At this week’s meeting of the state board of education, board members accepted Ohio Department of Education (ODE) recommendations on cut scores that will designate roughly 60–70 percent of Ohio students as proficient (based on the 2014–15 administration of PARCC). While this represents a decline of about fifteen percentage points from previous years’ proficiency rates, it isn’t the large adjustment needed to align with a “college-and-career-ready” definition of proficiency. In fact, this new policy will maintain, albeit in a less dramatic way than before, the “proficiency illusion”—the misleading practice of calling “proficient” a large number of students who aren’t on-track for success in college or career.

The table below displays the test data for several grades and subjects that were shared at the state board meeting. The second column displays the percentage of Ohio students expected to be proficient or above—in the “proficient,” “accelerated,” or “advanced” achievement levels. The third column shows the percentage of Ohio students in just the “accelerated” or “advanced” categories—pupils whose achievement, according to PARCC, matches college- and-career-ready expectations. The fourth column shows Ohio’s NAEP proficiency, the best domestic gauge of the fraction of students who are meeting rigorous academic benchmarks.

Under these cut scores, Ohio will report proficiency rates that continue to overstate the proportion of Ohio students who are on track. This is crucial because proficiency is widely reported in the media, leading many to believe that students are generally doing just fine. On the other hand, the accelerated-plus rate isn’t likely to be emphasized in the media or reported to parents, even though it is the college- and career-ready level defined by PARCC. This rate is also more in line with NAEP results (certainly in ELA, though a bit harsh in math).

Source: Ohio Department of Education Note: The PARCC results are preliminary and based only on students taking computer-based exams. Approximately three in five students took online exams.

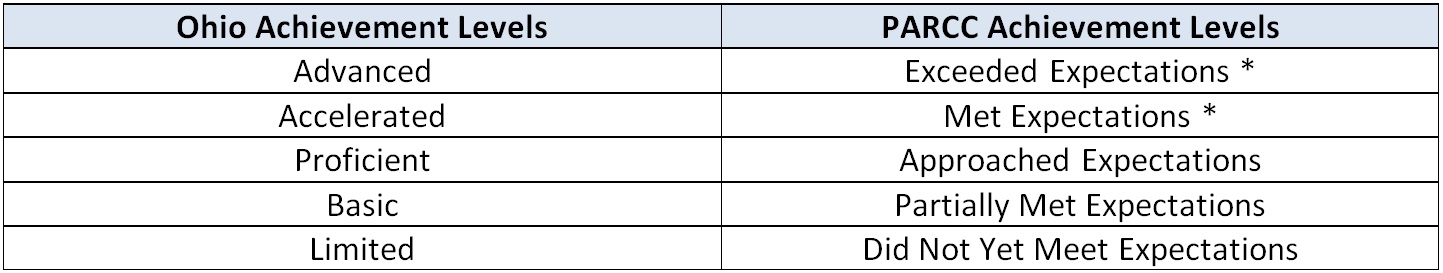

Before casting stones at the State Board or ODE for “lowering standards,” bear in mind that they were constrained by state law, which prescribes five achievement levels—each of which has its designation enshrined in law (ORC 3301.0710). The table below displays a crosswalk between Ohio’s and PARCC’s achievement levels. (The asterisk denotes the PARCC achievement level that corresponds to being on-track for college or career.) As you can see, under present law, there was no simple way the state board or ODE could have aligned the state’s proficient category with the college-and career-ready achievement levels set by PARCC.

The state board has made its call regarding 2014–15 cut scores. But what can the state do moving forward to end the proficiency illusion? Here are three ideas that policymakers should consider, keeping in mind that some of them may take legislative action to implement:

1.) Eliminate the accelerated designation and replace it with proficient; then, replace proficient with another achievement-level identifier, such as “approaching.” In this scenario, the achievement levels would be: advanced, proficient, approaching, basic, limited.

This proposal would ratchet up the meaning of “proficiency” by moving it to the second-highest achievement category—one that could be the threshold for college and career readiness. Indeed, an arrangement such as this would have enabled the state to align its proficient category with PARCC’s college- and career-ready performance levels. While Ohio won’t administer PARCC moving forward, this structure could be adopted when the state shifts to ODE/AIR-designed exams.

2.) Retire the current achievement-level descriptors (e.g., proficient, basic) and move to a “level” or “star” system. The state could define that Level 4 and Level 5, for example, indicate college and career readiness. This idea would allow for the creation of a clearly recognizable benchmark without the legacy of “proficient.” In essence, this would represent a fresh start for communicating student achievement to parents and the public.

3.) Make crystal clear which achievement level equates to meeting the college- and career-ready targets. The Ohio Department of Education, for example, should ensure that schools send home test score reports that plainly tell parents whether their children are on the college-and-career track. (For the 2014–15 year, it would be students designated at or above the accelerated level.) Of course, this suggestion applies to any performance-level structure, including the one that the state board approved this week. Worth considering as a template is this exemplary student test-score report.

As for the 2014–15 test results, proficiency won’t have much to do with college and career readiness. That’s disappointing news, as it contradicts Ohio’s stated goal of transitioning to higher standards. Moving forward, state policymakers should stop dancing around this issue and give the information needed on whether students are meeting benchmarks that set them on the surest track for success in their later lives. The rest of the nation is moving in that direction, and so should the Buckeye State.