You don’t have to be a diehard liberal to believe that it’s nuts to wait until kids—especially poor kids—are five years old to start their formal education. We know that many children arrive in kindergarten with major gaps in knowledge, vocabulary, and social skills. We know that first-rate preschools can make a big difference on the readiness front. And we know from the work of Richard Wenning and others that even those K–12 schools that are helping poor kids make significant progress aren’t fully catching them up to their more affluent peers. Six hours a day spread over thirteen years isn’t enough. Indeed, as our colleague Chester Finn calculated years ago, that amount of schooling adds up to just 9 percent of a person’s life on this planet by the age of eighteen. We need to start earlier and go faster.

But the challenge in pre-K, as in K–12 education, is one of quality at scale. As much as preschool education makes sense—as much as it should help kids get off to an even start, if not a “head start”—the actual experience has been consistently disappointing. Quality is uneven. Money is spread thin. Teachers are poorly educated. And benefits quickly fade. There are exceptions, of course, but it’s no easier to run a great high-poverty preschool than to run a great high-poverty elementary school. It’s possible, but rare.

So if policymakers want to ramp up high-quality preschool programs, where should they turn? To the big and often dysfunctional urban school districts that struggle so mightily to get the job done for K–12 students? To Head Start centers, which continue to resist a focus on academic preparation and hire mostly low-wage, poorly trained instructors? To for-profit preschool providers? (We don’t hear many liberals proposing that.)

What the Left and Right can get behind are pre-K programs that deliver the goods: nonprofit institutions that prepare young children, and especially low-income children, for the rigors of education today. What could be a more ideal solution, both politically and substantively, than high-quality charter schools? Why on earth, then, is it so difficult for America’s high-impact, “no-excuses” charter schools—committed as they are to helping poor kids succeed in K–12 education and proceed to good colleges and worthwhile careers—to participate in pre-K programs? Who wouldn’t want the KIPPs or Achievement Firsts or Uncommon Schools of the world to be able to get started with three-year olds and work their edu-charm as early as possible?

Commonsensical though it may be, however, the preschool and charter school movements have grown up parallel to one another, rarely intersecting as often or effectively as they could. Because of the siloed nature of policymaking and finance, charter schools in many states are greatly restricted (and in some places even prohibited) from offering preschool. That’s what we found in our new, pathbreaking study, Pre-K and Charter Schools: Where State Policies Create Barriers to Collaboration.

To conduct the analysis, we approached early childhood and charter school expert Sara Mead at Bellwether Education Partners. Sara is an education policy veteran, having once directed the New America Foundation’s Early Education Initiative and spent time at Education Sector and the Progressive Policy Institute. She now serves on the District of Columbia Public Charter School Board. Sara’s colleague Ashley LiBetti Mitchel, a savvy public policy analyst in her own right, co-designed and co-authored the study. (The research was made possible through the generous support of the Joyce Foundation, the Walton Family Foundation, the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, and our sister organization, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation.)

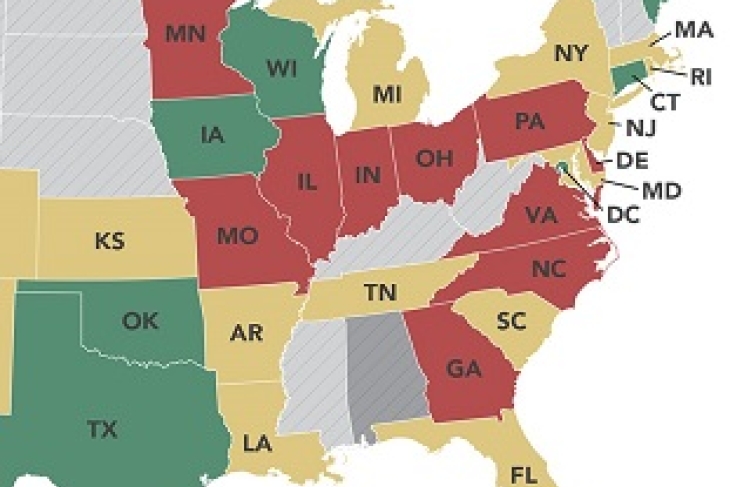

Among Mead and Mitchel’s most dismaying findings: Charter schools cannot offer state-funded pre-K in the thirteen states that lack either charter laws or state pre-K programs. In nine other cases, state law is interpreted as prohibiting charters from offering pre-K. Where the practice is permitted, charters still face all sorts of barriers, including meager pre-K funding (and/or district monopoly of funds), woefully small programs, and restrictions on new providers. Charter schools are often barred from automatically enrolling pre-K students into their kindergarten programs without first subjecting them to a lottery.

In other words, charter schools get the short end of the stick. Again.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. As this report proposes, we can do much to demolish the barriers that prevent the charter and pre-K sectors from working together. But that requires us to understand how two programs with very different origins can be brought together. New York Times columnist David Brooks gets it. Last November, he posited that “a collaborative president might jam a mostly Democratic idea, federally financed preschool, and a mostly Republican idea, charter schools, into one proposal.” This horse trade—more support for charter schools in exchange for more support for preschool— might represent a bipartisan way forward. Why not charter preschools? Why not charter elementary schools that start at age three?

Policymakers, this is low-hanging fruit. Why not pick it?