Editor’s note: This is an edition of “Advance,” a newsletter from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute written by Brandon Wright, our Editorial Director, and published every other week. Its purpose is to monitor the progress of gifted education in America, including legal and legislative developments, policy and leadership changes, emerging research, grassroots efforts, and more. You can subscribe on the Fordham Institute website and the newsletter’s Substack.

This week brings initial data from the 2022 Nation’s Report Card—what my colleague Checker Finn has fittingly called “the little-known test that matters the most.” This first tranche will show us long-term trends for America’s nine-year-olds, giving us a snapshot of their academic progress and math and reading skills before and after the Covid pandemic. Later in the fall, we’ll get new reading and math scores for fourth and eighth graders nationwide, as well as broken down by state and twenty-six large urban school districts.

As these releases loom, it’s worth reflecting on recent, pre-pandemic trends, as well as how the United States compares to its competitors. This newsletter focuses on advanced education, kids reaching the high end of the achievement spectrum. Looking at these data can help us build a case for the success of these programs, be they gifted education or higher-level coursework—or gauge whether we need more of them.

We find both good and bad news. The good news is that, over the last decade, the U.S. was getting more students to the high end of achievement in fourth and eighth grade, especially in math. The bad news: There’s no progress in high school—and the U.S. lags behind far too many countries, sometimes by huge margins. We are, in other words, headed in the right direction, but there’s still a lot of work to be done, especially in the upper grades.

The case for advanced education is simple, has two parts, and is worth restating, for it demonstrates why efforts to better educate advanced learners are so important. The first argument is equity-based: Every student deserves educational experiences that help them reach their full potential. Some children, due to high achievement, ability, or potential, require something more than can be provided in the average classroom geared toward the average student. Schools should therefore offer distinctive and high-quality advanced programs and services for those who would benefit from them. Not to do so is an unacceptable form of discrimination.

The second argument is that the country needs these children to be highly educated to ensure its long-term competitiveness, security, and innovation. They’re the young people most apt to become tomorrow’s leaders, scientists, and inventors, and to solve our current and future critical challenges. Indeed, economists don’t agree on much, but almost all concur that a nation’s economic vitality depends heavily on the quality and productivity of its human capital and its capacity for innovation. While the cognitive skills of all citizens are important, that’s especially the case for high achievers. Using international test data, for example, economists Eric Hanushek and Ludger Woessmann estimate that a “10 percentage point increase in the share of top-performing students” within a country “is associated with 1.3 percentage points higher annual growth” of that country’s economy, as measured in per-capita GDP.

Back to math scores. Considerable research suggests that “math skills better predict future earners and other economic outcomes than other skills learned in high school.” Math also lends itself best to international comparisons because there is wide consensus about what students should learn in this subject, and because its concepts are the same regardless of the language of instruction. Math scores are therefore my focus here, particularly the percentage of students reaching the highest levels on national and international exams. (This is a different metric than one used in two recent analyses by the National Assessment Governing Board and my colleague Mike Petrilli, which show a divergence in the pre-pandemic decade between low and high achievers, using scale scores at the 10th, 25th, 75th, and 90th percentiles.)

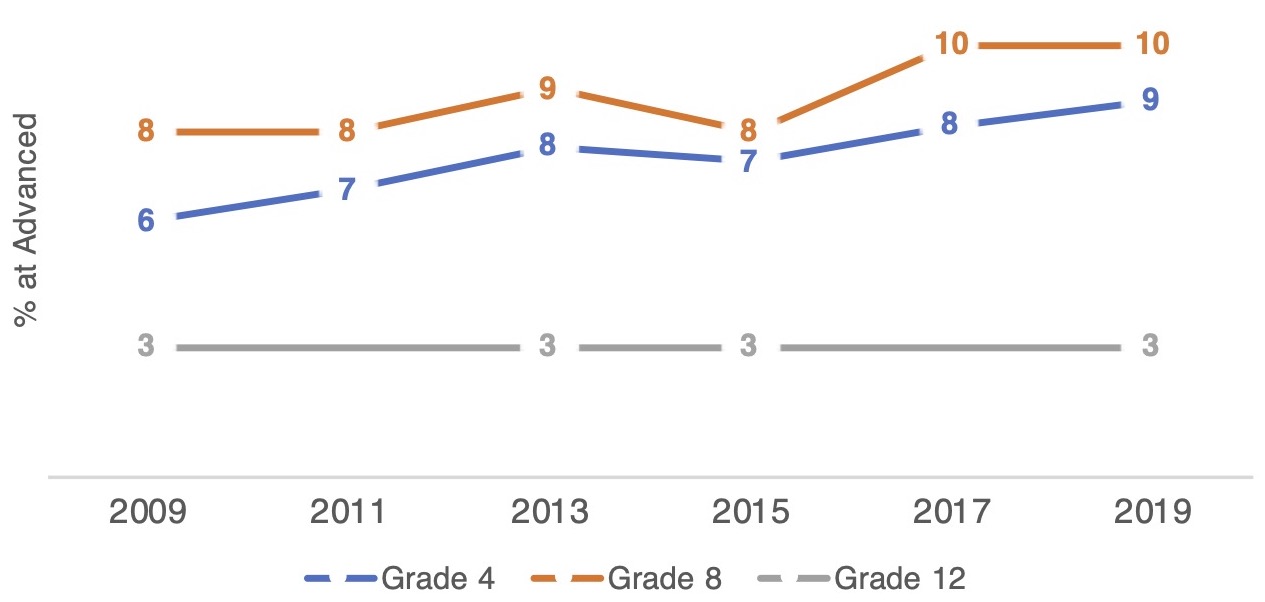

Figure 1 shows the percentage of students at or above “NAEP Advanced,” the test’s top achievement level, from 2009 to 2019 in grades four, eight, and twelve. The increases in the earlier grades are large, statistically significant, and encouraging, with grade four seeing a 50 percent jump, from 6 to 9 percent scoring at the Advanced level, and grade 8 rising 25 percent from 8 to 10 percent Advanced. (Reading also saw statistically significant rises in these grades during this time, but only by 1 percentage point.) Twelfth grade, however, is another story. Just 3 percent of test-takers reached NAEP’s top level in 2009—a figure that, sadly, didn’t change in 2013, 2015, or 2019.

Figure 1. Percentage of students at or above NAEP advanced level, by grade, 2009–19.

Turning to comparisons with other nations, it’s clear that the U.S. isn’t doing well at the upper end in relation to our competitor countries.

Consider, for instance, such well-known gauges as the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), in which dozens of countries participate. PISA tests fifteen-year-olds in math, science, and reading, and organizes its scores into seven levels, from 0 to 6, with high scorers generally being those who reach level 5 or 6. TIMMS assesses fourth and eighth graders in math and science and splits its scores into five levels, with a high achiever judged as one who reaches at least 625 on the relevant scales.

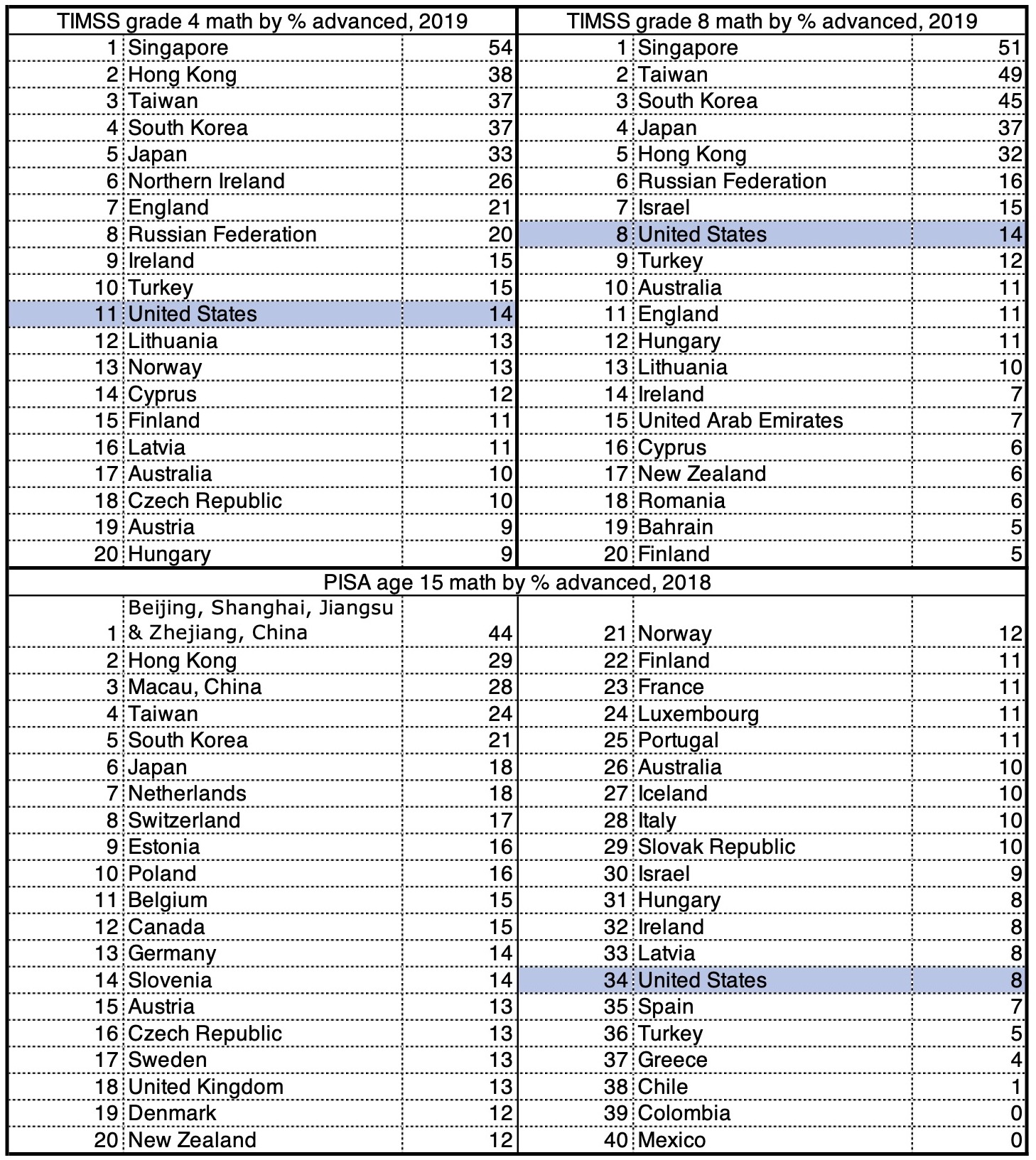

Using these cutoffs, Table 1 shows the percentage of advanced test-takers for a selection of top-scoring countries who participated in the most recent math assessments. It also shows how the United States compares.

Table 1. Percentage of students scoring at the advanced level in math on TIMSS 2019 and PISA 2018, by country

In the TIMSS results, we see the U.S. ranking eleventh in grade four and eighth in grade eight. In both, America landed behind Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, and Russia. Worse, the top-performing countries have two, three, and in the case of Singapore, almost four times the proportion of advanced students as does the U.S. The only silver lining is that many of these countries are small. America’s vast scale means that we have a decently large number of high achievers in raw numbers.

PISA paints an even worse picture for high-achieving high school students in the U.S., mirroring our dismal NAEP results for twelfth-graders. Rankings include all members of the OECD that took the assessment, plus Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and a quartet of Chinese cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang). That’s a total of forty jurisdictions. The United States comes in thirty-fourth, behind all participants in Asia and every participant in Europe except Spain, Turkey, and Greece.

But recall the good news: Over the last pre-pandemic decade, the U.S. was getting more of its students to the highest level of achievement in fourth and eighth grade math. And what Table 1 doesn’t show is trends. So here’s one that offers some hope: In 2019, 14 percent of U.S. eighth graders reached TIMSS’s top math level. Eight years earlier it was just 7 percent.

So perhaps this fall, when PISA next tests students around the globe, America’s rank will jump. Or not, considering America’s broad learning losses during the pandemic—losses that were exacerbated by, among other things, the country’s too-cautious approach to school closures, hybrid learning, and masking. “Over past two years,” reported the Economist earlier this year, “America’s children have missed more time in the classroom than those in most of the rich world.” So it’s possible, maybe even likely, that any comparative gains we’d made before Covid hit were erased by bad policy decisions at federal, state, and local levels.

Either way, all these data suggest that math learning for America’s advanced students was headed in the right direction before the pandemic. And perhaps, that the gifted programs that exist in 68 percent of U.S. primary and middle schools are doing something right. These are things to celebrate—at least guardedly, as we wait for new scores. What’s also clear is that there’s much work ahead, and that maintaining and accelerating advanced education in our schools in the best interest of America’s students, American prosperity, and American security.

—

QUOTE OF NOTE

“When we explore how exposure to tracking correlates with student mobility in the achievement distribution, we find positive effects on high-achieving students with no negative effects on low-achieving students...”

—Kate Antonovics, Sandra E. Black, Julie Berry Cullen, and Akiva Yonah Meiselman, “Patterns, Determinants, and Consequences of Ability Tracking: Evidence from Texas Public Schools,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 30370, Abstract, August 2022

—

THREE RECENT STUDIES TO STUDY

“Patterns, Determinants, and Consequences of Ability Tracking: Evidence from Texas Public Schools,” by Kate Antonovics, Sandra E. Black, Julie Berry Cullen, and Akiva Yonah Meiselman, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 30370, August 2022

“We use detailed administrative data from Texas to estimate the extent of tracking within schools for grades 4 through 8 over the years 2011-2019. We find substantial tracking; tracking within schools overwhelms any sorting by ability that takes place across schools. The most important determinant of tracking is heterogeneity in student ability, and schools operationalize tracking through the classification of students into categories such as gifted and disabled and curricular differentiation... Finally, when we explore how exposure to tracking correlates with student mobility in the achievement distribution, we find positive effects on high-achieving students with no negative effects on low-achieving students….”

“Parenting with eyes wide open: Young gifted children, early entry and social isolation,” by Mimi Wellisch, Gifted Child International, Volume 37, Issue 1, 2021

“This case study outlines the challenges of eight Australian mothers with intellectually gifted preschoolers... It was found that early entry met the needs of children whose parents chose this acceleration option and that the preschoolers who missed out because of intervention by their educators did not fare so well. Findings also indicated an urgent need for the inclusion of compulsory early childhood giftedness courses for Australian pre-service educators and an equally urgent need for professional development courses about giftedness for educators already working in early childhood services.”

“Finding Talent Among Elementary English Learners: A Validity Study of the HOPE Teacher Rating Scale,” by Nielsen Pereira, Gifted Child Quarterly, Volume 65, Issue 2, 2021

“The purpose of this study was to investigate the validity of the HOPE Scale for identifying gifted English language learners (ELs) and how classroom and English as a second language (ESL) teacher HOPE Scale scores differ… Results also indicate that the rating patterns of classroom and ESL teachers were different and that the HOPE Scale does not yield valid data when used by ESL teachers. Caution is recommended when using the HOPE Scale and other teacher rating scales to compare ELs to EP students. The importance of invariance testing before using an instrument with a population that is different from the one(s) for which the instrument was developed is discussed.”

—

WRITING WORTH READING

“Gifted education and equity are not at odds,” Wall Street Journal, Ellen Winner, August 29, 2022

“Frisco ISD’s grading policies hurt high achievers like me,” Dallas Morning News, Vaishnavi Josyula, August 29, 2022

“Shakeup at Manhattan high school appeases affluent families whose kids didn’t get into elite schools, say parents,” New York Daily News, Michael Elsen-Rooney, August 29, 2022

“What national test scores tell us about American education before the pandemic,” Thomas B. Fordham Institute, Michael J. Petrilli, August 31, 2022

“Osceola [Florida] School District receives highly-competitive $2.6M grant for gifted studies among under-represented student segments,” Osceola News Gazette, Ken Jackson, August 28, 2022

“It’s never too early—or late—to identify gifted students,” K–12 Dive, Lauren Barack, August 17, 2022

“Gifted summer programs skew white and wealthy. Not Baltimore’s—and it’s free,” The 74, Asher Lehrer-Small August 17, 2022

“Philly public schools drop writing sample, add standardized tests back to selective admissions process,” WHYY, Aubri Juhasz, August 17, 2022