I’ve always appreciated Andy Smarick’s efforts to create a new vision for urban school districts, but his recent piece about the importance of data in education strikes an especially resonant chord. Understanding the context where we preach our policy “scripture” is pivotal if our ultimate goal is to improve children’s opportunities. EdBuild is very much rooted in the notion that student lives play out in this context, not in theory.

That said, statistics can be dangerous. All of Andy’s examples are relevant, on-target, and interesting. The percentage of school spending on salaries and benefits, the gap between men and women receiving college degrees, and the demographic changes sweeping across our nation’s schools are all critical information for policymakers and advocates alike. But stopping at an average can often lead to overgeneralization. For instance, using numbers from the Department of Education, he states, “State and local governments provide the same amount of funding for schools—gone are the days when local districts were on their own financially. Today, property taxes produce a majority of funding in only a few states…”

While this is true at the aggregate level, it’s misleading. Without further context, the statement distorts a very stark picture of what’s happening in our public education systems more locally.

Take my home state of New Jersey. Newark Public Schools generate just 17 percent of their funding from local taxes, and Jersey City—my current town of residence—can raise 18 percent. In these districts, the state is picking up the majority of the cost of educating children because the local municipalities can’t generate enough to fully fund their schools. Alternatively, my relatively well-to-do hometown of Bridgewater has enough local wealth to pay 84 percent of the cost of their schools from local property taxes; Cherry Hill—the tony suburb that all of my friends wanted to live in—covers 91 percent of their costs from local taxes. If you were to average these four together, you’d find that the reported local tax contribution in New Jersey is 51 percent. But that doesn’t paint a very thorough picture of what’s actually happening on the ground. Across the country, some districts are dependent on the whims of their state governments, and others are just fine with what their resident populations can provide from their own wealth. The reason for this is clear: Affluent areas have been extremely effective in walling off their property wealth for their own schools, letting the state pick up the tab for their neighbors’ children. New Jersey is affluent enough overall that it’s capable of making up that difference, but many states don’t have the resources (or the political will) to equalize funding in the same way, leaving poor districts far behind.

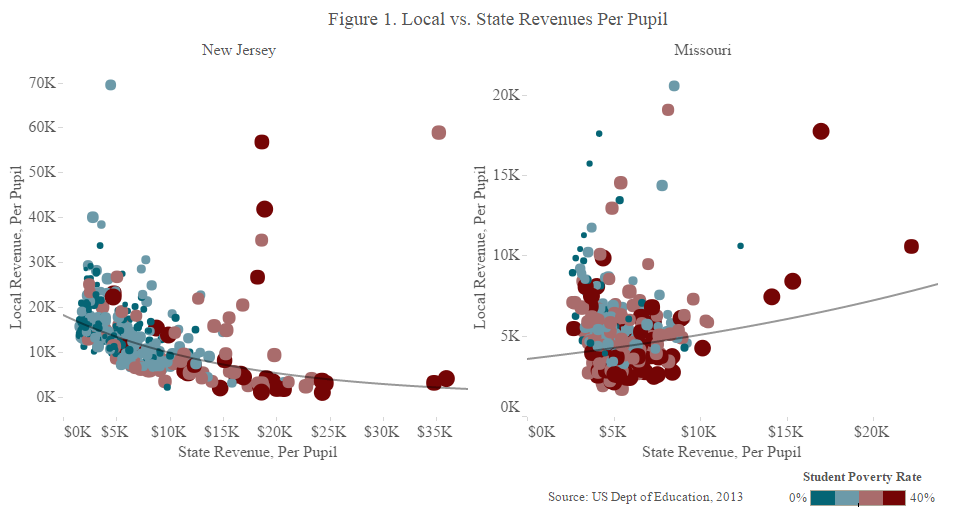

For instance, compare New Jersey to Missouri. Figure 1 provides a side-by-side comparison, with local revenue on the y-axis and state revenue on the x-axis. While New Jersey provides more funding to districts with lower local revenue, Missouri provides more funding to districts with greater local revenue—and in case you believe that high-poverty districts are raising large amounts of local funding, the size and color of each bubble represent poverty rates. The highest-poverty districts in Missouri trend toward the bottom of the scatter, meaning they receive less local revenue per pupil but not necessarily more state dollars. Whereas in New Jersey, high-poverty districts trend toward the lower-right side, with low local but high state revenue.

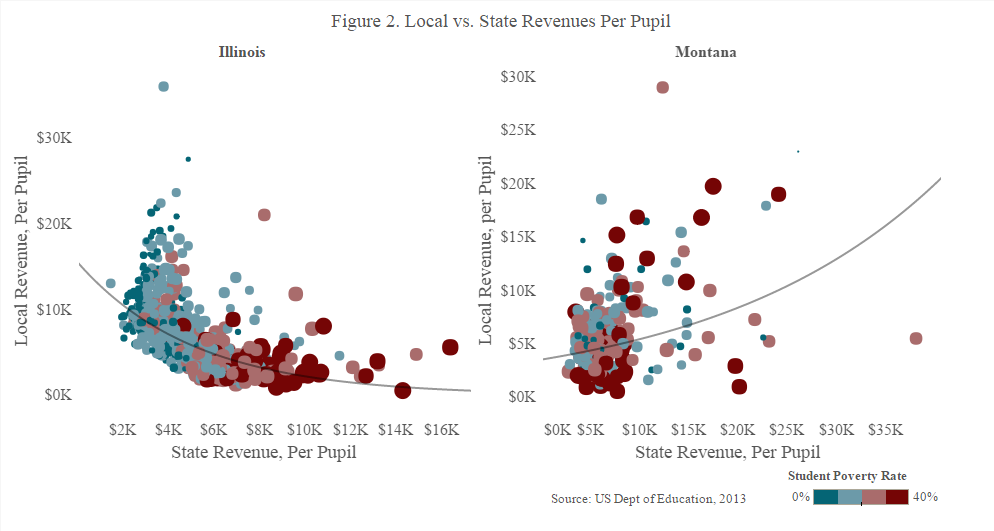

Averages necessitate this sort of nuance. If state and local governments are supporting education at about the same funding levels, then progressive areas have to be counterbalanced by regressive: a Missouri for every New Jersey, a Montana for every Illinois, (Figure 2) and so forth. In this case, balance does not illuminate newfound equality. It outlines the shadow of systemic inequities.

Ultimately, this is the danger of education experts having a common foundation of knowledge based on only a shallow excavation of the data. A little information can be a dangerous thing, especially when combined with good intentions and the power to create change.

Rebecca Sibilia is the founder and CEO of EdBuild, a nonprofit focused on bringing common sense to our school funding system. Prior to starting EdBuild, Rebecca served as the chief operating officer and VP for fiscal strategy at StudentsFirst and held several high-level public finance positions in the District of Columbia.