Everyone is right to laud the impressive work of Senate HELP Committee Chairman Lamar Alexander and ranking member Patty Murray in producing a strong bipartisan bill to update the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB). But it has a significant flaw that needs mending before it becomes law, and it might be up to House Republicans to do the fixing.

The problem, in a nutshell, is that it puts enormous pressure on the states to set utopian goals. That, in turn, will result in most schools being declared failures (and/or create pressure for states to water down their standards), which is exactly what happened under NCLB.

At issue is a true dilemma for policymakers: There seems to be an irresistible urge in education to set aspirational goals. There’s nothing wrong with that, per se—stirring, “shoot for the moon” rhetoric can be motivational and galvanize action. But as Rick Hess and Checker Finn have explained, when it’s time to create accountability systems, policymakers must sober up. If they set unrealistic, unreachable goals, the people working in the system will grow cynical and disillusioned—the opposite of motivated.

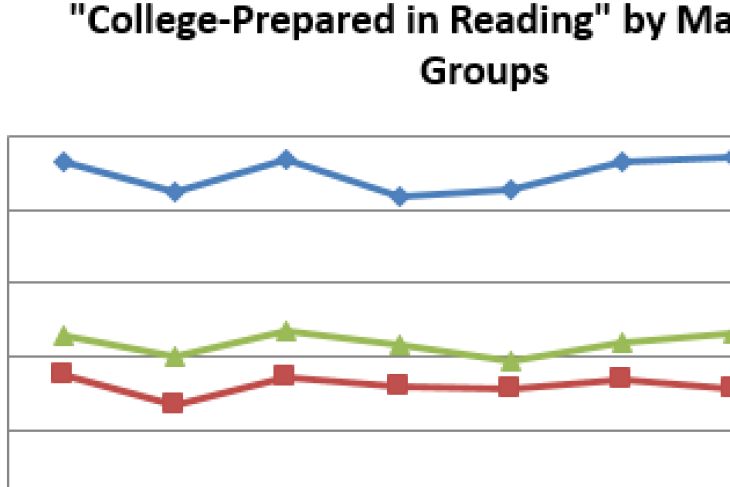

Senator Alexander’s discussion draft bill got this balance right. (So does the House Republicans’ Student Success Act.) It started with the moonshot: State accountability systems will “ensure that all students graduate from high school prepared for postsecondary education or the workforce without the need for remediation.” That’s a fantastic aspiration. But it’s not going to happen, not in the 5–10 years until (let’s hope!) Congress renews the Elementary and Secondary Education act again. I am quite confident about this because, as Checker and I reported last week, the college preparedness rate hasn’t broken the 40 percent mark in at least twenty years. Unless you assume that “workforce preparedness” will require dramatically lower skills in reading and math, it strains credulity to believe that universal “college or career readiness” is attainable anytime soon. We’ll be doing well, over the life of this reauthorization, to get half the high school graduates there. Two-thirds would be a miracle.

But the ambitious, aspirational language of Alexander’s original bill (and the House Republicans’ bill) is OK because it doesn’t require state accountability systems to literally expect all students to reach college or career readiness. Instead, it pivots, simply requiring states to annually measure “academic achievement of all public school students in the State towards meeting the challenging State academic standards in mathematics and reading or language arts, which may include measures of student academic growth to such standards and any other valid and reliable academic indicators related to student achievement.”

Sadly, the compromise bill is not so wise. If I’m reading it right, it requires states to pledge that they will get all of their students to college or career readiness and build those expectations into their accountability systems. Specifically, states must annually establish “State-designed goals for all students and each of the categories of the students in the State that take into account the progress necessary for all students and each of the categories of students to graduate from high school prepared for postsecondary education or the workforce without the need for postsecondary remediation, that include, at a minimum, academic achievement, which may include student growth, on the State assessments,” along with graduation rates.

Now, to be sure, the bill doesn’t establish a federally prescribed timeline like NCLB did (100 percent proficiency by 2014), and it takes great pains to block the secretary of education from micromanaging the “state-designed goals” themselves. If a state wants to, it can decide that its goal is to reach universal college and career readiness by 2050 and design an accountability system that will measure schools’ progress against that leisurely pace. Yet we can all imagine what would happen if states chose that reasonable and realistic path—groups like Education Trust would excoriate them.

These issues will be particularly sensitive when it comes to setting goals for African American and Latino students, as their college preparedness rates are especially distant from the moonshot goals.

So Senator Murray and her allies would drive states into a box canyon. They will face three bad choices. First: acknowledge publicly that not all of their students will be college- or career-ready anytime soon, especially their poor and minority students. Second: aim for universal college or career readiness in the near future and label most of their schools as failures. Or third: redefine “college- or career-ready” to mean “minimal proficiency in reading and math.” This would flush all of the Common Core-related (and other) efforts to raise standards right down the drain.

One would hope that state policymakers would act like grownups and choose option number one. But option two—and especially option three—will be much more politically palatable.

There’s little doubt that the introduction of mandatory state goals reflects a big concession by Chairman Alexander to Senator Murray and her supporters in the civil rights and business communities. It’s not as bad as a federally prescribed timeline would be, and it shouldn’t be a reason for Republican Senators to halt the reauthorization process. As Checker wrote last week, bipartisanship means “everybody holding their noses over provisions they don’t like, even while agreeing that the totality is an improvement over current law.” This bill deserves to be reported out of committee.

Still, it needs to be fixed—either on the Senate floor or in a future conference committee. House Republicans: Get your talking points ready.