Editor’s note: This essay is an entry in Fordham’s 2021 Wonkathon, which asked contributors to address a fundamental and challenging question: “How can schools best address students’ mental health needs coming out of the Covid-19 pandemic without shortchanging academic instruction?” Click here to learn more.

Psychologists agree that social disruption and instability can lead to neurological changes that can have lasting impacts in the brain and consequently behavior. A little over a year ago, around March 2020, as the coronavirus spread around the world, governments were forced to quickly develop ways to try to mitigate the exasperatingly fast rate of infection and death from Covid-19. In the United States, the public was ordered to stay home, there were quarantine mandates for those who had contracted, or had been exposed to, the virus, and the wearing of face masks became a must. The combination of the sudden arrival of this deadly pandemic, the likes of which the world had not seen since the Spanish Influenza of 1918, and its abrupt disruption to our lives through infections, or the fear of it, and deaths created what we are all still dealing with today. To put this in some perspective, consider the fact that the first case of coronavirus in the U.S. was reported on January 21, 2020 and as of May 10, 2021, 32,707,750 people have been infected and 581,516 individuals have died as a result of this pandemic.

The hallmarks of the pandemic on the mental health of the population include extreme stress, loneliness, isolation, depression, and anxiety. Thankfully, the advent of the Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and Johnson and Johnson/Janssen vaccines have made the thought of resumption to “normal” life somewhat of a reality and schools and school districts are now planning full-scale in-person learning. However, since we know that there is a very high likelihood that students’ mental health has been heavily impacted due to this pandemic, it makes sense for schools to begin planning targeted intervention approaches to identifying, treating, and supporting the potential treat to learning and well-being that can occur as a result. Why? Because emotional distress, regardless of how it is acquired, constitutes a significant barrier to learning that must be ameliorated, if not completely removed, for learning to happen. This is more so with the Covid-19 pandemic and academic instruction.

As an important first step to addressing students’ mental health needs as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, schools must proactively recognize that this enormous challenge exists and advise students and their families that they are not alone in confronting these challenges. This means that schools must be equipped to identify the early signs of distress in students: increased levels of stress, unexplained apprehension, indifference, sudden and/or extreme mood swings, and refusing to participate in activities in which they would otherwise have no problems participating. Within the school building, everyone should be encouraged to look out for each other to identify these signs because students are not the only ones at risk, although their mental needs should be prioritized as they are more vulnerable and less equipped to deal with the types of upheavals brought on by Covid-19. Proactive recognition and identification of the early warning signs of students’ mental health needs will require training, therefore schools should provide additional adequate training for all staff members in relation to this. Ideally this should be happening now with plans for continued reinforcement and modification throughout the upcoming school year and beyond.

The scope of this issue may require schools to hire and train additional guidance counselors (GC), school psychologists, and social workers to provide needed timely interventions in the form of regular case conferencing for the more serious scenarios. This means substantial additional funding from the government to cover the cost of hiring and training these professionals so that they can perform their obligations effectively. Thankfully, on March 21, 2021, the Biden Administration signed into law the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARP), also called the COVID-19 Stimulus Package or the American Rescue Plan, providing $1.9 trillion economic stimulus to accelerate economic and health-related recovery from the excruciatingly damaging effects of Covid-19. This is in addition to the $2.2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, also known as the CARES Act from March 2020 and the $2.3 trillion Consolidated Appropriations Act of December 21, 2020. There is indisputably a lot of money to begin the process of addressing students’ mental health needs emanating from the Covid-19 pandemic without shortchanging instruction. However, although funding availability is a necessary condition for tackling these issues, it is not a sufficient condition for planning and executing effective solutions to meet the real-life of students without shortchanging instruction.

Getting students back to school for in-person learning and drastically limiting remote schooling to those extreme circumstances where it is absolutely and medically necessary is critically important. Strongly encouraging everyone to get vaccinated is equally important for a safe in-person reopening. Getting the vaccine should not mean abandoning the erstwhile precautions of face coverings and social distance. Schools should partner with local hospitals and/or clinics to facilitate vaccinations for staff and students. In schools where there are clinics on the premises, efforts should be directed to making the vaccine available in these clinics. Being vaccinated can provide a level of security that positively impacts mental health as well as expedite returning to school and thus ending isolation.

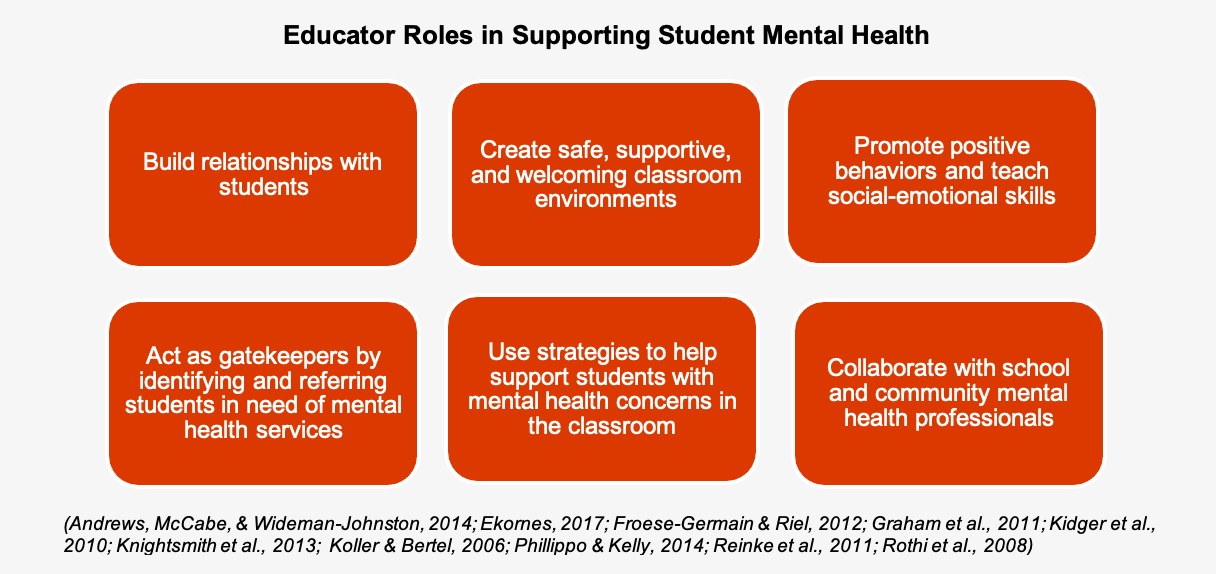

In addition to being able to quickly identify students who might be predisposed to Covid-19 related emotional distress, the American Psychological Association (APA) suggests “a systematic screening of the school population” involving the completion of questionnaires by teachers and/or students pertaining to emotions and classroom behaviors (elementary schools) and frequency or severity of any emotional concerns (middle and high schools). The results of these questionnaires are then used to gauge/screen students’ emotional health so that appropriate help can be provided immediately. This assumes, as I discussed earlier, that there is a well-thought-out plan, with trained counselors, school psychologists, and social workers to handle the next steps in the process which might also include external agencies equipped to treat adolescent mental health disorders. The Mental Health Technology Transfer Center Network (MHTTC) has developed a general structure (see Figure 1, below) that can be used as a starting point for helping addressing students’ mental health needs.

Figure 1: A framework for supporting student mental health

Source: Mental Health Technology Transfer Center Network (MHTTC) (2020). Supporting student mental health: Resources to prepare educators. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Retrieved from: Supporting Student Mental Health: Resources to Prepare Educators | Mental Health Technology Transfer Center (MHTTC) Network (mhttcnetwork.org)

The good news is that, throughout history, human biology, with the help of science, starting with the Scientific Revolution era, has always figured out a way to adapt to social disruption and instability that caused neurobiological transformations in human beings. The coronavirus is no exception. As disruptive and life-altering as this pandemic has been, historical evidence suggests that we will come out stronger. As schools are microcosms of society, academic instruction must be protected while we simultaneously address students’ mental health needs directly resulting from Covid-19. This, in my view, should also entail educator socio-emotional/psychological support because everyone has been affected, one way or the other, by the pandemic. Research tells us that preemptive recognition and identification, coupled with timely intervention that have been carefully crafted, including trained professionals and community healthcare providers, can have the types of positive outcomes we yearn.

References

Andrews, A., McCabe, M., & Wideman-Johnston, T. (2014). Mental health issues in the schools: Are educators prepared? The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education, and Practice, 9(4), 261-272. doi:10.1108/JMHTEP-11-2013-0034

Becker, M.S. (2021). Educators are key in protecting student mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brookings Institution. Brown Center Chalkboard. Retrieved from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2021/02/24/educators-are-key-in-protecting-student-mental-health-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82, 405-432.

EdWeek Research Center (2021). Student mental health during the pandemic: Educator and teen perspectives. Retrieved from: https://fs24.formsite.com/edweek/images/EdWeek_Research_Center-Student_Mental_Health_During_the_Pandemic.pdf

Ekornes, S. (2017). Teacher stress related to student mental health promotion: The match between perceived demands and competence to help students with mental health problems. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(3), 333-21. doi:10.1080/00313831.2016.1147068

Froese-Germain, B., & Riel, R. (2012). Understanding teachers' perspectives on student mental health: Findings from a national survey. Ottawa: Canadian Teachers Federation. Retrieved from https://www.ctf-fce.ca/Research-Library/StudentMentalHealthReport.pdf

Graham, A., Phelps, R., Maddison, C., & Fitzgerald, R. (2011). Supporting children's mental health in schools: Teacher views. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 17(4), 479-496. doi:10.1080/13540602.2011.580525

Harris, N.B. (2019). The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity. UK: Mariner Books.

Hoover, S., Lever, N., Sachdev, N., Bravo, N., Schlitt, J., Acosta Price, O., Sheriff, L. & Cashman, J. (2019). Advancing comprehensive school mental health: Guidance from the field. Baltimore, MD: National Center for School Mental Health. University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/cumulative-cases

Kidger, J., Gunnell, D., Biddle, L., Campbell, R., & Donovan, J. (2010). Part and parcel of teaching? Secondary school staff’s views on supporting student emotional health and well-being. British Educational Research Journal, 36(6), 919–935. doi:10.1080/01411920903249308

Knightsmith, P., Treasure, J., & Schmidt, U. (2013). Spotting and supporting eating disorders in school: Recommendations from school staff. Health Education Research, 28(6), 1004-1013. doi:10.1093/her/cyt080

Koller, J. R., & Bertel, J. M. (2006). Responding to today’s mental health needs of children, families and schools: Revisiting the preservice training and preparation of school-based personnel. Education and Treatment of Children, 29(2), 197–217.

Mental Health America. (2016). Position statement 41: Early identification of mental health issues in young people. Retrieved from https://www.mhanational.org/issues/position-statement-41-early-identifi….

Mental Health Technology Transfer Center Network (MHTTC) (2020). Supporting student mental health: Resources to prepare educators. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Retrieved from: Supporting Student Mental Health: Resources to Prepare Educators | Mental Health Technology Transfer Center (MHTTC) Network (mhttcnetwork.org)

Opendak, M., Offit, L., Monari, P., Schoenfeld, T.J., Sonti, A.N., Cameron, H.A, Gould, E. (2016). . Lasting adaptations in social behavior produced by social disruption and inhibition of adult neurogenesis. Journal of Neuroscience, 36(26): 7027 DOI: Retrieved from: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4435-15.2016 https://www.jneurosci.org/content/36/26/7027

Phillippo, K. L., & Kelly, M. S. (2014). On the fault line: A qualitative exploration of high school teachers’ involvement with student mental health issues. School Mental Health, 6(3), 184-200. doi:10.1007/s12310-013-9113-5

Reinke, W. M., Stormont, M., Herman, K. C., Puri, R., & Goel, N. (2011). Supporting children's mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. School Psychology Quarterly, 26(1), 1.

Rothi, D. M., Leavey, G., & Best, R. (2008). On the front line: Teachers as active observers of pupils’ mental health. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(5), 1217–1231. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2007.09.011

-------------------------------------------------------------

Mental health resources for educators and students

ED COVID-19 HANDBOOK Roadmap to Reopening Safely and Meeting All Students’ Needs. Volume 2 • 2021. Available at: https://www2.ed.gov/documents/coronavirus/reopening-2.pdf

Supporting Student Mental Health: Resources to Prepare Educators: https://mhttcnetwork.org/centers/mhttc-network-coordinating-office/supporting-student-mental-health