This post originally appeared in a slightly different form at Psychology Today.

There is much wrong with American kindergartens—but the Common Core State Standards are not to blame. If interpreted correctly, the Common Core standards for literacy enable us to help enhance the kindergarten experience for all kindergarten children—from the underprepared to the most gifted and advanced. Here’s how the literacy standards can be interpreted to support reading and writing in kindergarten without harming any child.

A recent report by early childhood experts amplified by the Washington Post says that “requiring kindergartners to read—as Common Core does”—may harm children. The position paper, written by early childhood experts, states that many kindergartners aren’t developmentally ready to read. While well intended, both the media report and the recommendations of the early childhood experts lead us down the wrong path.

What’s the Harm in Common Core Kindergarten Literacy Standards?

Both the Washington Post report and the research report, which was issued jointly by the Defending the Early Years and the Alliance for Childhood organizations, call for the kindergarten Common Core State Standards (CCSS) to be withdrawn. Six of the literacy standards are deemed “harmful.” In this post, I un-complicate the six CCSS kindergarten standards and ask you to decide if each of the standards would be an appropriate expectation for your child in kindergarten. You may find that the standards are reasonable and desirable once they are demystified and interpreted correctly.

Not only are my interpretations based on cognitive development and socio-cultural theory, but also on a tried and true research-based strategy for monitoring beginning reading and writing development called Phase Observation. Phase Observation has been used successfully by teachers in Montessori kindergartens, in play-based kindergartens, and even in so-called “academic” kindergartens. It is not geared to a particular pedagogy or ideology. Rather, it hews to the idea that each child’s thinking and likely brain-reading architecture goes through five phases in learning to read and write, from non-reading to proficient end-of-first-grade reading and writing. Observable and quantifiable reading and writing skills are byproducts of each phase. The first three phases applied below align with expectations in kindergarten. Two higher phases align with first grade.

To set the context, the Reading Instruction in Kindergarten report reminds us how CCSS standards are supposed to work with a quote from the Common Core website:

Students advancing through the grades are expected to meet each year’s grade-specific standards and retain or further develop skills and understandings mastered in preceding grades.

Let’s consider each “harmful” kindergarten standards one by one; I’ll interpret it for you, and you decide if it’s appropriate for your child.

***

Fluency: CCSS.EDA-LITERACY.RF.K.4

CCSS language: Read emergent-reader texts with purpose and understanding.

In other words: At the end of kindergarten, a child is expected to have a repertoire of Level-C or D easy emergent-reader texts that he or she enjoys reading fluently, purposefully, and with understanding. These books are often mastered through memory reading in guided reading lessons for kindergarten developed by New Zealand educator Don Holdaway’s classic “for-with-by model” to simulate “lap reading” with babies and toddlers. This teaching method has been used successfully in kindergartens for decades. The emergent-reader text is first modeled by the teacher for the students, then joyfully read over and over with the students until eventually the easy book is independently read by the students with great joy and confidence.

This memory reading jump-start to later reading proficiency is like using training wheels for riding a bike. Kindergartners who engage in this activity generally point to the words as they read, demonstrating both essential reading skills such as left-to-right orientation of print as well as book concepts like learning what a title is, what an author is, and how one can learn new things with books. The kindergartner who reads this emergent-reader text with purpose and understanding is confident and motivated and, just as importantly, feels like a reader. She gets in the flow and says, “I can read!”

Learning to read emergent-reading texts with purpose and understanding in kindergarten has nothing to do with “long hours of drill and worksheets,” as was erroneously reported in the Reading Instruction in Kindergarten report. Well-trained kindergarten teachers don’t subject children to hours of drill and stacks of worksheets. Your child should not be engaging in that kind of instruction.

Would this kind of reading be harmful to your child?

***

Phonics and word recognition: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RF.K.3.B

CCSS language: Associate the long and short sounds with common spellings (graphemes) for the five major vowels.

In other words: At the end of kindergarten, a child is expected to read on sight some high-frequency long and short vowel words. The kind of text reading that would fit this expectation would be something like the adorable Level-B picture book Cat on the Mat, by Brian Wildsmith. It’s a fun read about animal friends who one by one dare to sit on a mat with a cat until the elephant comes and it’s much too crowded. “Sssppstt!” goes the cat, and everyone scrambles away. The picture book has a six-word sentence on most pages and is engagingly illustrated; kids love it.

A byproduct of reading it is that kids learn a few sight words with the all-important Consonant-Vowel-Consonant (CVC) short vowel pattern, as in cat, sat, and mat; it’s arguably the most critical phonics pattern to be mastered for successfully negotiating the beginning reading of English. In best-practice classrooms, children may choose from hundreds of titles of books like this, including engaging fiction and delightful informational texts.

After a well-trained teacher sees that the kindergartner has mastered a repertoire of these Level-B books, she will move him into Level-C and sometimes D books such as Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat. Most of us remember the first lines: “The sun did not shine. It was too wet to play. So we sat in the house all that cold, cold, wet day.” These opening sentences, though simple, expose the reader to multiple CVC short-vowel phonics patterns and word recognition, moving well toward first-grade reading levels. The rhyming pattern books are only one of the choices children may choose from in kindergarten. Titles that meet both of these first two standards include hundreds of books in different genres: Cool Off, I Love Bugs, In the City, My Dream, Playhouse for Monster, Roll Over!, and Spots, Feathers and Curly Tails all give a wide sample of the range of topics.

Would this kind of reading be harmful to your child?

***

Print concepts: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RF.K.1.D

CCSS language: Recognize and name all upper- and lowercase letters of the alphabet.

In other words: At the end of kindergarten, a child is expected to have begun constructing meaningful emergent-writer texts independently. A byproduct of everyday writing is that, at the end of kindergarten, the kids will recognize and name all upper- and lowercase letters of the alphabet—but in reality, they go way beyond that. Kindergarten pieces are largely done in invented spellings sprinkled with a growing repertoire of high-frequency words that the kindergartner learns to spell correctly.

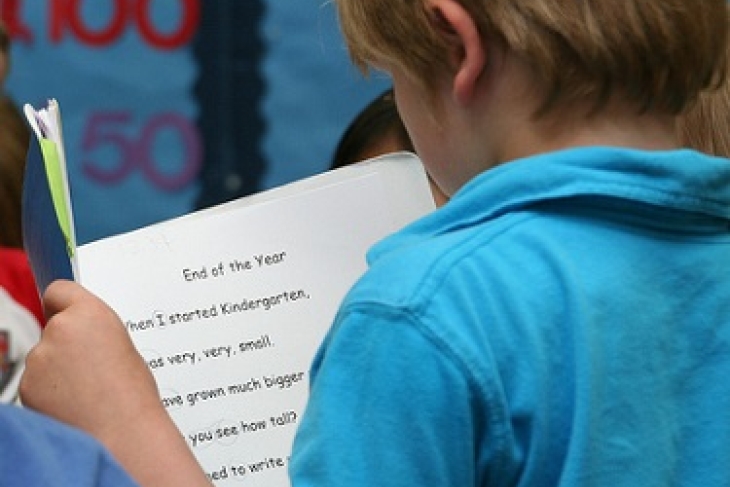

Under the coaching of a well-trained teacher, children in kindergarten write every day. They choose their own topics and enjoy creating extended and deliberate textual compositions in increasing textual complexity. They can think, draw, and write narratives or observations from real life experiences. Eventually, drawings and writing in kindergarten might advance from “one-word stories” such as “Tweety,” a story one kindergartner wrote about his pet parrot, to “phrase stories” such as “My Motor Boat,” and eventually to little pieces expressing real or imagined experiences, information, or opinions. By the end of the year, these pieces may grow in length to compositions of six or more sentences about whatever kindergartners are interested in.

Well-trained kindergarten teachers help kids “publish” the “kid writing” by transcribing it into conventional Standard English, which kindergartners love reading back over and over. This reinforces and strengthens their reading brain circuitry. As kids notice and try to figure out spelling, grammatical usage, punctuation, and capitalization—and teachers scaffold and give them positive feedback—they learn letters and gain exposure to many conventional Standard English skills

Would this kind of reading be harmful to your child?

***

Integration of knowledge and ideas: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.K.9

CCSS language: With prompting and support, identify basic similarities in the differences between two texts on the same topic. (e.g., in illustrations, descriptions, or procedures).

In other words: At the end of kindergarten, a child is expected to be able to identify basic similarities in the differences between two texts, such as Cat on the Mat by Brian Wildsmith and The Cat in the Hat by Dr. Seuss. Kindergartens compare and contrast the pictures and stories, then tell you which one they like best and why. One kindergartner told me that both books had a cat, but he liked the Dr. Seuss book best because it reminded him of a time he had to find something to do on a rainy day. (“Like I could read my favorite books!” he said.)

Would this kind of reading be harmful to your child?

***

Research to build and present knowledge: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.K.7

CCSS language: Participate in shared research and writing projects.

In other words: At the end of kindergarten, a child is expected to have participated in many shared research and writing projects. For example, your child might plant seeds and keep records of tending them by drawing and labeling. He might watch and record in pictures and labels the cycle of tadpoles turning into frogs, the metamorphosis of butterflies, the hatching of baby chicks, or the goings-on in an ant farm. She might tend to a live bunny in the classroom and report on the everyday happenings with the pet. She might draw pictures and report in writing on how the class guinea pig looks, feels, smells, eats, and sounds. She might visit parks and streams and draw pictures and write about the experience; she could research the kinds of trees or flowers that were found in the parks and take field notes with sketches and labels. Much of this work may be done at kindergarten play-centers; the research is reported in phase-appropriate writing with increasing textual complexity, as described in the standards detailed above.

Would this kind of reading be harmful to your child?

Vocabulary Acquisition and Use: CCSS.ELA.LITERACY.W.K.4.B

CCSS language: Use the most frequently occurring inflections and affixes (e.g., -ed, -s, re-, un-, pre-, -ful, -less) as to cue the meaning of an unknown word.

In other words: At the end of kindergarten, your child should acquire many new words and use them in his or her speech. Most of us who spend a lot of time listening and talking to kindergarteners know that they communicate quite effectively using the inflections and affixes listed above in everyday vernacular, regardless of their dialects. They use them for varying verb tenses and making words plural (though, depending on their dialect, they may not yet use all with conventional Standard English usage and spelling). We make reasonable accommodations for bilingual children. At the end of kindergarten, and with the exception of some bilinguals who have had too little experience with English, most can use word parts such as the ones listed above in their speech. They express what they are thankful for at Thanksgiving, how to unscrew the jar of peanut butter, recap the apple juice; alternatively, they can show you that the art-center floor is spotless after they cleaned it up. At the end of kindergarten, they can still tell you about their experiences in preschool, if they were fortunate enough to attend one.

Should your child be expected to use this kind of rigorous English vocabulary?

Do any of the above standards make you feel that “we have hurried the reading process,” as reported in the Reading Instruction in Kindergarten report?

Problems with American Kindergarten and How to Fix It

My intent is not to denigrate this report, its authors, or their affiliated organizations. These are wonderful groups, and the report brings many serious problems in American kindergarten to light. I must agree with the following bulleted items detailed in the publication, which I have encountered all across America:

- Some children are having harmful experiences in kindergarten.

- Districts in affluent communities spend about twice as much per student as the lowest-spending districts.

- Some districts are causing problems by shoving a first-grade curriculum into kindergarten.

- Children without high-quality preschool and without experience with literacy at home enter kindergarten not ready for success with reading.

- Children in low-quality kindergartens should not be required to meet the needs of low-quality schools for standardized tests.

- There is too much standardized testing in kindergarten.

- Kindergarten report cards are problematic in some districts.

- There is not enough formative assessment during the learning process by well-trained teachers in kindergarten.

- Many kindergarten teachers are not well prepared to teach English language arts.

I do not dismiss any of these grievances. I’m simply saying that the Common Core State Standards are not the problem, and rewriting or abandoning the standards is not the solution. We don’t need to start over from scratch; the current CCSS standards can be interpreted cogently and specifically and can help to provide expanded opportunity for all kindergartners. The adoption of the standards do not “falsely imply that having children achieve these standards will overcome the impact of poverty on development and learning,” as stated in the report. They only spotlight a problem: Poor children in low-quality schools will never move toward inclusive prosperity unless they learn to read and write. The journey starts in high-quality preschools and kindergarten, unless parents start little ones on the journey at home.

If you find these interpretations of Common Core standards for kindergarten helpful, email the link or copy the post and give it to your child’s principal and kindergarten teacher.

J. Richard Gentry earned his bachelor's degree from the University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill in elementary education and his Ph.D. in reading education from the University of Virginia. He is an education consultant and author of books for parents and teachers, including Raising Confident Readers: How to Teach Your Child to Read and Write—From Baby to Age 7.