstruction even less forgivable than it was yesterday.

I’ve said for years that if you’re not serious about literacy, you’re not serious about equity. I’ll go one step further: If you’re not serious about Hirsch, you’re not serious about literacy, or about equity.