Last month, Alabama’s Governor Kay Ivey signed the Alabama Literacy Act into law, making the state the nineteenth to require third grade reading retention. It’s a policy with roots in California, but that got its legs in Florida under former Governor Jeb Bush. Freelance reporter Alexandra Starr recently reported on the subject for NPR’s “All Things Considered.” A follow up segment is also in the works.

Reading proficiently by the end of third grade is considered a significant milestone and gateway to lifelong success. A third grader who cannot read proficiently is four times less likely to graduate from high school than one who can. To encourage schools and districts to take this milestone seriously, states like Alabama have enacted legislation to hold back students who are not reading proficiently by the end of third grade. That said, states have approached this effort in a variety of ways. Some mandate retention, while others allow for retention but do not require it.

The research on retention is voluminous. Hundreds of studies have been carried out on the subject, most with a focus on the elementary level. At first blush, the “weight” of the evidence makes it tempting to argue that retention is ineffective, but that would be akin to printing out all of the studies, organizing them by those finding positive and negative effects, and then deeming the heavier pile the more credible—an exercise all too common with education research.

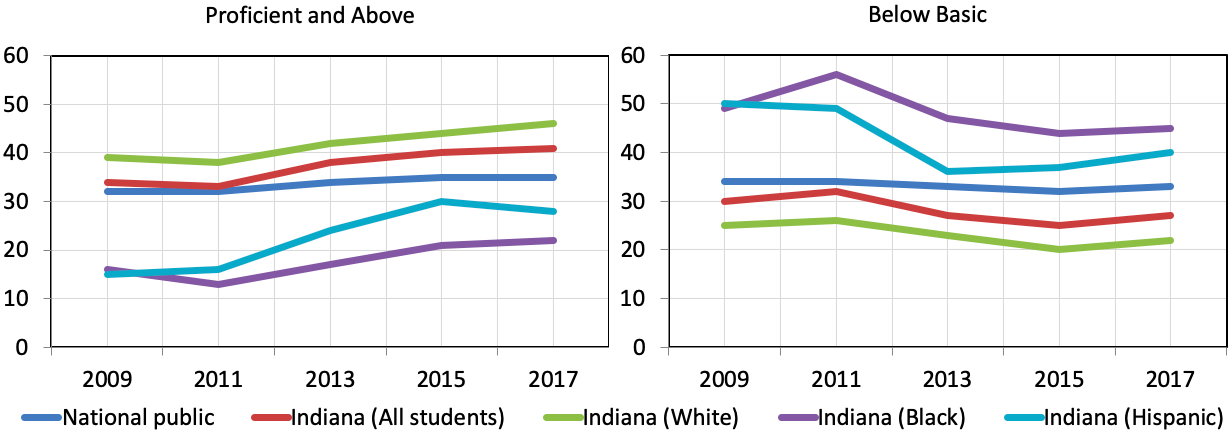

Though the matter is far from settled, an examination of newer Florida-type policies show that retention based on objective measures plus intensive interventions work. As an example, Indiana—where I worked as an assistant state superintendent—passed such a law in 2010. Since the state’s enactment of the policy, fourth grade reading has steadily improved. It’s difficult to draw causal inferences from NAEP, but as Figure 1 illustrates, Indiana increased the percentage of students proficient in reading while decreasing the percentage of students scoring below basic—a trend which held for all principal subgroups.

Figure 1. NAEP fourth grade reading scores, by percentage of all students at achievement levels, 2009–17

As is common in states that adopt retention mandates tied to third-grade reading, the initial reaction was one of resistance from Alabama’s education establishment, including the state’s department of education, school superintendents, principals, and school boards. We faced similar opposition in Indiana. Everyone shares the goal of improving reading in the early grades, but policymakers and practitioners tend to part ways on retention—which is frowned upon for a litany of reasons ranging from the cost of holding students back to the potential stigma and damage to students’ self-esteem. Yet the prevailing practice of social promotion has proven exponentially more destructive.

Furthermore, the question of how to test for reading proficiency, especially reading comprehension, is a complexifier in the retention debate. My colleague Robert Pondiscio has written extensively on the topic, and pointed out that reading tests in grades three through eight send instructionally troubling signals to teachers and can incentivize bad practice. The burgeoning trend of valorizing knowledge acquisition is an indubitably positive one, but removing reading tests altogether strikes me as a bridge too far.

To wit, it seems to me that the arguments against reading tests or retention are allowing the perfect to be the enemy of the good. The effects of retention on academic achievement may be a mixed bag, but eight states with comprehensive reading policies have made greater gains than those without. And it’s unclear what long-term impacts retention may have on metrics like college enrollment or average earnings. Hopefully, it’s a question that will be answered by future research. In the meantime, there’s a lot to be said about the accountability provided when a state’s framework includes retention in the toolkit.

The naysayers will argue that, by retaining low-achieving third graders and providing them an extra year in school, states like Florida were able to artificially boost their numbers on federally required tests in fourth grade. This claim has always been part of the retention debate, though its veracity is questionable, with one recent study showing that the extra year does not explain the difference in student performance.

This is one of many such misconceptions of mandatory retention policies, but they are not as draconian as they are often reported to be. Most include good-cause exemptions—such as for special education students and those with limited English proficiency—that provide local leaders considerable latitude in adhering to the law. In Florida, fewer than half of students not meeting the promotion standard on the state test are actually retained. Moreover, these laws consider retention a “last-resort” measure. On its own, retention would service little purpose if there were no change in approach or practice the following year. An effective policy must include retention alongside early identification, teacher training, intensive reading intervention, and parent involvement.

It’s taken twenty years, but more states are rightfully giving social promotion the third degree. And thanks to the post-recession “Baby Bust,” it’s happening at the most opportune time. Reading instruction still leaves much to be desired, but it’s doubtful the states that really need to focus on the issue would do so without the encouragement provided by a statutory requirement. Case in point: The effects of Indiana’s third grade reading statute are now part of the state’s DNA. As one Hoosier official recently concluded, “Without legislation, I don’t know if the focus would be on literacy. All eyes are on all children reading by the end of third grade.”