Summer ’19 is showing its age: My daughter recently returned to school, bright yellow buses are canvassing my neighborhood again, and Pumpkin Spice Latte is back. Education reform’s momentum is also ebbing with news from Newark that the city’s new teachers’ contract scraps performance-based pay and reinstitutes a step-and-lane model based on experience and credentials. (As if lead in the water weren’t trouble enough!)

How far things have veered off course. Back in 2012, Newark was lauded for a groundbreaking contract that took aim at the stubborn widget effect. Since then, of course, merit pay has been a flashpoint in Newark and nationally. In 2011, I helped to abolish salary schedules in Indiana; now establishment forces have proposed bringing them back. In the District of Columbia, the archetype of performance pay systems is currently under siege. Here in Denver, the February teachers strike effectively gutted the district’s once-promising and much admired pay system.

Never mind the positive results in each of these locations. Or recent research suggesting that forward-thinking pay systems can—contrary to popular perception—help improve student performance. Skepticism persists in spite of the obvious cost effectiveness of this reform versus such interventions as class size reduction. Still, fears of merit pay’s negative side effects (e.g., dampened morale, reduced collaboration) are widespread—spread, of course, by teacher unions and their friends—and the myth building around it has occurred at an alarming rate.

AEI’s Rick Hess has written extensively on this topic and notes that debates around merit pay often fail to address the questions that really matter. Rather than asking how teacher pay might help us reshape the profession and make it more attractive to talented candidates, the discourse is weighted down by broad assertions that performance-based pay doesn’t work. Hess observes:

As school systems wrestle with tough fiscal decisions, it's vital to understand that one-size-fits-all pay is insensitive to questions of productivity. Although the term "productivity" is typically regarded as a four-letter word in K-12 conversations, teacher productivity means nothing more than how much good a given teacher can do. If one teacher is regarded by colleagues as a far more valued mentor than another, or helps students master skills much more rapidly than another, it's axiomatic that one teacher is more productive than the other. Yet, step-and-lane pay makes no allowance for such differences.

It’s true that measuring teacher productivity is easier said than done, partly because—just about everyone now agrees—it shouldn’t be limited to test scores. Yet the challenge is surmountable if we seriously commit to untangling the web of interrelated issues at play. Specifically, the need to (1) improve teacher compensation, (2) rethink the profession in a manner that attracts great candidates and elevates great teaching, and (3) modernize expensive and unsustainable pension systems.

Hess believes that doing so requires common sense, compromise, and shared sacrifice—qualities that were scarce around the bargaining table in Newark. Indeed, the new agreement shifts from a pay structure that endeavored to reward good teaching to one that blatantly ignores performance. The fact that 96 percent of highly effective teachers were choosing to stay in the district and 49 percent of ineffective ones were voluntarily leaving had no evident bearing on the negotiations. The deal casts aside bonuses for top-rated teachers and replaces them with bonuses for longevity. It’s hard to see how such a move squares with the union’s constant call for teachers to be treated more like professionals.

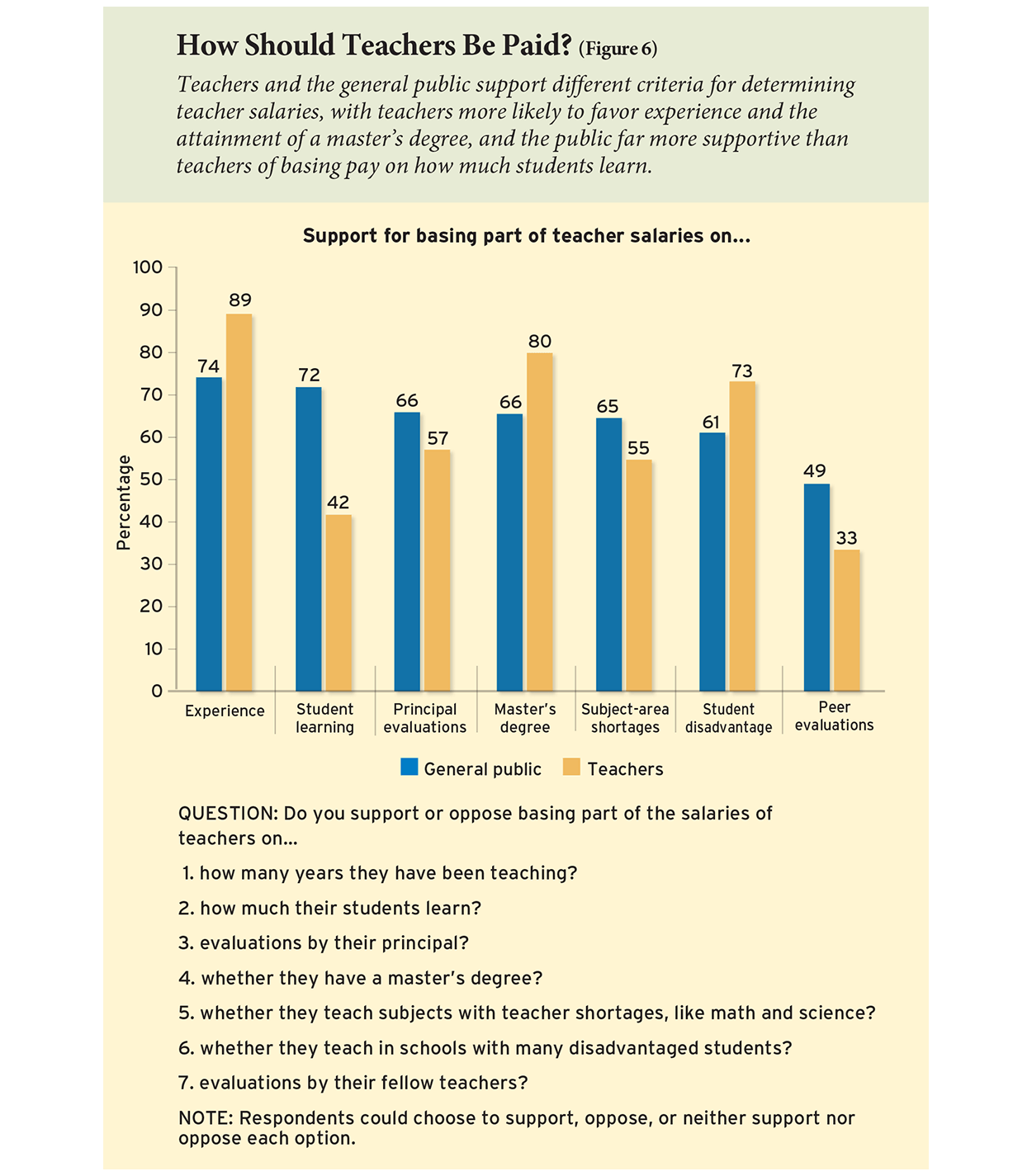

The latest Education Next survey is instructive. Though pollsters found that 72 percent of respondents favor raises for teachers, the public doesn’t see eye to eye with teachers on the factors that should determine their compensation. Nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of teachers are against merit pay, and even larger majorities favor the traditional determinants of pay, like experience (89 percent) and master’s degrees (80 percent). The general public supports those factors, too, but not nearly as strongly. Most notably, as shown in the figure below, two in five teachers (42 percent) support the use of student learning as a salary determinant while nearly three-quarters of the public (72 percent) does.

Jettisoning merit pay in Newark is thus consistent with the sentiment of teachers more broadly, but it’s at cross-purposes with what parents and voters desire. Given the tumult with performance bonuses and incentives, I can understand and sympathize with the dissatisfaction among teachers, but this rancor could be put to better use in service of improving these systems rather than retreating to a status quo that the literature has repeatedly shown to be ineffective.

Newark’s U-turn is a cautionary tale—one with multiple storylines, including the persistence and perseverance of entrenched interest groups. Newark is also the latest example of why attempts to turn around low-performing schools and districts have proven so difficult. Funders might seriously consider pressing pause on efforts to fix urban districts and direct their energies instead towards replacing them.

If only. Minus an act of God, shuttering districts is harder than moving a cemetery. Major reforms of those districts are almost as demanding. And the prevailing mood—not just in Newark—prefers reflexive cash drops to the discomfort, ingenuity, and persistence needed to both strategically raise salaries and address pension shortfalls. The window of opportunity here appears to be closing if it’s not already shut.