Editor’s note: This is an edition of “Advance,” a newsletter from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute written by Brandon Wright, our Editorial Director, and published every other week. Its purpose is to monitor the progress of gifted education in America, including legal and legislative developments, policy and leadership changes, emerging research, grassroots efforts, and more. You can subscribe on the Fordham Institute website and the newsletter’s Substack.

Last week, the U.S. Department of Education released the latest batch of alarming national test results for America’s students—this time, long-term-trend data for thirteen-year-olds in reading and math. This builds on three other releases since 2022: long-term-trend data for nine-year-olds, scores for fourth and eighth graders, and civics and U.S. History results for eighth graders.

The nation is, at this point, well aware of the problem: Students everywhere suffered learning losses during the pandemic, especially those from marginalized backgrounds. As I’ve written multiple times, this is true for advanced learners, too—the subset of students who have reached, or have the potential to reach, the high end of the achievement spectrum—who are also the students on which this newsletter focuses. The latest batch of scores for thirteen-year-olds supports all of this.

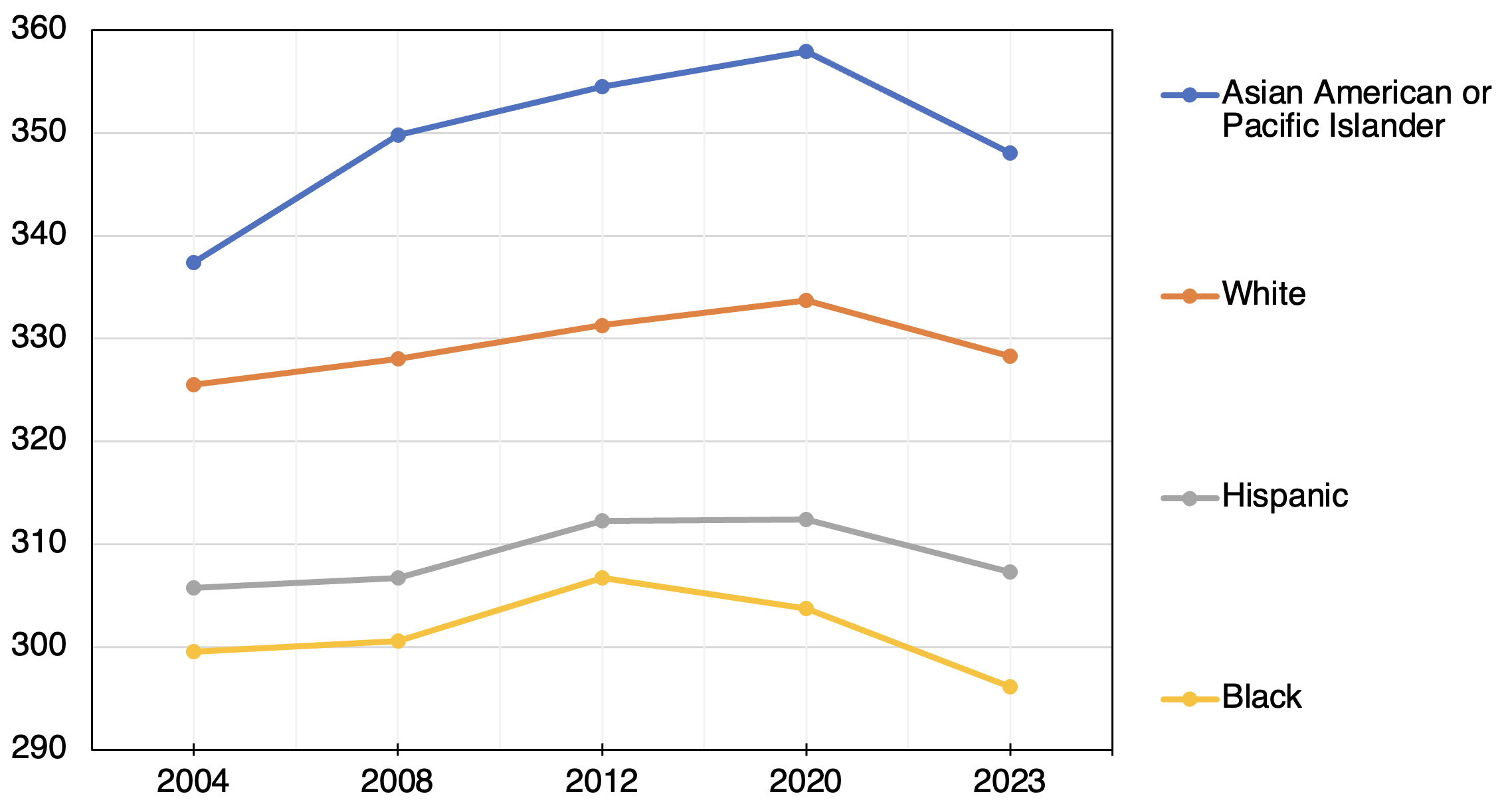

Consider, for example, the results for math—where “proficiency in eighth grade is one of the most significant predictors of success in high school,” according to a Wall Street Journal report last year. Figure 1 shows 90th percentile marks by race and ethnicity.

Figure 1. NAEP long-term trend mathematics assessment, 90th percentile scores, by race and ethnicity, 2004–23

At least three takeaways are noteworthy. First, of course, are the huge gaps in performance between groups, with the 90th percentile scores for Black and Hispanic students being far below those for White and Asian or Pacific Islander (AAPI) students. Second, those gaps have grown since 2004, with the Black-AAPI difference going from 37 points to 52 points, for example, and the Black-White gap widening from 26 to 32 points. Third, top scores dropped significantly for all the groups after the pandemic, with those for AAPI, White, and Hispanic students falling back to where they were approximately fifteen years ago—and those for Black students plummeting well below where they were twenty years ago.

But again, none of this is new or surprising. It’s just tragic and worrisome. The challenge now is doing something about it—finding ways to reverse these losses and get students closer to where they would’ve been had Covid and related mitigation policies not decimated learning.

For advanced learners, an excellent place for districts, charter networks, and states to start is a report released this month by The National Working Group on Advanced Education—a collection of twenty researchers, practitioners, and advocates (including myself), who are diverse in terms of ideology, race, gender, and geography. We met four times over the past year, and the report is the product of that work. It comprises thirty-six recommendations for how K–12 leaders can build a continuum of advanced learning opportunities, customized to every student’s needs and abilities—especially for those from marginalized backgrounds.

Leaders would be wise to follow all thirty-six recommendations, but those that fall into two categories are particularly relevant in the context of pandemic learning loss: identification and equitable achievement grouping.

As we write in the report, schools shouldn’t think of identifying advanced learners as a “yes or no,” one-time event. The goal is to keep seeking—and finding—all students who could benefit from advanced learning, whatever the subject and whatever their grade level, all the way up to dual-enrollment in a university. This is especially true now that scores for high achievers are lower than they were before the pandemic. Schools should therefore adopt a bias toward inclusion.

Specifically, districts and charter networks should do the following (also from the report):

- Adopt universal screening to identify students with potential for high achievement. Such screening involves reviewing assessment data and/or grades for all students to identify those who might benefit from advanced learning opportunities. This has strong empirical support and leads to positive results in districts that have used it. It helps identify more students overall, and it’s especially beneficial for the students most often overlooked for advanced learning opportunities.

- Use data from universally available assessments. Multiple tests or data points are better than one because some students will shine on one assessment and not another. For example, tests that measure general ability and don’t require academic knowledge will help identify students who have the potential to perform at advanced levels of achievement but don’t yet have strong content knowledge. Nonverbal assessments can help identify students whose learning hasn’t caught up with their high potential due to language or cultural barriers.

If diagnostic or interim assessments are used universally in the early grades (K–2), districts and networks should use them as initial screeners, but at the latest they should start with third-grade statewide reading and math assessments (officials should be sure to age adjust the results so as not to miss students with late birthdays). - Use assessment data to identify additional students for advanced education services in every grade, instead of relying on a single age-based screening point that would overlook late bloomers and/or exacerbate racial or socioeconomic disparities.

- Use local (i.e., school-based) norms, especially when students are young. This means identifying and serving high-potential students in every school (for example, students whose achievement levels are in the top 10 percent in each school). As students move into high school, it may be appropriate to reference state or national norms when admitting students to advanced programs so that students are better prepared to compete in higher education and beyond. Thankfully, research shows that providing access to advanced education in elementary school can help to close equity gaps and broaden participation in advanced coursework in later grades.

Once students are identified, one the best and most popular ways to develop their potential is through flexible achievement grouping in the same or separate classrooms. Numerous high-quality studies have also found that this is a net positive for advanced students and isn’t detrimental to their peers. One study that looked at a century of research, for example, found that three models boosted outcomes: within-class grouping, cross-grade subject grouping, and special grouping for the gifted. Moreover, there seemed to be little downside for medium- and low-achieving students, and often upside.

Specifically, as we note in the report, districts and charter networks should do the following:

- Frequently and equitably evaluate all students with the purpose of moving them into appropriate achievement groups. This is not “one-and-done” tracking. Putting students in buckets that never change is ineffective, inequitable, and counter to what we know about development. Rather, schools should use data from multiple measures—such as test scores and class performance—to continually assess and move students, regularly regrouping them with multiple entry points (“on-ramps”). District and school leaders should be prepared to provide teachers with support where necessary to achieve this.

- Ensure that teachers alter the complexity and pace of the curriculum, as well as methods of teaching, when using achievement groups. Grouping is only as equitable and effective as the differentiated and culturally responsive instruction that is aligned to the needs of a given group.

- Err on the side of inclusion, so that as many students can benefit as possible. The question should be whether a student has a need or would benefit from a particular service. When this isn’t clear, schools should err on the side of giving students access to a more advanced group with intentional support. All of this avoids the problem of artificial and arbitrary scarcity.

The current state of American education is bad, and advanced learners are no exception. Policymakers and school leaders will be tempted to ignore losses at the high end, but they’d be doing so at the country’s peril. We need advanced learners, particularly students from racially underrepresented or low-income backgrounds, to be highly educated to ensure the nation’s long-term competitiveness, security, and innovation. Making these programs accessible also strengthens our society and democracy. These students and their learning therefore need to be part of the recovery effort. The recommendations listed here—and in the aforementioned report—are an effective guide.

—

QUOTE OF NOTE

“A math academy for young Black boys this summer aims to not only help the young men prepare for advanced math classes but close the widening achievement gap between the races in local schools. M-Cubed, which stands for ‘Math, Men, and Mission,’ is dedicated to help middle school students from Charlottesville and Albemarle County achieve higher math class placements once they reach high school.”

—Faith Redd, The Daily Progress, June 21, 2023

—

RESEARCH REVIEW

“Gifted and On the Move: The Impact of Losing the Gifted Label for Military Connected Students,” by Robyn Hilt, Journal for the Education of the Gifted, OnlineFirst, June 2, 2023

“Society is becoming increasingly mobile, which impacts all facets of the educational experience, including gifted education. Military students attend several different schools in their educational careers, and inconsistent criteria and identification practices among states and school districts result in a fluid gifted label for many of these students. While some aspects of school mobility are highlighted in existing research, limited attention has been paid to school mobility within gifted education. This research works to address this gap by exploring the impact of losing the gifted label on children of military members, whose relocations frequently require mobility across state and district boundaries, utilizing a unique framework, Foucault’s technologies of self. Research findings explore student perspectives on the impact of their own effort or hard work on their ability to retain the gifted label and serve as a launching point from which to explore the issue of school mobility in gifted education.”

“Development of an Online, Culturally Responsive, Accelerated Language Arts Curriculum for Middle School Students,” by Jennifer H. Robins, Laila Y. Sanguras, and Ashley Y. Carpenter, Gifted Child Today, Volume 46, Issue 3, June 2023

“In this article, we focus on two components of the Online Curriculum Consortium for Accelerating Middle School (OCCAMS) project: the curriculum frameworks and the curriculum development process. The frameworks include the Integrated Curriculum Model (advanced content, unit themes, and process/product), culturally responsive curriculum, and talent development. In our discussion of the curriculum frameworks, we share how two accelerated, online courses centered on themes that motivate and engage diverse learners: identity, heroism, conviction, and sacrifice. In addition, we highlight how the exploration of these themes through texts written by diverse authors and featuring diverse characters allows students to go on an even deeper journey into self-discovery. The second focus of this article is on the curriculum development process. We illustrate the iterative nature of the development of the curriculum, including descriptions of the site visits and use of teacher and student feedback in each stage of revisions.”

“Educational Technology: Barrier or Bridge to Equitable Access to Advanced Learning Opportunities?” by Sarah Bright and Eric Calvert Gifted Child Today, Volume 46, Issue 3, June 2023

“Using a critical technology theoretical framework that examines the impact of technology on people at the individual, educational, and global levels and addresses questions around appropriate use, accessibility, and impact, [Project OCCAMS] outcomes are explored through an interpretive focus on equity, including impacts on student achievement as well as students’ subjective experiences in the program. Potential implications for broader efforts in the field of gifted education to reduce disproportionality in gifted identification and close opportunity and excellence gaps beyond gifted identification reforms are also explored.”

—

WRITING WORTH READING

“[Lamar Institute of Technology, Beaumont, Texas,] expanding its presence through dual credit partnerships,” Beaumont Enterprise, Olivia Malick, June 25, 2023

“Progressive backlash? A coalition pressing for more selectivity in schools notches key wins in NYC education council elections,” New York Daily News, Cayla Bamberger, June 24, 2023

“Summer math academy aimed at preparing Black students, closing achievement gap,” The Daily Progress, Faith Redd, June 21, 2023

“Darien [Connecticut] DEI report finds literacy disparities and lack of diversity in gifted program, special education,” The Darien Times, Mollie Hersh, June 20, 2023

“College-level exam results among Long Island high schoolers show improvement,” Newsday, John Hildebrand, June 19, 2023

“What do gifted children need? Future Scientists Center offers answers,” The Jerusalem Press, June 19, 2023

“19-year-old UC Davis grad one of youngest people in the world to earn Ph.D.” KCRA, Hilda Flores, June 19, 2023

“World science scholars hosts science festival for gifted students from 6 continents,” World Science Scholars, June 15, 2023

“12-year-old graduated from college with a 4.0 GPA—here’s why her parents are sending her to high school,” CNBC, Rebecca Picciotto, June 15, 2023

“14-year-old Pleasanton whiz graduates Santa Clara University, gets job at SpaceX,” KTVU, June 12, 2023