Once upon a time, there was a small village on the edge of a river. The people there were good, and life in the village was good. One day a villager noticed a baby floating down the river. The villager quickly swam out to save the baby from drowning. The next day this same villager noticed two babies in the river. He called for help, and both babies were rescued from the swift waters. And the following day four babies were seen caught in the turbulent current. And then eight, then more, and then still more! The villagers organized themselves quickly, setting up watchtowers and training teams of swimmers who could resist the swift waters and rescue babies. Rescue squads were soon working twenty-four hours a day. And each day the number of helpless babies floating down the river increased. The villagers organized themselves efficiently. The rescue squads were now snatching many children each day. Though not all the babies, now very numerous, could be saved, the villagers felt they were doing well to save as many as they could each day. Indeed, the village priest blessed them in their good work. And life in the village continued on that basis.

—Christopher Cerf, former superintendent of public schools in Newark, New Jersey.

***

For those of us who work in the “small village” of K–12 schools, this river parable symbolizes the turbulent waters our youngest students must navigate every day. And it surfaces an uncomfortable truth—rarely confessed—that largely explains the grindingly slow progress of education reform and the withering fight against entrenched child poverty.

The overwhelmed “rescue squads” capture our valiant but tragically insufficient struggle to effectively educate the more than four million children who annually enroll in kindergarten, far too many of whom enter school a year or more behind their classmates in academic and social-emotional skills.

On November 14, in his keynote address at the inaugural School Readiness Forum, Chris Cerf shared this allegory to describe the ongoing challenge faced by K–12 educators. After his speech, I had the honor of moderating a panel he was on, along with Shael Polakow-Suransky, the president of Bank Street College of Education; Barbara Reisman, a senior advisor of the Maher Charitable Foundation; and Sarah Walzer, the CEO of the Parent-Child Home Program.

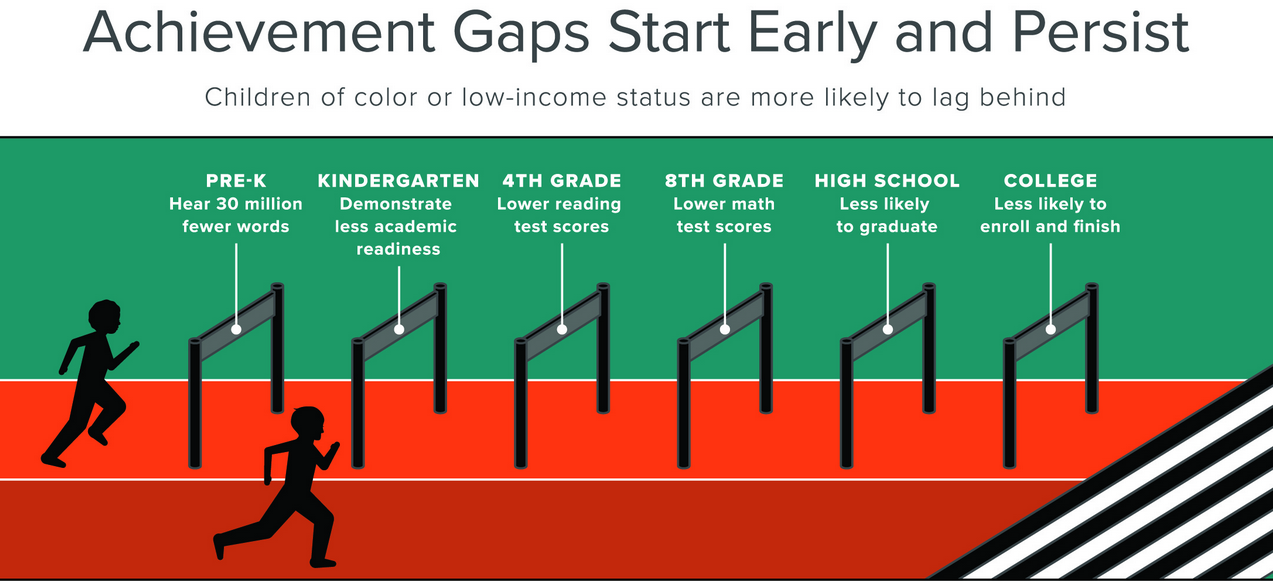

“Many have heard about the 30-million-word gap—the difference in the number of words heard by low-income children and those heard by well-off children before they even enter kindergarten. That gap is devastating, but in too many cases it is only the beginning of a gap that begins in the birth-to-four-years period and continues to grow as children enter school and move through classrooms unprepared to be there,” said Sarah Walzer on the panel.

Indeed, a consensus is growing among educators that the deficits a child experiences during ages zero to three are inextricably linked to almost inevitable adverse, long-term harm to their well-being later in adulthood. Even non-academic institutions like the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneaopolis have generated evidence-based infographics like the one below to depict the reliably predictable and negative lifelong effects of trauma before the age of five.

SOURCE: The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

As Shael Polakow-Suransky argued in an op-ed for the New York Daily News, “Missing this small but vital window of opportunity leads to intense efforts later in our schools to try and support students who are struggling. Most of the achievement gap between rich and poor children is already evident by kindergarten, and it stubbornly persists as students enter and complete middle and high school.”

For leaders in K–12 public education, this recurring theme of helplessness to reverse adverse early childhood experiences is an achingly bitter pill to swallow. No one wants to believe that our efforts are futile. Yet despite decades of extraordinary efforts by incredibly talented and committed K–12 educators, and more than $600 billion spent annually, the sobering reality in most places seems to be that, absent a transformation in how children are nurtured in utero and in the cradle, “the inequality that begins before kindergarten lasts a lifetime,” as Heather Long said in the Washington Post.

But we must fight to ensure that early hardships do not necessarily have to determine destiny. Though the river parable sadly analogizes the perpetual and often unwinnable game of academic catch-up for under-resourced children who enter kindergarten far behind, the story’s final passage commands us to seek out the root causes of the crisis of too many “floating babies”:

One day the villagers noticed a young man running northward along the bank. They shouted, “Where are you going? We need you to help with the rescue.” He responded, “I am going upstream to find the son of a gun who is throwing these kids into the river!”

***

The promising focus of the aforementioned School Readiness Forum was to explore new ideas and practical ways to “head upstream” to prevent the K–12 achievement gap.

As an example, the non-profit charter management organization I lead, Public Prep, announced a first-of-its-kind partnership with the Parent-Child Home Program that Sarah Walzer leads. Through the partnership, younger siblings of current students at our four Boys Prep and Girls Prep Bronx campuses will receive almost one hundred thirty-minute home visits before they receive automatic lottery preference into PrePrep, our universal preschool program that begins with four-year-olds.

For two years—two times each week—a trained, community-based early-learning specialist will bring the family a new high-quality book or educational toy as a gift. Using the book or toy, the specialist will work with the child and the child’s caregiver in their native language to model reading and conversation and do activities designed to stimulate parent-child interaction and promote the development of the verbal, cognitive, and social-emotional skills that are critical for children’s school readiness and long-term success.

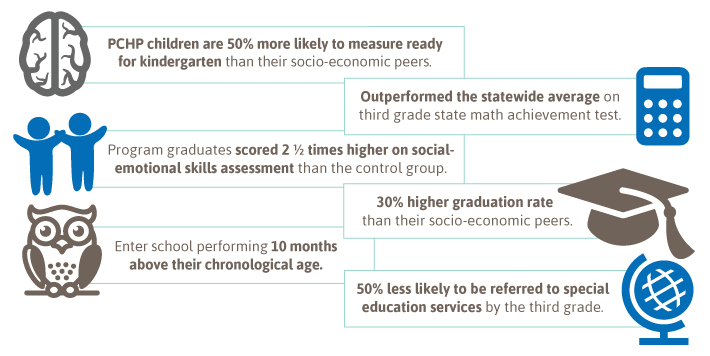

For more than fifty years, Parent-Child Home Program has demonstrated that its research-based home visiting model has consistently and profoundly improved children’s academic performance, as this infographic demonstrates:

SOURCE: Parent-Child Home Program

This home-visiting partnership epitomizes Public Prep’s philosophy that educators have to start helping students early in their lives, and do so with the end in mind. It has the potential to be a game-changer. By beginning interventions as young as eighteen-months-old, it can significantly alter students’ trajectories.

Yet despite this promise, the likelihood of home visiting becoming a systemic solution is dampened by the fact that the United States currently spends just one-twentieth of its annual K–12 budget on early-childhood education and care.

This ought to change, especially considering recent scientific studies that suggest we must urgently reverse the effects of adverse childhood experiences. Conducted in the emerging field of human neuroscience, one study found that the brain is not structurally complete at birth, and that a baby’s pre-natal and early familial engagement can either strengthen or weaken brain architecture, which provides the foundation for future learning, behavior, and health. And the Centers for Disease Control, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Harvard University Center on the Developing Child all report that toxic stress within the first three years of life is an identified risk factor that significantly elevates the odds that a child will have one or more delays in their cognitive, language, or emotional development.

This new research expands the knowledge base that trauma created or exacerbated by being raised in a fragile family, intertwined with child poverty, dramatically increases the probability that a child will suffer consequences well into adulthood.

It is why leaders in K–12 education reform must deploy a two-generation bookend approach. First, seek out supports for our youngest scholars before they enter kindergarten to increase the chances of healthy infant brain development. Second, throughout students' K–12 education, when volatile periods often compromise the development of their adolescent brains, proactively intervene to emphasize self-regulation and impulse control. We must exercise our intellectual, moral, and practical responsibility to empower teenagers to break the cycle by helping them develop attitudes and behaviors more likely to prevent the creation of fragile families in the first place.

Young people are coming of age at a time when our nation is in the midst of a five-decade explosion in the rate of multiple, non-marital births—across all race and all states, especially to women and men at or under the age of twenty-four—that is seismically shifting family structures in a way that puts children at risk.

Despite these cultural norms, beginning optimally with students entering eighth grade, we must help the next generation develop a framework for making life choices as they embark upon the next twelve years of their lives in high school, college, and young adulthood—during which they’ll make myriad critical decisions that will have lifelong consequences, positive or negative.

***

In Chris Cerf’s aforementioned speech, he shared that, after thirty years of working as a history teacher, deputy chancellor, district superintendent, and state commissioner, he had come to a conclusion: Rather than call the work to improve K–12 outcomes “education reform,” a more appropriate title would be “education repair,” given the armada of “rescue squads” our “village” has had to deploy to remediate very young children.

But we don’t have to be in the business of repair. In a different era, Frederick Douglass once noted, “It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.”

On the front end, we know that effective early interventions like home visiting can improve school readiness and reduce chronic exposure to toxic stress that inhibits brain development. And on the back end we can help teenagers entering adulthood reframe how they think about the timing of their own family formation to give themselves—and their future children—the best chance of success.

See you upstream.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.