“They already made up in their mind that they’re not going to give [my children] back. I feel as though they want me to say, ‘F**k it, let me just sign, take ’em.’ I get to that point. I get there. That’s why I’ve been late. I can be on time. But when I’m at home getting ready, I don’t see an end to this tunnel, I don’t see a light, it’s just pitch black. This is a frickin’ routine that is never going to f**king end, and I feel like I’m drowning all the time. Lord knows I love my kids. But at the end of the day, it’s only so much one person is willing to take.”

—Mercedes, single mother of four children

In the grueling world of education reform, we are inundated with mind-numbing statistics about the generational academic failure suffered by millions of students, many of whom are “of color or living in poverty.” Yet rarely do we have the opportunity to go beyond these nameless, faceless identity groupings of race and class to understand the human story of the individual souls in our classrooms. Rarer still is empathy for the circumstances of the adult caregivers of the students we serve, who despite their own life tragedies are seeking better outcomes for their children.

One such story is that of Mercedes and her four children, Amaya, Camron, Leslie, and Tiana. Mercedes is twenty-five, has never been married, and has spent eight years fighting with the Bronx Family Court trying to gain and regain custody of Camron, Leslie, and Tiana. A recent New Yorker article titled “When Should a Child Be Taken from His Parents” chronicles Mercedes’s harrowing saga of homelessness and single parenthood, while she struggles to raise children who have their own mental health issues and special education needs. Given their boomeranging in and out of foster care, Mercedes provided pseudonyms for each child to protect their privacy and lessen the chances of another forced removal of her children from her home. The despair Mercedes expresses above is truly heartbreaking and highlights her frustration with a beleaguered child welfare system that overwhelms even the most well-intended professionals trying to protect the interests of traumatized children.

There is no way to absorb Mercedes’s story without acknowledging that the tragedy her life has become was partially caused by factors beyond her control: a drunk, physically-abusive father; even more violent relationships with men; entrenched poverty; and a host of systemic barriers. Yet simultaneously, Mercedes’s multiple non-marital births to different long-gone men, her drug addiction, and a series of other self-inflicted wounds means that her individual choices, and those of the men who abandoned her and their children, also make them partially responsible for the predicament she and her kids are suffering through.

There is lots of blame to go around.

Understanding the complexities of Mercedes’s life helps educators develop deep empathy for her, her children, and the students in our own classrooms, many of whom also struggle through the burden of family dysfunction. But with that empathy comes an equally important and urgent responsibility: Be brave. Have the courage to name what Mercedes’s story reveals, that structural barriers around race and poverty, as well as individual choices around family structure and timing of family formation, are causal factors that deeply damage the life prospects for her children.

The challenges that Amaya, Camron, Leslie, and Tiana will face are extraordinary, and were unfairly caused by conditions created by the adults in their lives. Unfortunately for them and millions of children like them, their adverse start in life is tragically ordinary.

***

“According to Census Bureau data, a two-parent black household is more likely to be poor than is a two-parent white household, but both are far less likely to be poor than is a mother-only household of either race. In other words, if you are a baby about to be born, your best odds are to choose married black parents over unmarried white ones.”

—Jonathan Rauch

In May 2001, when journalist Jonathan Rauch wrote these controversial words in The National Review, he was calling attention to the fact that, in economic terms, a parent’s marital status had displaced race and class as a primary driver of child poverty. His data proved that “the long-term presence of two parents—in other words, marriage—is a better predictor of a child's life chances than is race or income, and that illegitimacy and single parenthood are risky no matter what your race or income.”

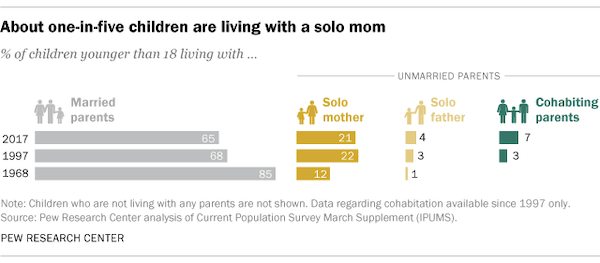

Nearly two decades later, the issue has only grown more acute as social mobility in America has declined. Indeed, in April 2018, the Pew Research Center reported that “the share of U.S. children living with an unmarried parent has more than doubled since 1968, jumping from 13 percent to 32 percent in 2017. That trend has been accompanied by a drop in the share of children living with two married parents, down from 85 percent in 1968 to 65 percent.”

Source: Gretchen Livingston, “About one-third of U.S. children are living with an unmarried parent,” Pew Research Center (April 27, 2018).

This trend is likely to continue, given the decline in marital childbearing among young men and women. Indeed, in each of the National Center for Health Statistics’s Final Birth Data Reports for 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, and 2013, it found that the non-marital birth rate to women of all races aged twenty-four and under held steady at an astronomical 71 percent for the last five years. Similarly, for each of the last five years, more than 41 percent of women who gave birth were already unmarried mothers at or under the age of twenty-four. And these already unwed, young mothers were giving birth to their second through eighth child.

In raw numbers, this means that in each of the last five years, unmarried young women who had given birth during that time are raising an estimated 1.1 million or more children. And what of the men? In “How Family Background Influences Student Achievement,” researcher Anna Egalite notes that, “In the case of nonmarital births, estimates say that 56 percent of fathers will be living away from their child by his or her third birthday.”

We probably all know stories of heroic, unmarried young parents who have defied the statistics and created a great future for their kids. But like Mercedes, who gave birth serially as an unmarried mother, this vulnerable population of young adult caregivers is much more likely than their less vulnerable peers to be undereducated, poor, and suffer mental health issues that lead to chronic stress and poor academic outcomes in their children.

Indeed, according to the Annie E. Casey Foundation, children of young unwed mothers will be nearly five times as likely to be raised in poverty, as compared to children raised in two-parent homes. And five decades ago, the landmark “Equality of Educational Opportunity” study, better known as the Coleman Report, established the primacy of family background versus in-school factors as far more determinative of student achievement outcomes.

For Mercedes’s children and the millions like them growing up in communities in which non-marital births are the norm, they need to learn the pathways that give them the best chance to break the hamster wheel of family instability and poverty for their own lives.

***

The challenge is that, when it comes to the topic of family structure, many education reformers seem to invoke Reinhold Niebuhr’s Serenity Prayer: “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; the courage to change the things I can; and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Educators typically resign themselves to assuming that improving the home environment of their students is in the domain of “things I cannot change.” In the parlance of Teach For America corps members, it is outside of their “locus of control.” But what matters is not what is in the locus of control of educators. What matters is that we teach each student about his or her own individual locus of control, and thus the personal decision-making power they have to control their own destiny.

In fact, there is a sequence of personal life decisions—completing at least a high school degree, working full-time, and marrying before bearing children—that gives low-income students of all races the greatest probability to enter the middle class or beyond. As Wendy Wang and Brad Wilcox found in their recent research, 94 percent of young adults from lower-income families manage to avoid poverty if they followed all three steps of this “Success Sequence.” How can we in good conscience deprive our students of this information about the different pathways into adulthood that have very different rewards and consequences? Shouldn’t we teach them about what they can do to have a better chance at success in life?

Indeed, philanthropists, policymakers, and education reformers would be wise to spur innovation and fund pilots for middle and high schools to teach data associated with the Success Sequence. Schools have the unique responsibility to empower their graduates to develop the personal agency over the forces they do control, and to give them the best shot to withstand the pressures of the forces they don't control, such as life's adversities and the effects of systemic racism, sexism, and poverty.

***

Regardless of the decisions Mercedes may have made in her own life, or those that were forced upon her, parents like her are counting on educators to ensure her children know the series of choices within their power that will likely lead them to realize their human potential.

Each day, Mercedes sends Amaya, Camron, Leslie, and Tiana to their local school, where they seek and deserve an education that will empower them to lead lives vastly different from their mother and respective fathers.

For our own serenity, I pray that we have the courage and the wisdom to know we can make that difference.